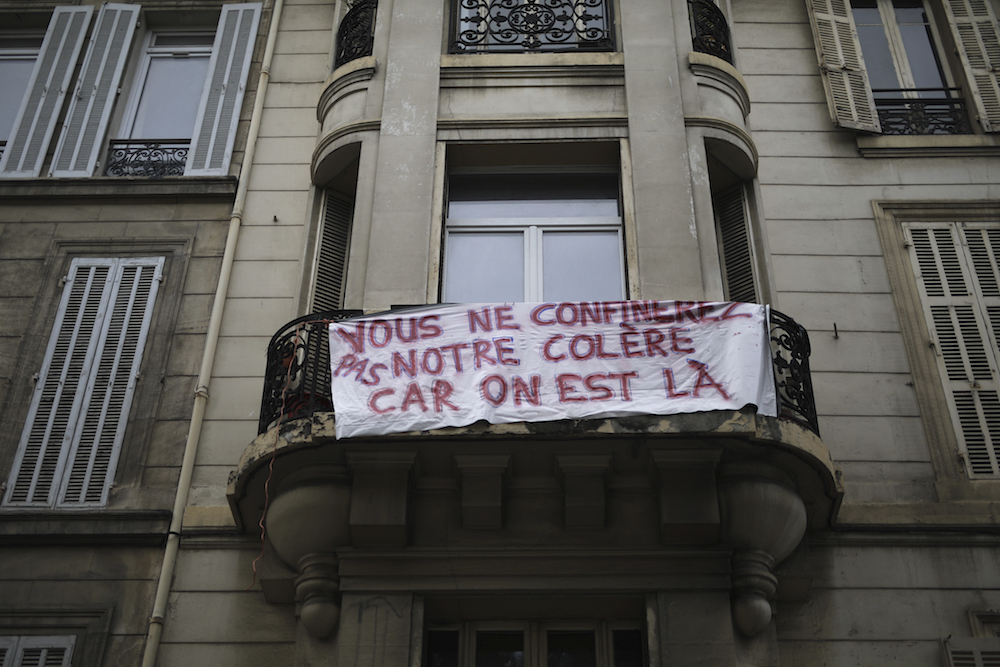

A banner reading “You will not lockdown our anger, we are there” Friday, May 1, 2020 in Marseille, France. Courtesy of Daniel Cole/Associated Press.

The COVID-19 pandemic has come at a critical historical moment. For the last two decades or so—since the collapse of the Soviet Union and communist rule in Eastern Europe—we have seen a growing erosion of liberal democracy in the West.

The reasons for this are complex and related. The disappearance of an alternative and competing political-ideological system has accelerated the accumulation of wealth and political power in ever narrower circles. This has greatly undermined the middle class, which feels, rightly, that it has been left behind. And younger generations have grown angry that, with the promise of social mobility diminishing, they will never be able to advance to the same degree as their parents.

The accumulation of wealth and power in a few hands has led to increasingly uncontrolled corruption, both economic and political. The entire social democratic system in Western Europe and the United States has come under growing strain, partly for demographic reasons (especially the aging of the population), but also because governments on both continents (France, Italy, the UK, the US, etc.) as well as in Israel, have opted to show ever less generosity toward society’s weaker elements. In the pandemic, this weakening can now be seen in the hollowed-out public health system throughout these countries.

These gradual changes in the socioeconomic infrastructure—to borrow Marxist terms—eventually came to be reflected in the cultural and political supra-structure. The resulting politics of resentment—strongly reminiscent of what has been called “the politics of cultural despair” on the eve of 1914 and during the interwar period—have given rise to populism and authoritarianism, the quest for a “strong man,” and disgust with elites that have benefited from globalization.

These changes, in turn, have produced a new type of politics—combining elements of populism and fascism for which we still have no name. We have seen such politics in Russia, Poland, Hungary, Turkey, Israel, Italy, France, potentially soon in Germany, and perhaps most importantly in the U.S.

How will the virus shift this new politics? My fear is that COVID-19 will deepen the trends that preceded it, making things much worse.

While the virus doesn’t discriminate between the rich and the poor, the affluent, with better access to health and medications, can protect themselves better. The main victims of the virus—as has always been the case in plagues (see the Black Death)—will be those of lesser means. And the disease will increase its spread precisely because the poor, the homeless, prison inmates, and low-wage workers won’t be able to shield themselves from it.

With the disease’s spread, on top of rising poverty and homelessness, will come the realization that, within the current socioeconomic structure, some lives are worth much less than others. And that gap in how we price lives will deepen, with virus-inspired unemployment and social dislocation on a scale not so different from the 1930s.

To be sure, profound crises such as the current one can lead to reform and progress. The recognition of widespread vulnerability to biological and environmental catastrophes opens the door to major changes in the ways we organize societies. Perhaps new models will address how neglect of huge swaths of populations, or critical sectors like public health, threatens us all.

But any such changes would come in the long run. Right now, mass populations, unemployed and unable to ensure their own health, may see innovations and technologies as threats rather than cures. That fearful mindset is why this crisis may lead to the triumph of the demagogues and authoritarians.

This is a moment for those who can cheat and lie their way through everything, who can claim to be the “strong men” needed to take the helm at this dark hour. There are also opportunities in this moment for powerful economic interests to accumulate even more wealth in the short-term—no matter the catastrophic long-term consequences.

Perhaps this moment may demonstrate to the world that the current Chinese system is better geared to the challenges of the present and the future than the Western model.

That does not mean that China will become the preferred political model for the West. But we may come to resemble each other, if the West experiences a rise in the authoritarianism, xenophobia, nationalism, and repression that are all too present in China.

There is no clear historical parallel, or established model, for the sort of governance that lies ahead. We are likely to experience something quite new and scary.

To avoid the worst scenarios, democracies need to recognize that they are based on the principle that sovereignty emanates from the people, not from the leaders they elect and the bureaucracies that run the system. People themselves must assert their power. Generally, in democracies, that power is expressed through elections, but because of state’s growing ability to manipulate elections, people must begin to assert themselves daily in the public sphere. People are going to have to rise up and prepare the nations for the election of a new set of leaders—women and men who will be responsible to the people and not to the corporations, the rich and the powerful.

What we can see clearly now is a generation of leaders who are using the old Roman principle of “divide and rule,” to sow division amongst and between nations. The politics of division is about turning people against each other: white against black, majority against minority, citizens against immigrants, rural against urban, uneducated against the educated, men against women. Division is based on fear: fear of those who are different, fear of the unknown, fear of disorder and destitution. These were the tools of fascism in the previous century. COVID-19, coming as it does at a time of so many other changes, offers a stage for those who practice the politics of division to do their worst.

But the way to fight this danger is to remember that politics of unity and hope has historically won over the politics of division and fear. It is the role of community, educational, and intellectual leaders to unite with their constituencies against divisive politics. And we should act now, before the narrowing window of opportunity slams shut before our eyes.

Send A Letter To the Editors