The quality of our citizenship correlates very neatly with the global distribution of wealth. Courtesy of Shutterstock.

Why do we still cling to citizenship?

Certainly, it’s not required to protect your rights. We live in a world of human rights, where slavery is outlawed, gay people can marry, and thinking for yourself (rather than obedience to authority) is valued. So why, in societies based on the ideal of equal human worth, does citizenship still exist?

Citizenship is typically justified with romantic notions—self-determination, democracy, preservation of values. But at its core, citizenship is little more than a certain legal status within a certain legal system. By defining its rights and privileges as bound to a particular state, citizenship itself violates our cherished idea of equal human worth. Instead, citizenship is most effective at upholding caste systems both within and among nations.

In most cases, citizenship is granted more or less at random, based on where your family was from, or where you were raised. Public authorities grant citizenship; the actual citizen typically has no participation in the decision. Once granted, citizenship cannot be refused—or changed before obtaining some other citizenship, without the risk of becoming a “stateless” person, deprived of the rights of citizenship anywhere in the world.

Citizenship was created to legally proclaim equality among the haves and have-nots. It did not eliminate socioeconomic inequality; it merely explained it away through the incomplete promise of “one person one vote.” This made extracting obedience from the population easier and drove nationalism. Today, even the most awful political systems boast glorified citizenships.

For most of its history, citizenship has been useful for a very ugly reason. Citizenship allows us to ignore the basic tenets of the enlightenment—the presumption that humans are equal—without real argument. It is enough to say “She is not a citizen” to justify excluding someone from rights, entitlements, and respect.

Citizenship, thus, can divide as much as it unites. We see that in the U.S. with DACA kids, the Dreamers, who are threatened with being thrown out of their home country because they lack citizenship. And America is not alone. Citizenship divides not only people within a nation, but confers unequal status based on the privileged status of some nations over others. Think of those who possess the all-entitling super-citizenships of nations of the global north, versus the limitations against people who come from former colonies—it’s clear that the status quo of citizenship is racist.

Racism is just one of the core building blocks of citizenship; sexism is another, as citizenship was routinely denied to women as well as minorities until well into the 20th century.

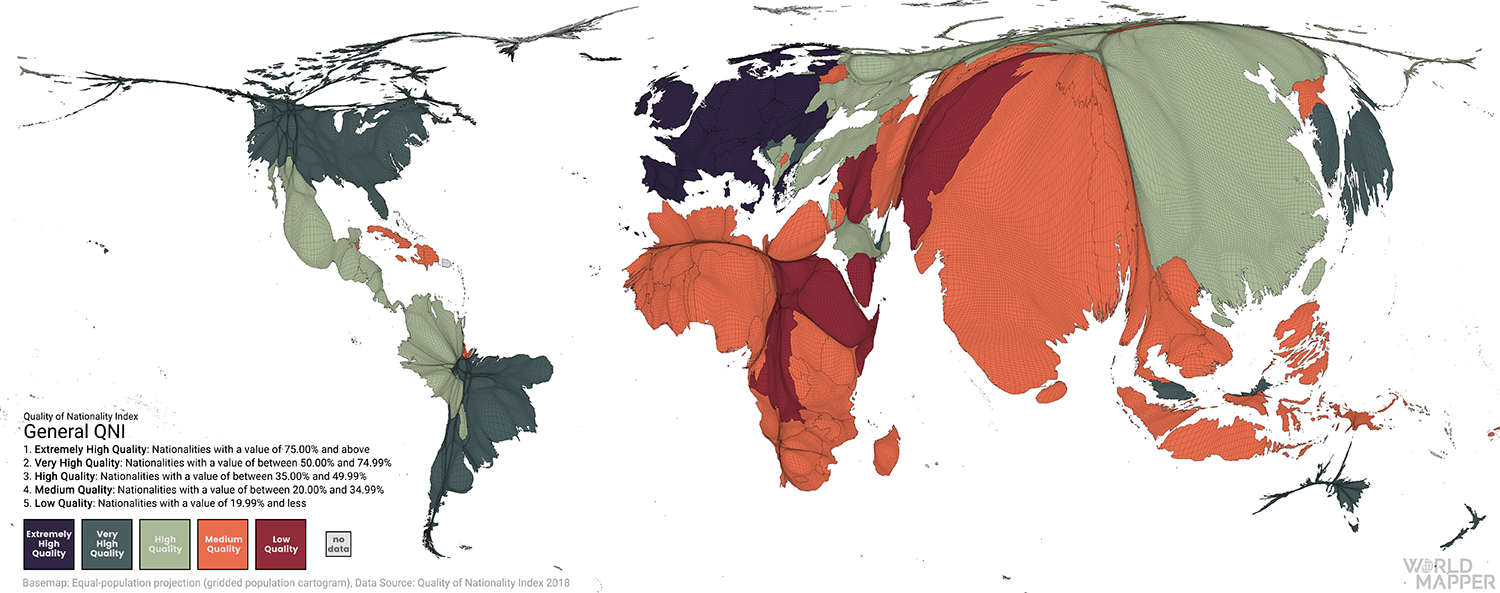

This map is the world rescaled so that the relative sizes of the countries express the relative sizes of their populations. The map is colored to show the “Quality of Nationality”—that is the power conferred by citizenship—in each place, with darker colors indicating higher quality citizenship. Courtesy of B.Hennig and D. Ballas.

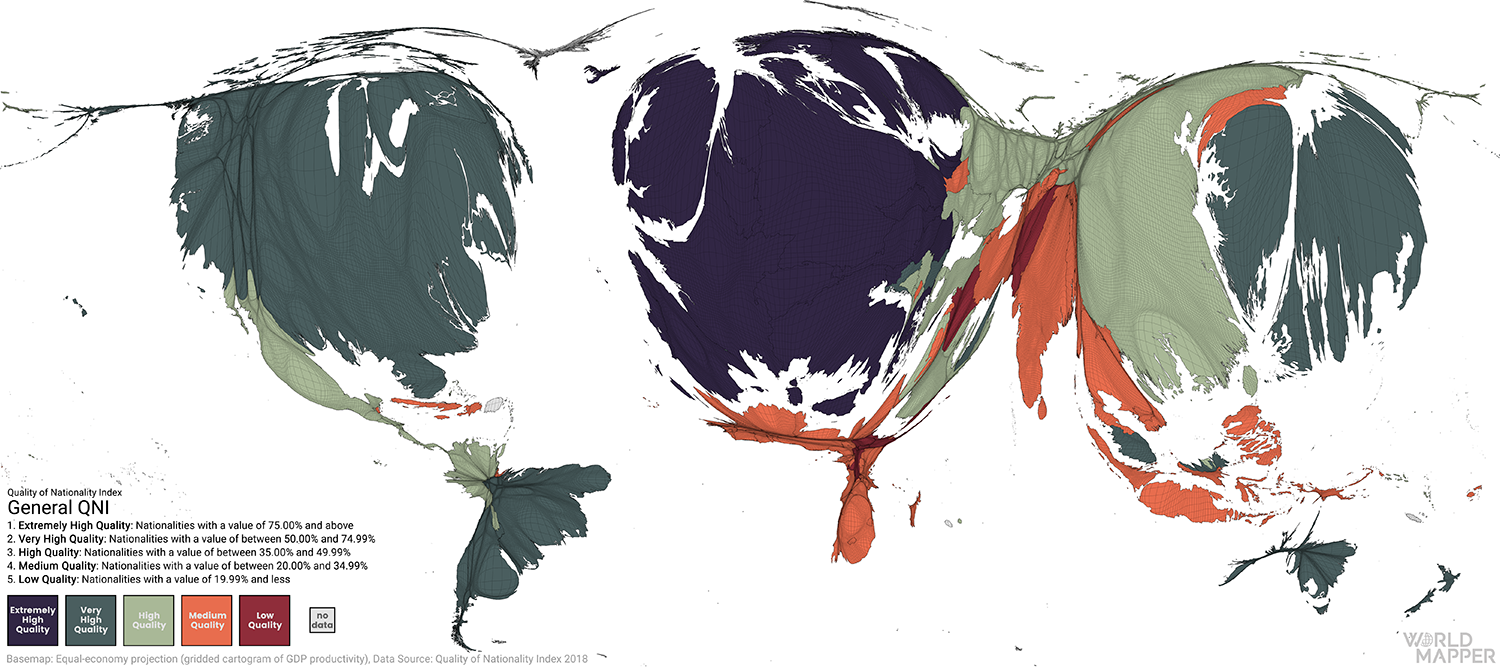

This map is the world rescaled so that the relative sizes of the country express the relative sizes of the GDP of the countries. This map, like Map 1, is colored to show the “Quality of Nationality”—that is the power conferred by citizenship—in each place, with darker colors indicating higher quality citizenship. When you compare maps, note how closely higher GDP correlates with high quality citizenship. Courtesy of B.Hennig and D. Ballas.

Citizenship is at a crossroads now: the dominant narrative that the global equality of human beings can be assured within states is in reality eroding. Different citizenships are not equal, and the allocation of citizenship rights worldwide is neither logical nor clear.

At the macro level, citizenship enables the perpetuation of rigid pre-modern caste structures. The son of an American is an American, and the son of a brahman is a brahman. We do not ask ourselves whether this is just.

To argue for citizenship at a micro level is utterly confounding and contradictory. Being a tenured professor is irrelevant to citizenship in Germany, but was crucial to securing immediate citizenship in Austria until 2008. “Being active in the diaspora” is irrelevant to Austrians, but can make you a Pole. Having a Lebanese mother is irrelevant to Lebanese citizenship, but having a Jewish mother, even without Israeli citizenship, can make you Israeli.

Examples of this disparity in the rules of citizenship are countless: what is taken for granted as best practice in one country can seem almost outrageous in another. But the contradictions should point us to the bigger problem with citizenship: there cannot be a “worse” or a “better” method of assignment to a caste. Any caste system depends on repugnant assumptions and should be intolerable, at least in modern democracies.

All citizenships are described often as equally valuable—even though this assumption is flawed. Equality of different citizenships would only work in a world where authorities could enforce standards of self-fulfillment and personal empowerment in every country. In such a world, citizenship would provide rights, not liabilities.

And in such a glorious world, citizenship would then be irrelevant.

But we live in a world where there are Pakistanis, whose citizenship is a global liability; they must hold a visa to travel to any other country, and hold no settlement rights abroad—and also Norwegians, who enjoy countless rights at home and can settle in more than 40 of the richest democracies without any formalities. In our world, citizenships do not have equal dignity. We are treated differently according to the color of our passport, and citizenship upholds random privilege. Look from Europe across the Mediterranean, or peer from the U.S. across the wall President Trump is building, and you see a world order where punishing randomness and hypocrisy reign.

The quality of our citizenship correlates very neatly with the global distribution of wealth. Most of the world’s people are losers of what prominent scholar Ayelet Shachar called ‘the birthright lottery.’ That is because they are denied the mobility and security that comes with a passport from an economically advanced nation and got their status at random. By controlling the borders between states, citizenship is the most important tool in the world to keep it that way.

Send A Letter To the Editors