Courtesy of Talib Jabbar.

At 938 feet above sea level, Mount Davidson is the highest natural point in San Francisco. And for nearly 30 years, since I was a child, it has been my point of return.

I was born and raised here, in this peninsula of unceded Ohlone land developed into a golden imperial city—the redwood empire—that now holds brightly colored homes and skyscrapers amidst its dramatic hillsides.

Mount Davidson is the first place I would visit anytime I moved back from elsewhere—Washington, Malmö, Lahore. And it’s where I go when a million things are happening: pandemics, wars, labor strikes, racism, planetary disasters, homophobia, heartbreaks. Mount Davidson is where I come to try to make sense of the world and orient myself.

The trailhead is located just south of the geographic heart of the city. It lies behind the bus stop—a small, worn down shelter with graffiti scrawled on the thick glass enclosing its backside. The stop services the 36 bus line, which is the one I rode home from my high school across town in the avenues, the third and final transfer before finally winding uphill into my residential neighborhood.

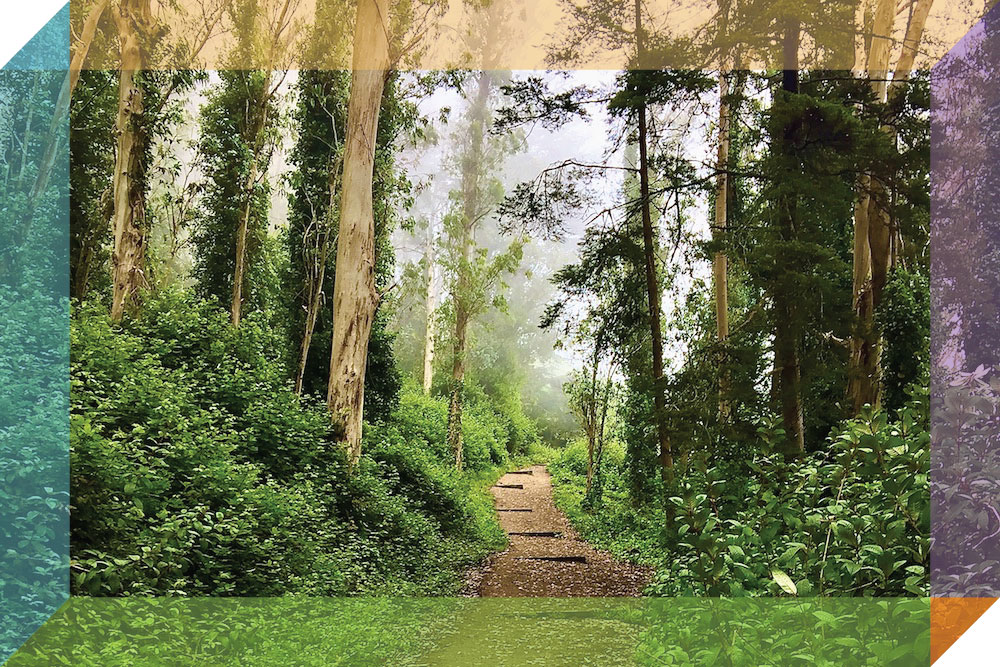

Courtesy of Talib Jabbar.

These days, I ignore the signs near the entrance, having read them hundreds of times: coyote warnings, a brief history of the park’s land transfer, and a list of rules for you and your dogs posted by the San Francisco Recreation and Parks. The signs act as markers of a threshold, a portion of the park being privately owned land for public use, infringing upon common notions of ownership—what’s mine is yours is ours.

The trail itself is a designated dirt path bounded mostly by blue gum eucalyptus trees, their unmistakable smell lingering like dried tea leaves. By the time I’ve gotten ten feet onto the trail, I leave the city—its bus routes, its paved schema.

The initial climb is in the midst of that wooded patch that wraps around the majority of the hill. It’s a steep incline but I’m used to it. I ignore the burn in my calves and instead focus on the foliage of tiny blue wildflowers, poppies, hog fennel, and those wild red berries my childhood friend told me were poisonous, so my sisters and I never dared eat them. I wonder if it was a childish deceit, but I still don’t dare eat them.

As I continue on, I hear the singsong of birds, the whisking of the wind through the tops of trees, a dog in the distance; all accompaniments to the fusing of urban and wooded. When I near the top of the first incline, I’m met with the first view of the city’s skyline, and it thrills me to see the built world from that hilltop set within a forest. In that way the space feels like a paradox, something liminal between reason and spirit.

The houses that line the roads leading upward appear stacked on top of one another, a palimpsest of architectural modes that defined entire epochs—as Dickens might say, it was the best of styles, the worst of styles.

I advance further and make it to the clearing. The large fallen tree is still there with its roots exposed on the northern side of the slope. Its thick branches are smoothed over now like giant antelope horns. Behind it is the most visible of landmarks, Sutro Tower. A still functioning radio tower—big, American-red-white-and-blue—it blinks like a north star for city-goers from the North, East, and South. Adolph Sutro, who is survived by several eponymous landmarks, recruited laborers and schoolchildren as arborists to plant eucalyptus and pine all along the western sides of this urban mountain.

Courtesy of Talib Jabbar.

From the clearing I can see all three bodies of water spilling into one another around the peninsula. The San Francisco Bay, dotted with cargo ships, extends southernly around the San Bruno mountains while the Golden Gate strait pokes out from behind the Twin Peaks that block the view of the famed suspension bridge. Westward, you can make out the edge of the sea, a roaring, watery border that is the geographic and temporal end of the contiguous United States. It looks calm from up here.

I can see the foam riding atop crested waves and imagine them washing soundlessly onto the shore of Ocean Beach, where I once had bonfires with my friends in middle school. It’s also the beach where I cut class for the first time in high school to ride the bus down Geary Street and jump into the numbingly cold Pacific. Wet clothes didn’t bother me back then; I felt alive in my skin.

I climb further up the rocky steps which are cut from radiolarite sediment, traces of microscopic sea life hardened into skeletal deposits that make way for hillside hikers. I pass the bench that sits facing the city with graffiti scrawled on its back, telling the world: I was here! I strain to see if I recognize the tag from a kid I once knew but figure it’s the trace of the next generation of recalcitrant youth. It was up here I indulged my own rebellious spirit imbibing in booze provided by the private school kids who rolled kegs up the hill.

In those days the fog always lingered, having rolled in during the late afternoons even on the sunniest of days. The fog would enchant the forest, a mist hanging over our indiscretions, like a scene from the neo-noir Dirty Harry, which filmed here in 1971. Nowadays, the fog seems to have burnt off more permanently, coming around only every so often.

Courtesy of Talib Jabbar.

At the second clearing, the very top, I pass the tribute to Mrs. Edmund N. “Madie” Brown, a bronze plaque installed on a rock. Her story goes something like this: She treasured the natural respite of Mount Davidson and, drawing upon her resources as president of a PTA, arranged for students and parents to flood the offices of the Board of Supervisors with wildflowers gathered from the hillside, which convinces them to preserve the area from building developers. She deserves the rock.

This rocky perch is a vantage point to feel above it all and at the precipice of something. It’s where I came the morning after the election nights of successive presidents, one a morning full of promise, the other despair. I remember that one day soon I’ll have to take the dirt path back down through the eucalyptus, tune in, distill information weighed against my ethics, deliberate, and vote again. I’ll do it based on my entire history, or at least whatever I can remember. I’ll fantasize about the days when you could swing politicians with wildflowers.

Several steps westward from Madie’s rock, it finally comes into view: the looming concrete cross, 103 feet tall. It always feels surreal, as if I’ve just happened upon it in the middle of the thicket. Like the city itself, the cross’s previous wooden iterations were burnt to the ground several times. As one of the signs reads, the City sold the land the cross stands on in accordance with the principle of separation of church and state. The Council of Armenian American Organizations of Northern California purchased it, hence the plaque that sits at the base of the cross commemorating the victims of the Armenian genocide and urging its readers to heed a lesson by remembering that magnitude of evil in the world. The cross still serves as a site for pilgrimage, especially on Easter Sunday. The story of the large concrete cross poking through the forest always feels worked out—settled through a series of compromises—at least for now.

Courtesy of Talib Jabbar.

Time up here is measured personally, communally, historically, and tectonically; all at once.

Taking in San Francisco from this vantage point, I try hard to remember the mythic city: one that celebrated diversity and dance and the arts and music and jazz and punk and sex and freedom and love and dignity and respect and values and trees and humility and courage and class and knowledge and power and beauty and performance and devotion and collectivity and always becoming and not foreclosure.

There is still surely something left of those past versions. Questions are plentiful and grandiose, answers impoverished. Up here I can at least think myself into some semblance of an answer, or at the very least, a response.

Send A Letter To the Editors