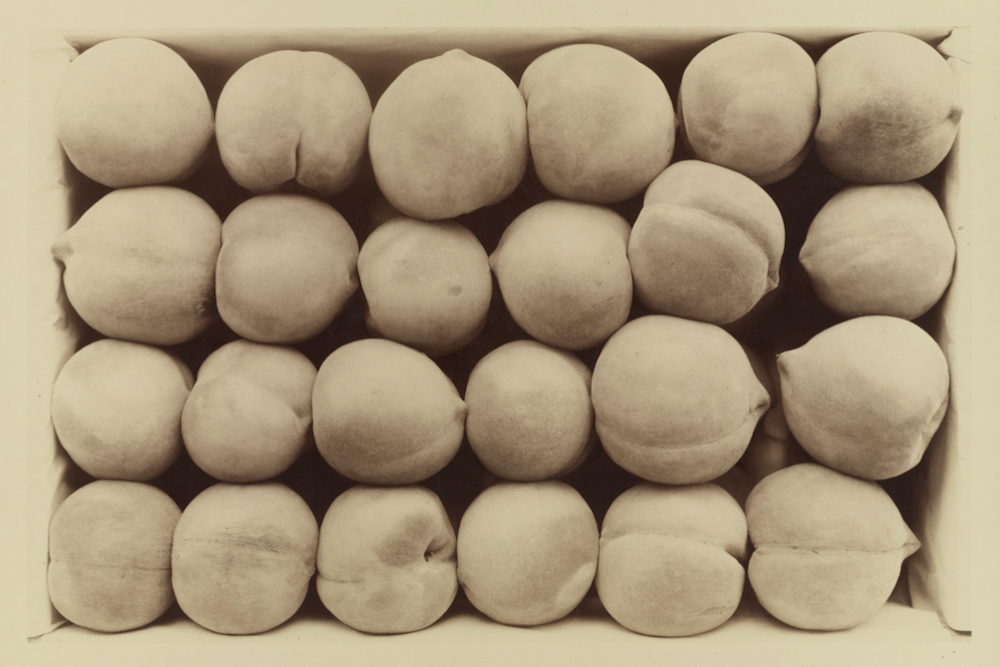

Late George Cling Peaches, a photograph by Carleton E. Watkins. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Not my usual route to the market—past

the railroad tracks, then past

Grace Episcopal Church,

its courtyard empty—no men

clasping hands as though agreeing,

finally, to the difficult terms

of some treaty—so I would not

have known it was a peach tree

unless the person who planted it

or someone on the street

told me. Which is not to say

its fruit didn’t look

peach-like—it did…

rather I didn’t read it as such, didn’t

know what I was

seeing, really—from where I stood

the fruit perfect and young

and heavy, at least heavy enough

to bow the branches, though hardly

ready yet to eat. Ripe,

one might say, which, true,

is more precise—precision

a thing of value. Not that

the fruit cares what you call it.

Or stands for anything

other than what time can make

of some small human intervention.

Is no piece of literature.

The peach was simply a peach,

and there for the taking,

which is often said of an object that has gone

unwatched for too long, susceptible

to trespass, which happens

first in the mind, and happened first

because of fruit,

or so says The Good Book

if you believe in such things. Knowledge,

which a poet once called “historical,” too

a trespassing of sorts, the proof of which

perhaps best shown in how one

might punish a slave who had been

taught to read the word beauty or toil

or rest, secretly, and by firelight.

There are things nearly impossible

to forget, having so trespassed,

having badly needed to see up close

this tree fixed in place, its fruit

dangling—there

within reach, though not

the same as being offered.

Tenderness, I have learned,

is only one test

of whether some fruit

has fully ripened. You

press the flesh right here. But for me,

that would mean crossing

half the yard the way a paper boat

might be pushed, by wind, across a pond.