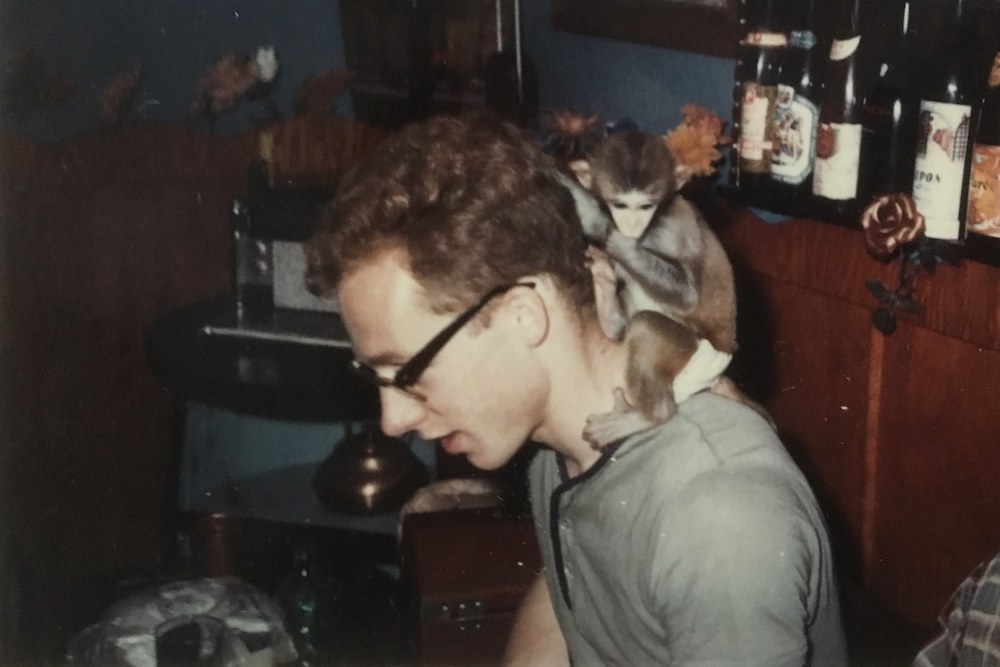

As a graduate student, Dr. Kurt Fischer “adopted” Frodi, an infant rhesus monkey, in order to study her. Courtesy of Seth Fischer.

A few hours after I learned my dad had died, my stepmom called me on speaker to ask if we wanted a post-mortem COVID-19 test. I was pacing my living room in Los Angeles, wishing more than anything that I could get on a plane, but knowing that this would do nothing but risk more death. My stepmom was in a room full of nurses and administrators at my dad’s memory care facility in Boston, and they were pushing her hard not to ask for a test, even though he had died from what they called “acute respiratory distress.”

It was late March, early in the pandemic, and tests were scarce across the United States. But there had been an outbreak on his floor. One resident had died already. The medical and scientific community still knew little about the disease.

I liked his caretakers. They’d called him Dr. Kurt and showered him with song and touch, even though his Alzheimer’s disease had advanced to a phase where he couldn’t say anything but “yes,” “no,” and “stop it,” much less know what kind of doctorate he held.

But our relationship with the facility had gone to hell when the pandemic hit. They’d failed to tell me and my family that we’d been exposed when we visited. They’d waited several days after the first staff member was diagnosed to email families. They’d ignored my attempts to find tests and protective personal equipment for my father and other residents.

So, against their wishes, I demanded a posthumous test.

Over the next few days, my family and I were told a lot of things. Massachusetts said it was our legal duty to get him a test, both to track the outbreak and to protect the other people at his facility. The Boston Public Health Commission said that under no circumstance could he get a test because there were not enough, and living people needed the tests more than him. We even received notification that he was turned down for hospice because, when evaluated the day before his death, he’d been “too healthy.”

But simmering underneath almost every conversation was a sentiment I heard out loud from one man at the Boston Public Health Commission. “With all due respect,” he said, “he’s passed either way.”

It still mattered, I thought but didn’t say. My dad, by many accounts a “scholarly giant” in the fields of developmental psychology and education, had lived his life devoted to scientific ways of thinking, so much so that he thought quoting research studies at me would persuade me to behave as a teen. To him, a lack of structured curiosity would not just lead to moral and scientific ruin; it was also a sign of disrespect. So during all of the bureaucratic conversations I had after his death, I could hear his voice, being the scientist that he was, insisting on learning the why and the how.

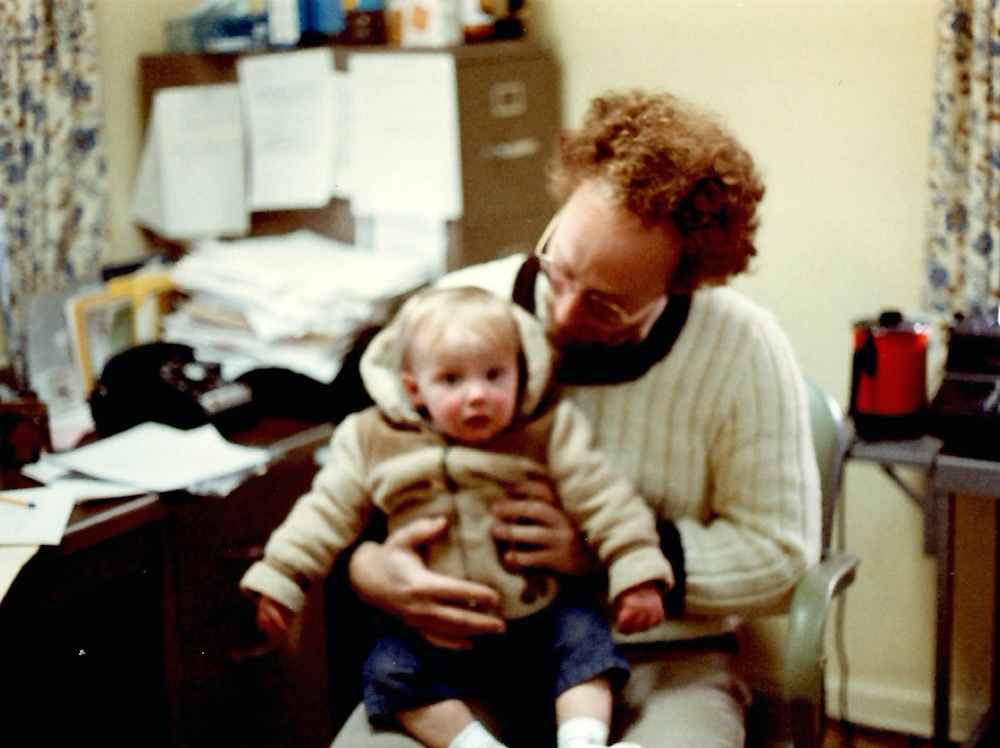

Courtesy of Seth Fischer.

Though I knew he was a successful academic, I knew little about the specifics of his research until I heard his colleagues speak at his retirement colloquium, after his Alzheimer’s disease had made it too late for him to discuss it. Thankfully, about a year before he died, I had the chance to excavate his basement office in my childhood home just outside Cambridge. It was a place he had forbidden me from entering as a kid, but now, it was mine.

I breathed in mold and papers that had spent decades wallowing in his colleagues’ cigarette smoke. Dozens of boxes filled with typewritten and dot-matrix paper were balanced awkwardly around the room.

Maybe here I could get some answers about who he was. We weren’t estranged, but he was the kind of dad who, when we had a disagreement, would tell me, “That’s typical for someone your age”—even when I was 7. This approach to fatherhood, coupled with the disaster that is modern masculinity and a fight when I was 15 over my parents’ custody agreement, had made us near-strangers who also loved each other more than anything. I can’t think of a single time as an adult, pre-Alzheimer’s, when we both acted authentically in a room together.

I was fascinated by his professional legacy. He consulted with everyone from Pope John Paul II to Sesame Street to the Chinese government. His colleagues at the Harvard Ed School, where he taught for 27 years, told me his research had improved the lives of thousands, if not millions, of students and educators. He did this in part by creating “dynamic skill theory,” which argued that human development was a complex and dynamic interaction between culture, context, and child.

This was and is a revolutionary idea because it implies that we are all complex individuals with different trajectories. Many other theoretical frameworks are built around the “normal” person, focus on “teaching to the mean” or average student, and can sometimes lead to punishment, neglect, or other less-than-ideal results for people who develop differently or in ways we don’t understand. He urged, instead, innovation and a respect for complexity. One of his mantras was, “Explain variation. Don’t explain it away.”

He also co-created the journal Mind, Brain, and Education and its entire field of study, bringing together educators, psychologists, neuroscientists, and others—a tough sell in the rather siloed corridors of academia at the time. After speaking with his students, I learned that one of his core beliefs was that children, educators, and scientists of all kinds are important to understanding development, no matter how different their perspectives. And he fiercely believed that we could all change the world if we respected each other and worked together.

It’s astonishing to learn how much he accomplished and grew, especially after reading the Frodi journals I found in his basement.

When my dad was in graduate school in developmental psychology, his professor encouraged each of his students to get a rhesus monkey, raise it, and take notes to better understand its development. My dad was the only one in his class to do so. When he found one, he named it Frodo, then renamed it Frodi when he realized she was a girl, and moved her into his tiny Cambridge apartment in May 1966.

In the year or so he lived with Frodi, he filled two notebooks with handwritten notes. Many revolve around my dad’s quest to make her stop peeing on him in the shower. At one point, he took her through Grand Central Station during rush hour, and, not surprisingly, she made more noise than he wished.

But what is most intriguing about these notes is the tone.

“Two things have been salient, especially about her recent behavior to strangers. She has reacted especially warmly to a few stranger girls or women, but has begun to show threat gestures to some other strangers, especially when they poke at her.”

The language and content are absurd. Does anyone like to be poked? Is it not obvious to him that Frodi might be taking cues from his body language, rather than reacting to the gender of human strangers? How could he pretend to write in the language of an impartial scientific observer when he is so clearly a part of what is happening? How could he be so bad at listening?

I chuckled and put them aside. Fine, I thought. He was only 23.

But then, in the next box over, I found something more disturbing: a black, 11-inch-by-13-inch three-ring binder from when he was in his late 30s. I looked inside. My name was everywhere. These notes were just like the ones he’d taken on Frodi, but they were all about me. What’s more, he’d convinced my mom, another psychologist who had once been a student of his, to take notes, too.

Courtesy of Seth Fischer.

The first page I read held notes on an experiment: He picked up a pacifier and kept it always just out of my reach, to see if I moved my hand to grab it. Then he repeated it with my stuffed Woodstock. He changed the position eight times. By his account, I “continued to try to grasp it,” he wrote, “but the grasp continued to be awkward.”

The notes have the same frigid, judgmental tone as the journals about Frodi. I pass and fail. I’m awkward or successful. In the most disturbing of these experiments, my parents repeatedly sat me in front of a mirror and tried to get me to pass something called the “rouge test,” which measures self-awareness by putting rouge on a kid’s nose and testing whether they touch their own nose or the mirror. At first, they just wanted me to sit there, to get me used to it, starting at about six months. Then, a couple months in, they started the tests.

I resisted this experiment more than any of the others, but they kept making me stare at myself, no matter how much I cried. The number of attempts each time, over a period of seven months, is put in terms of n: “N=8.” “N=12.” “N=3.” It was never clear what counted as a full attempt. I can only guess that each “attempt” meant they persisted until I became so frustrated they had to stop.

Finding these made me wonder if he ever thought of me as a person, or if he thought of me only as a test subject. They made me wonder if he knew how to love.

But then, under the folder, I found hundreds of pages of my childhood drawings. Then I found another box full of my art. Then another.

The art was uninspired, of course, even for a kid my age. Red and orange and green and blue blobs. When I got slightly older, a blobby stick figure, or a blobby house, or a blobby sun. I was not a gifted artist. Still, each one of them was marked with my name and the date, as if they were intended for a future research project.

Or was it because he cared about me?

Maybe, I thought, it was both.

On my father’s death certificate, the doctors listed four primary causes of death: probable aspiration, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), Alzheimer’s disease, and adult failure to thrive.

“Adult failure to thrive” is a common cause of death for Alzheimer’s patients, because there is no good scientific way to say that everything kind of stopped working.

Courtesy of Seth Fischer.

Reading these four words, I recognized the same language he’d used in his notes on Frodi and me: cold, judgmental—and morbidly funny. This is the nature of so much of the language of medicine and science. It is used, I assume, in service to objectivity, but it makes scientists and doctors seem more obtuse than objective. Science’s fundamental impulse, we hope, is to better humanity, but it often forgets that the way it answers our most important questions matters.

My dad took notes on me because he was curious, and because he believed that the best way to love me was to study me. This also meant, to our detriment as father and son, that his love sometimes looked like whatever brand of science he was using at the time. And if my recent experiences with the medical, scientific, and government communities during his death are any indication, the oblivious way of approaching science that he used all those years ago is alive and thriving today.

We never got the test. COVID-19 was hitting Boston hard, the mortuary needed the space, so we had to bury him before we could get his doctor to return our calls.

Last summer, I spent a month reading through everything my father ever wrote. I could see an evolution in his work over the last 40 years, an evolution I missed until it was too late to ask him about it. I could see this shift most clearly in an address he gave to the Swedish Parliament in 2011.

In the talk, he completely loses control of his hands—which he does when he’s excited—while talking about dyslexia. People with dyslexia look at the world differently, he says, not better or worse than anyone else. He points out that astronomers with dyslexia are far better at finding black holes, and that thinking about dyslexia without judgement has transformed what is possible for children with dyslexia.

He had long ago evolved beyond the young man who had framed Frodi’s actions, and mine, in terms of passing and failing. If we view subjects as humans, he had learned over the decades, if we take off the veneer of coldness and judgement at the heart of much scientific thought, we will soon find ourselves getting better answers.

And it was his dual focus, late in life, on both humanity and finding answers that makes me think he would have been livid at the way his death was handled. It wasn’t just that knowing whether he had COVID-19 would have been kind to his family and to his caretakers, though that would have been foremost on his mind. It was also that his case might have helped scientists learn something.

If he were alive and well today, if he were watching millions sick or dead of a new illness while our political and medical institutions crumble around us, I like to think the advice he’d give us is this: It is time to fight fiercely for a warm and broadminded approach to science and medicine, for a humble understanding of humans as complex, varied, and dynamic creatures.

This is true for moral reasons, but it is also true for practical reasons. The best way to be kind is to be curious, and the best way to be curious is to be kind.

Send A Letter To the Editors