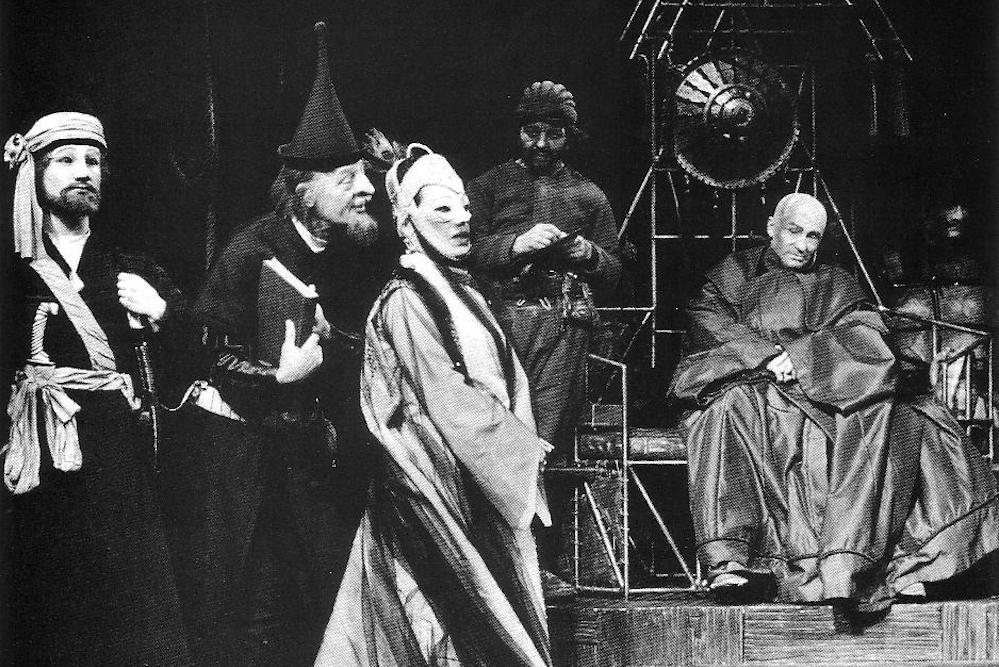

A performance of Bertholt Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle staged in 1954 by the Berliner Ensemble. Nachlass Siewert im Forum für Nachlässe von Künstlerinnen und Künstlern e.V./Wikimedia Commons.

“All the gang of those who rule us

Hope our quarrels never stop

Helping them to split and fool us

So they can remain on top.”

— Bertholt Brecht, Solidarity Song

How strange to watch Trump’s failed insurrection on Congress unfold from one’s living room TV during COVID lockdown—sidelined by stay-at-home orders, reduced to binging the way one might devour The Queen’s Gambit or Ozark into the wee hours with snacks and pets sharing the couch. Watching an attempted coup was a strangely stupefying and passive experience.

It all looked a bit like a mash-up of movie motifs—angry white mobs with pitchforks from Frankenstein, many resembling extras from Hillbilly Elegy, self-righteously storming the seat of power, each addled MAGA-wearing inglourious basterd starring in the action movie of their life.

Even as we wondered how far the horror show would go, there were numerous moments along the way that seemed staged, performed almost pro forma, for the benefit of the larger narrative. Perhaps this was Trump’s obligatory scene, anticipated by the national audience and provided by the willing protagonist after years of veiled and not-so-veiled promises and gestures worth a thousand words.

In a sickening way, the storming of the Capitol was a real-time made-for-TV event, an entertainment designed to mainline directly to the emotions and to narcotize the critical eye, leading straight to racism, xenophobia, demagoguery, and fascism.

At least that’s what Bertholt Brecht would have thought. The great German playwright, who had a front-row seat to the early acts of the Hitler show, found his answer for such theatrical manipulations in 1936. Verfremdungseffekt, shortened to the V-effekt or awkwardly translated into English as “the alienation effect,” was meant to cause a jolt that forced an audience awake and into an analytical mind. Brecht was intent that the viewer be disabused that the play they were watching was somehow predestined, inviolable, or written in stone: He wanted them to understand that what they were watching was real.

Brecht knew that reality is corruptible, particularly when presented in emotional terms by skilled storytellers. Drama can give dimension to grievance, blood and thunder, and make it all seem true as gospel. The playwright could use V-effekt to carve out alienation and distance from the emotional demands and expectations of lead characters. Rather than settling back and being entertained by the story, Brecht asked his audience to sit up and pay attention to the tells—the unconscious clues that, when put together, help reveal the fundamental manipulation taking place.

Traditionally, the playwright employs the V-effekt. But with stakes as high as they are now, it’s up to us to stop the sturm und drang. Applying the V-effekt to the events around the failed putsch demands that we jolt ourselves awake, whether we are watching it unfold on FOX, MSNBC, or 4Chan. We are participants, too, even if we are made to feel otherwise.

Perhaps it’s Azdak in Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle who most embodies the jolt that awakens the audience, destroying their illusion of being unseen spectators in the events taking place by addressing them directly. Facing rampant injustice, including the successful coup by a “Fat Prince,” Brecht stops the action and introduces us to Azdak, the witty and corrupt judge who must determine who is guilty and who is innocent. Announcing his proclivities upfront and revealing his weaknesses for wine and women, he makes no attempt to hide his unsoundness as a judge. Yet precisely because of his very human vanities, he proves to be a keen arbitor of wrong and right.

“You want Justice, but do you want to pay for it?” Azdak asks. “It is good for Justice to do it in the open. The wind blows her skirt up and you can see what’s underneath.”

Torsten Schemmel plays the role of judge Azdak in Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle (Vorpommersche Landesbühne 2009). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

This is our time to demand to see what’s underneath. According to multiple news sources, Trump-friendly internet users described the assault on Congress as “like a movie” and “the best show they’d ever seen.” The trouble, of course, is that it was not a movie. It was real. People died.

Despite identifying emotionally with their leading man, the Capitol rioters were blind to the fact that Trump actually had little or nothing to do with them or their interests. In his rabble-rousing speech at the Save America rally just before the assault, Trump promised to walk alongside his fans; of course, he was nowhere near when the deal went down.

As reality-star-in-chief, he groomed us to expect the narrative he unfolded to be performed yet again by others on his behalf. Trump’s story was designed to aggrandize him while giving his devotees their very own part in a real-life action movie.

Telling a lie over and over can make it seem true. It can also remove agency from the viewer, ceding the individual’s judgement over to the expectations of the story being told. Brecht refused to let his audience lose themselves in the funhouse mirror of such representations. “Art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it,” he wrote.

Watching the events of the Capitol insurrection and its aftermath, I found myself searching within for that same symbolic hammer—not as a weapon or a shield but as a tool to jolt myself awake, to shake off the dopamine effects of four-plus years of the Trump saga and to pound out an alternative to their zero-sum fallacy.

It helps to be a playwright. Our vocation is not tethered to capital in the same way as screenwriters; we can, and usually do, lose money on our creations. It dawns on most of us over time that it’s better that way, that the artistic freedom to tell an inconvenient truth can coexist somewhat—but not entirely—with capitalism. At a certain point, the narrative needs a jolt, even if it means biting the hand of our benefactors and awakening the ire of our audience.

It’s long been said that theater is an invalid at Death’s door, yet theater hasn’t expired in 2,500 years. I like to think it’s partly because the best playwrights take a hammer to the zero sum of their reality and reshape it.

The reshaping involves intellectual empathy, the ability to consider the experiences of others—not just who they are but where they come from and what they’re reacting to. Intellectual empathy can be grown, but it takes work. One must support diverse and unpredictable responses from individuals about the story they are seeing. One must deny groupthink and the urge to join the throng making pat conclusions because it feels good or it is expected of them. Intellectual empathy extends beyond the binary conventions of tribalism. It analyzes characters on and off the stage and judges them not just on what they say but what they do.

The continued indignation on both sides of the political aisle in America today is simply another narrative convention, pre-determined, even programmed deep within us. If we’re not careful, our emotional investment gets us stuck in a Marvel Comics world of superheroes and supervillains who fight for or against us. One bad real-life movie begets another.

What we need to be doing, instead, is fighting for ourselves. If we want to change the story of our country, we are the ones who need the alienation effect, and we need it now. The movie conventions of endless cause-and-effect and kneejerk action-reaction need to stop. The narrative needs a reboot.

Describing his V-effekt, Brecht writes:

Reality changes; in order to represent it, modes of representation must also change. Nothing comes from nothing; the new comes from the old, but that is why it is new. Every art contributes to the greatest art of all, the art of living.

Perhaps the failed insurrection was the jolt needed to reawaken our intellectual empathy. It remains to be seen. The story is ours to tell.

Send A Letter To the Editors