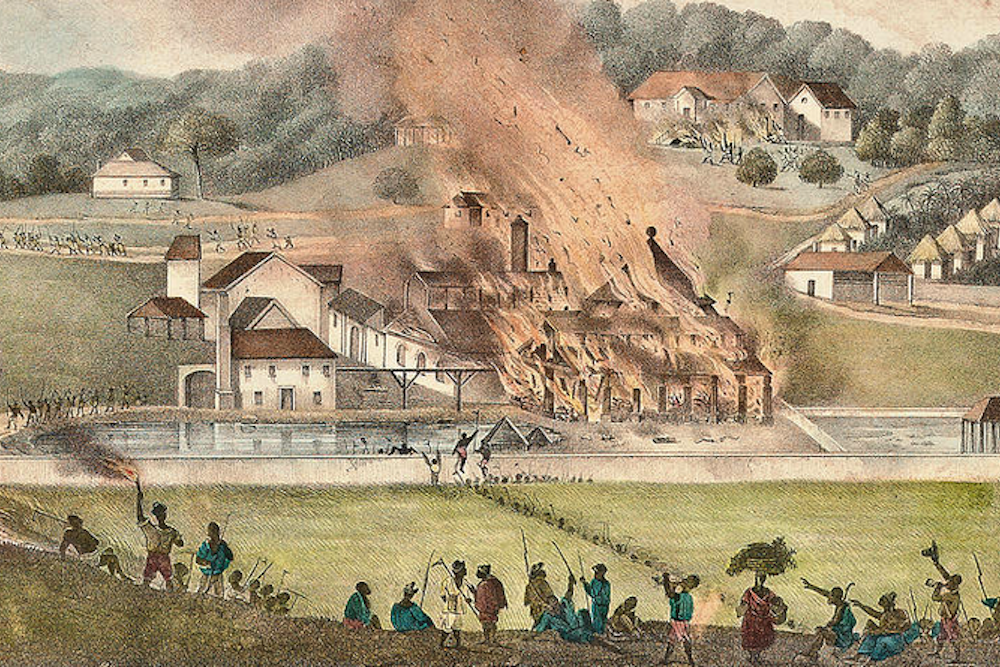

Painting by Adolphe Duperly depicting the Roehampton Estate in St. James, Jamaica, being destroyed by fire during the uprising. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In the summer of 1831, a select group of enslaved people in northwest Jamaica began murmuring to each other about “the business.”

To mention the fledgling enterprise in the presence of a white master was a ticket to torture and likely death by hanging, so everyone took precautions to swear new recruits to secrecy. With a few months, more than 60,000 enslaved people had heard about the effort, through well-wired plantation networks.

Then, on the night of December 27, 1831, “the business” opened. The first signal fires were lit in the hills above Montego Bay, and soon plantation houses went up in flames across the richest West Indian colony of the British empire. White Jamaica found itself contending with its biggest insurrection ever. It took five weeks for a British military crackdown to restore quiet.

The rebellion’s end would not be a lasting defeat. Much of the British public was already disgusted by slavery—the price of maintaining it seemed to be endless wars overseas—and after the Jamaica rebellion, political pressure built. Within 18 months of the first fire, slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire.

The rebellion, after failing, had succeeded. And not just at advancing freedom. “The Christmas Uprising” in Jamaica was a groundbreaking action and a model; its enslaved leaders anticipated the methods of later revolutionary movements—from the Irish Republican Army to Gandhi’s struggle against the British, from the French underground fight against the Nazis to the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. The story of the Jamaican revolution suggests that methods of calculated revolutionary action transcend historical periods.

In other words, the ways of resistance are timeless.

Jamaica’s enslaved population was among the most abused and powerless on the globe in 1831. Most were illiterate. Few had ever seen anything but their owner’s plantation. Their only weapons were machetes and rocks. They constantly lived on the edge of hunger and harsh punishment. Yet even in this isolated atmosphere of extreme deprivation, they developed durable strategies for a politically successful revolution.

One such strategy was nonviolence. The chief conspirator of “the business,” an enslaved Baptist deacon named Samuel Sharpe, had insisted the protest would be a peaceful sit-down strike. The plan was to simply refuse to work on the second rest day after Christmas unless masters agreed to pay striking workers half the daily wages that a free person would get for chopping sugar cane.

This simple tactic of resistance anticipated the philosophy of Mohandas Gandhi by 70 years. What Gandhi would call satyagraha, or “truth power,” forced authorities to confront and defend a central injustice, and perhaps open their own eyes to a moral blind spot. Just as Gandhi knew that British abuses would not last forever under the scrutiny of outside public opinion, Sharpe was also aware of a larger world that might sympathize with his cause.

As a traveling church deacon, he had access to the newspapers brought by cargo ships and had read about the abolitionist sentiment in Britain. His Christian beliefs were of the pacifist kind and he repeatedly told his followers not to harm anyone. Indeed, the extremely low reported death toll among whites in the uprising—just 14, when up to 500 rebels were killed or executed—speaks to the tremendous restraint and forbearance among those who had every reason to want revenge.

The Jamaican revolution also employed a simple idealism—its leaders understood that, if oppressed people were going to risk their lives, they must be given a vision of a higher purpose that could be phrased in simple terms. Samuel Sharpe used the New Testament, visiting slave villages to preach verses considered too provocative by white missionaries, in particular those that emphasized freedom in Christ. Along with scripture, Sharpe (one of the few enslaved people on the island who was literate) let his followers in on a secret: The British people across the ocean were agitating to free the enslaved, and the King of England had signed a general “free paper” that was being kept under wraps by the Jamaican sugar barons.

This last part was embroidered. William IV was an ardent defender of slavery. But the enslaved people in Jamaica still revered his name and believed him to be their friend. Sharpe’s pro-liberty message was both simple and electric. Slavery was against God’s law and the King’s will.

This messianic vision of liberty, accessible to everyone, was not dissimilar to the collectivist ideals touted 40 years later by the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, who exulted, “In Moscow from a sea of blood and flame the constellation of the revolution will rise, high and beautiful, and will become the guiding star for the good of all liberated mankind.” Martin Luther King, Jr., an admirer of Gandhi, also advanced a message of Christian love and justice that cut across racial lines, was easy to communicate, and proved difficult to refute.

In Jamaica, Sharpe, while insisting on nonviolent methods, also knew he needed a military wing. At planning meetings in fall 1831, several of Sharpe’s lieutenants agitated for a backup plan in case the strike should fail. Two of those present—Thomas Dove and Robert Gardiner—would become the fiercest fighters against the white volunteer militia once the strike had moved into a less peaceful phase. In January, they even built and staffed an impressive hilltop fortress, designed to repel incursions, called Greenwich Hill, and fought several engagements with British troops. In this, they anticipated another commonplace practice of 20th-century resistance movements: to maintain an armed underground sector operating beneath the political wing. The Palestinian Liberation Organization and Ireland’s Sinn Fein are the most well-known examples of this “arrows and olive branch” approach.

Sharpe also cultivated the enslaved “elite.” The Jamaican colonial government was surprised when it learned that the revolt’s leaders were among the most privileged of the island’s enslaved population: head drivers, head boilers, butlers, and traveling deacons like Sharpe. They were those with seemingly the least incentive to rebel because they enjoyed the most perquisites and avoided the whipping customarily dealt out to field hands. Sharpe himself told his interrogators he had always been treated kindly by his master and never beaten.

Yet the “elites” were also best positioned to recruit followers because they were trusted both by laborers on their watch and by white guardians of the sugar estates. The value of elite support is an enduring lesson of revolution. American colonial resistance to British rule was backed by Boston’s richest men. Vladimir Lenin was no peasant; he grew up in a middle-class household in Ulyanovsk, attended Kazan University and surrounded himself with fellow educated radicals.

Sharpe also used operational tactics—including small cells and safe houses—that would become de rigeur. French Resistance operatives in World War II famously kept themselves in small clusters to avoid mass arrest, and recruited only one or two people at a time, using a case officer who did not know the central command. After the war, communist insurgents used a similar strategy. But enslaved people in 1830s Jamaica had already figured it out.

Samuel Sharpe had been permitted to travel between plantations for the ostensible reason of teaching Bible lessons and leading small worship services. This he did, but he also appointed cell leaders who appointed their own small groups. Sharpe created a ritual called “taking the swear” in which new recruits would promise on the Bible to sit down after Christmas and not work. Sharpe did the first secret swearings, but from then on, his own “case officers” did the work of exponential recruitment. In this way, and within one of the most repressive societies on earth, he built a connected network of strangers that stretched 70 miles in all directions.

Sharpe’s development of safe houses was also ahead of its time. Every Jamaican plantation had a section the white ruling class called the Negro Village: a “main street” of individual houses occupied by enslaved people. Field hands typically occupied small huts, but those in senior labor roles tended to have frame houses. In these elite houses, Sharpe preached about the “business.” His top-level recruits used these houses for the most sensitive meetings, stockpiled weapons in them, and even created their own military-style uniforms: blue jackets with red sashes.

This was not unlike the system that Nelson Mandela would use in townships all across South Africa in the formative days of the African National Congress. He would appear at certain homes unexpectedly, a step ahead of the state police. “He put a number of questions to us and then gave us a briefing about what he had been doing outside the country and then discussed the tasks that lay ahead,” recalled one man who met Mandela secretly at a house in Durban in 1962.

Finally, the Jamaican rebels were astonishingly good at the secret sharing of intelligence, and they often knew about troop movements, government decrees, and even international news before their white masters heard about it. They used a sophisticated network of deck hands, house servants, traveling Bible teachers, and cargo ship stevedores to pass along messages.

A planter on the north shore once heard a critical piece of news from Kingston before the mail arrived and surmised there must have been “some unknown mode of conveying intelligence.”

The most critical piece of information of the early uprising, however, could not have been more visible: the first signal fire lit at Kensington Estate on the night of December 27, 1831. Whether Samuel Sharpe approved of it or not, the first blaze was followed almost immediately by a chain of fires lit on neighboring plantations that turned the night sky a dazzling orange and told the entire northwestern side of the island that “the business” was coming to pass at last.

The white ruling class could not help but be intimidated to the point of total confusion.

“The whole surrounding country was completely illuminated, and presented a terrible appearance, even at noon-day,” marveled a white militiaman. “When, however, the shades of night descended, and the buildings on the side of those beautiful mountains, which form the splendid panorama around Montego Bay, were burning, the spectacle was awfully grand.”

News that such a conspiracy could have been so widespread landed with explosive force in Britain. The public became convinced that prolonging the institution of slavery would only lead to further revolts and huge transatlantic military expenses. “The slaves must be sooner or later set at freedom,” editorialized the Morning Advertiser in London, “whether it be or whether it be not for their benefit, and the sooner that proper steps are taken for this purpose, so much the better.”

Within 18 months, William IV gave his reluctant royal assent to the Slave Emancipation Act of 1833. Samuel Sharpe died on the gallows before he saw it come to pass. But the revolutionary methods of “the business” had been victorious against the most powerful government in the world, and more than 800,000 people were set free as a result.

Send A Letter To the Editors