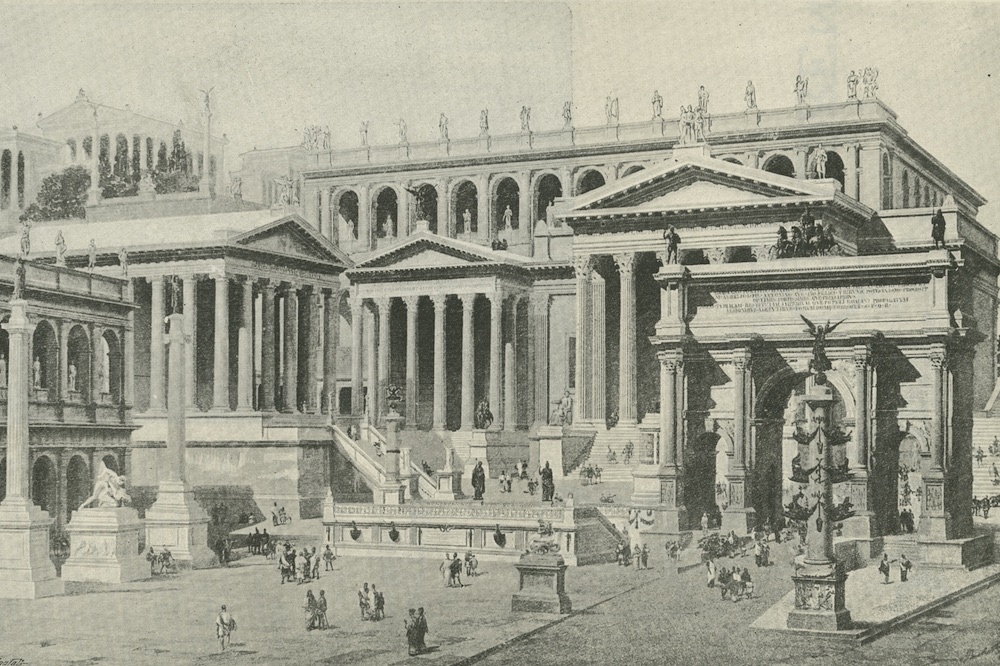

A view of Rome’s Capitol and Forum as reproduced from a painting by the Italian painter Buchetti. Courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Collections.

A politician-incited, post-election riot at a Capitol, seeking to block the result of a peculiar voting system, is not news. Ancient Romans witnessed something very similar.

On December 9, 100 B.C., Romans assembled to vote for the two consuls who would serve as the Republic’s top magistrates for the coming year. The election promised to be momentous. Gaius Marius, the dominant political figure in the Roman Republic for the previous decade, was finishing his fifth consecutive consulship. Once an extraordinarily popular figure, Marius had only won his most recent consular term through widespread vote-buying and intimidation.

Marius’s behavior in office had been even worse than his campaign conduct. In alliance with two radical populists, the tribune Saturninus and the praetor Glaucia, Marius spent much of the year before the election mobilizing angry crowds that violently backed laws that benefitted their partisans and punished their rivals—in one case even beating their opponents with clubs after polling had begun. So Rome seemed ready to move on.

Marius was not on the ballot that day, but Glaucia was. Glaucia understood that an electoral victory might again depend upon violence and intimidation, and so his supporters came to the polling place, hoping he would win but ready to fight if that would prevent his loss.

Roman magistrates did not win election by simply carrying a majority of the popular vote. Roman elections for consul were instead decided when candidates won a majority of Rome’s 193 voting centuries. The voting centuries were neither equally distributed across property classes nor were they the same size. The wealthiest Romans had the most centuries in the assembly, but their centuries had far fewer members than the ones to which poorer Romans belonged. Romans nevertheless accepted that a successful consular candidate needed to win the support of 97 centuries, regardless of their raw vote total. This was, in a way, a Roman analog to our own Electoral College.

Also, as in 21st-century America, there was a ceremonial aspect to how Romans announced voting results. Each century announced its vote separately, one at a time, until the votes of 97 agreed. And, as the votes were cast on that December day, it became clear that Glaucia would lose the consulship to a man named Memmius. Rather than accept this outcome, he and his supporters rioted. They disrupted the vote counting, attacked Memmius, and beat him to death. The assembled voters fled in terror before the election could conclude.

The Roman historian Appian wrote that “neither laws nor any sense of shame” remained among Romans after the bloodshed began. Supporters of Glaucia battled in the streets with their rivals, before retreating, along with Glaucia and Saturninus themselves, to the Capitoline Hill, the ceremonial center of Rome’s Republic and the place from which our Capitol building derives its name. The insurrectionists then seized the Capitol and barricaded themselves on it.

The Roman Senate invoked a constitutional measure called the senatus consultum ultimum, a rare emergency action that empowered magistrates of the republic to use whatever means they had at their disposal to save Rome’s representative democracy. This time, the person the Senate chose to put down Glaucia’s seizure of the Capitol was none other than Glaucia’s associate, Marius.

Marius faced a wrenching decision. Much of what he had accomplished during the past year came from his deft use of populist rhetoric and political intimidation to excite a base he shared with Glaucia. Marius had looked the other way when Glaucia and Saturninus used mob violence to push Marius’s policy goals and punish Marius’s political adversaries. The senatus consultum ultimum meant that Marius could no longer pretend not to see Glaucia’s abuses. He had to act—or face charges that he was complicit in Glaucia’s insurrection.

Appian tells us that Marius “was vexed” about whether to defend his old ally or defend his state, but he ultimately chose to defend the Republic. He “armed some of his men reluctantly,” approached the Capitol with his troops, and surrounded the hill until the water supply was cut, forcing Glaucia and his men to evacuate.

But that didn’t end the crisis—it only relocated it. Marius, hoping for peaceful trials of his allies, granted Glaucia and his men safe passage down from the hill to the curia, the building where the Roman senate often met. Once Glaucia and his supporters reached the curia, though, an angry mob appeared and set upon the insurrectionists—killing them with a barrage of tiles broken off of the chamber’s roof.

No Roman woke up that December day imagining that the election to choose one of Rome’s top magistrates would end with one candidate killed during the voting and another dying with his supporters in the Senate House. Romans worried constantly about their lawful Republic descending into anarchic violence, but none imagined that this descent would happen so quickly or with such terrible results.

Americans today face a similar moment of shock, and reckoning. On a day when our Congress was supposed to perform the ceremonial task of accepting the electoral votes for our next president, this democratic exercise was halted by violence. Like Glaucia’s mob in 100 B.C., the Washington insurrectionists were incited by the candidate who was about to officially lose the election. With his encouragement, they marched to the Capitol carrying weapons and bombs, stormed through its gates, and interrupted the vote tallying. They were met with gunfire. At least one was killed.

Donald Trump could not even muster the integrity that Marius showed. Instead, Trump expressed love for his supporters, and offered only the most lukewarm criticism of their actions.

It is hard to overstate the damage that a day like this can cause to a republic. The violent disruption of the consular vote in 100 B.C. initiated two decades of political dysfunction that led to the first civil war in Rome’s recorded history. That fighting ultimately deprived hundreds of thousands of Romans of their lives or property.

That’s why Americans must not dismiss, or move quickly past, the events of January 6, 2021. Our leaders and regular citizens must respond far more forcefully to an assault that targeted not just the seat of government, but the democratic rights and protections we enjoy. We need to condemn more clearly the insurrectionists’ actions, to identify and punish all the perpetrators, and to remove the instigators from our public life. If we cannot do that, sedition, insurrection, and political violence threaten to become the most potent political tools in the America of the 2020s—just as they did in the Rome of the 90s B.C.

Send A Letter To the Editors