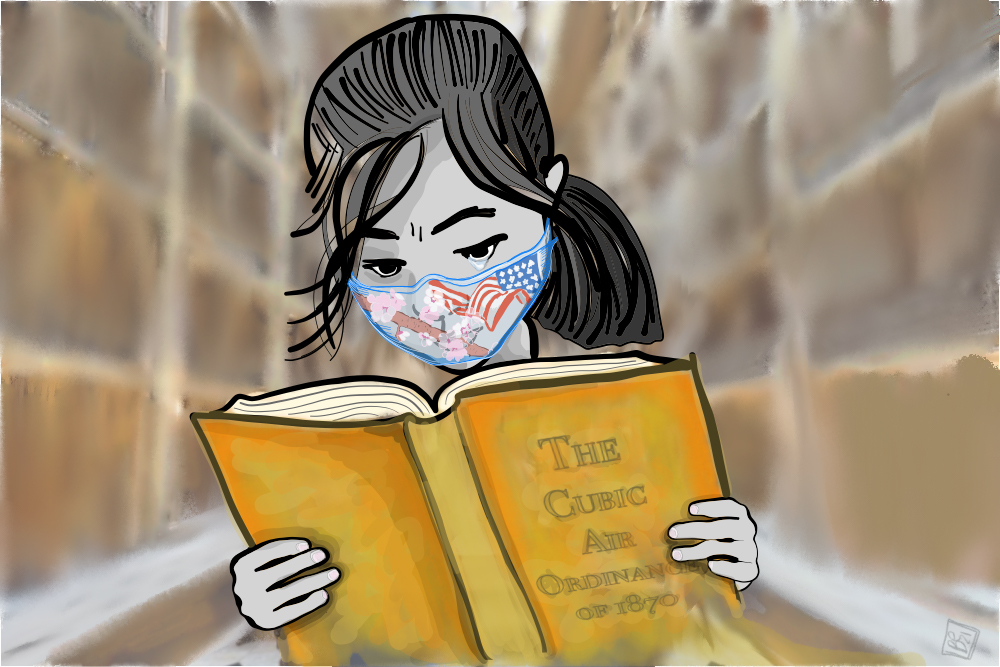

Illustration by Be Boggs.

Since the early months of COVID-19, people assumed to be Chinese have been stared at, yelled at, coughed on, spit on, sprayed with Febreze, beaten, splashed with acid, pushed, stabbed, and murdered—for wearing masks, for not wearing masks, for coughing, for sneezing, and sometimes for simply occupying public space. I have thought twice about spending time in public on days when allergies to cats, pollen, or wildfire smoke might make me susceptible to the hazards of “coughing while Asian.”

The anti-Asian violence was spurred on by widespread rhetoric projecting blame for the COVID-19 pandemic onto China and people of Asian descent. But the stigmatization of Chinese immigrants as a threat to public health and safety has a long history in the United States. It emerges from an entrenched mode of racism that targets not only Chinese bodies, but Chinese air.

What do I mean by “Chinese air”?

Answering that requires returning to the epidemic of violence that swept the West after Chinese immigrants began settling in the U.S. in the 19th century. White Americans refused to live in proximity with Chinese settlements—literally, they refused to breathe the same air. The consequences were deadly. A mob massacred 19 Chinese men in Los Angeles in 1871, and anti-Chinese race riots erupted in cities such as San Francisco, Vancouver, and Seattle. Living on the periphery was no protection. As urban travelers in the West rode railroads built by Chinese migrants to take in the pure air of nature resorts, more than 100 violent purges forced Chinese immigrants out of rural settlements and into overcrowded, poorly ventilated accommodations in urban Chinatowns.

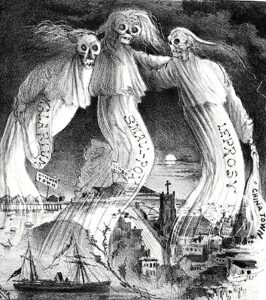

At the time, many scientists didn’t understand that microbes spread disease. Instead, they believed that illness was transmitted through poisonous air or miasma and endorsed changes to urban planning and sanitation in their efforts to sustain public health. Anti-Chinese agitators quickly adapted miasma theory as a tool in their campaign. Even after germ theory gained acceptance in the 1880s, they stigmatized Chinese air and smells, associating overcrowded spaces, laboring bodies, opium smoke, culinary odors, and incense in several urban Chinatowns with disease.

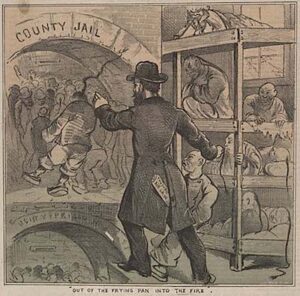

An image published in The Wasp magazine depicting Cubic Air Law arrests—Chinese men being moved out of a crowded apartment into even more crowded jails. Courtesy of public domain.

As the historian Nayan Shah has documented, 19th-century San Francisco public health officials regularly blamed Chinatown for the city’s recurring outbreaks of diseases including smallpox, tuberculosis, cholera, and bubonic plague. In response to the 1868 smallpox epidemic and working-class agitation against the Chinese, the city’s Board of Supervisors passed the Cubic Air Ordinance in 1870, requiring that dwellings contain at least 500 “cubic feet of air” per adult resident. This law was enforced exclusively against Chinese people, and critics noted that the city detained Chinese immigrants in jails that were much more overcrowded than their homes. The Cubic Air Ordinance thus targeted Chinese people not only as foreign bodies, but as deviant assemblages of bodies and air.

Sanitation became a common pretext for disciplining and displacing Chinese residents. In 1903, the physician Woods Hutchinson praised San Francisco’s health officials for adopting aggressive cleaning methods: “The seven and thirty separate smells of Chinatown have all been drowned in one grand olfactory delirium of chloride of lime and carbolic acid. Never was Chinatown so free from vermin.” Nevertheless, Hutchinson went on to declare that Chinatown “can never be cleaned except by fire.” He may have had in mind a fire that burned down 4,000 homes in Honolulu’s Chinatown, permanently displacing many residents—a conflagration that started when Honolulu’s Board of Health burned down buildings to control an outbreak of bubonic plague.

Hutchinson’s fantasy for San Francisco nearly came true in 1906. In the wake of the city’s devastating earthquake and fire, officials proposed relocating its Chinese community from the burned-out but centrally located Chinatown to far-flung Hunter’s Point. This plan, which was eventually stopped after intervention from China’s consul-general, presumed that the Chinese community would not be out of place amid the latter neighborhood’s slaughterhouses and industrial fumes.

On a smaller scale, American nuisance charges have also posited Chinese air as an offense to public well-being. In the 1880s, complaints about the smell of drying squid shut down a thriving Chinese community of squid fishermen in Monterey, California. More recently, similar protests have been lodged against Asian restaurants and food manufacturers, including the Sriracha sauce factory in Irwindale, California. In a 1999 case in Pennsylvania, grease smells from Wok’s Chinese Restaurant were deemed “noxious” even though, the defendant noted, they were comparable to the smell of burning wood from a nearby pizza restaurant.

An 1882 cartoon from The Wasp of disease figures hovering over San Francisco. The LEPROSY figure (right) holds a strand of smoke that says “CHINA TOWN”. Courtesy of public domain.

The notion of Chinese miasmas has had support from respected academics. In the 1890 essay “Mongolianism in America,” the historian and ethnologist Hubert Howe Bancroft (for whom UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library is named) wrote that he found it difficult to breathe when he walked through the crowded alleys of San Francisco’s Chinatown. “Faces swarm at every door, inhaling poison, exhaling worse,” he claimed. Bancroft never considered that he might be experiencing anxiety, triggered by his own discomfort with something unfamiliar. Instead, he speculated “whether a Chinaman’s lungs are not formed on a different principle from ours … He certainly seems to thrive in stench where others would suffocate.” Attributing Chinatown’s poor air quality to cultural and biological differences, so-called experts like Bancroft drew attention away from the forces of mob violence, poverty, social marginalization, and housing inequity that had pushed Chinese immigrants into substandard living conditions.

Because culture plays a powerful role in shaping olfactory responses, I have been studying how American narratives spread—and sometimes challenge—these ideas about Chinese air. Stories about Chinese stench date back to the first decades of Chinese immigration. In the 1860s, Mark Twain wrote about a San Francisco detective who could smell a chicken feather from a crime scene and “tell which block in Sacramento street the Chinaman lives in who committed it.”

The Yellow Peril has a smell in Frank Norris’s novel Moran of the Lady Letty, in which a white woman is held captive by a crew of reeking Chinese pirates. In Sax Rohmer’s The Insidious Fu Manchu, published in 1913, the first Asiatic supervillain attacks detectives with a mysterious poison gas, which leaves “no clew-remaining—except the smell.” By the time Raymond Chandler wrote that a character “had a sort of dry musty smell, like a fairly clean Chinaman,” “Chinese” had become a metaphor for stench.

Edith Maude Eaton, a mixed-race Canadian writer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who has been called the mother of Asian American literature, fought this pattern of olfactory stereotyping in her stories about domestic life in several urban Chinatowns. Writing under the pen-name Sui Sin Far (“Chinese water flower”) and titling her book Mrs. Spring Fragrance, she associated Chinese immigrants with pleasant smells.

When they could afford to, Eaton suggested, Chinese immigrants preferred a cool and fragrant atmosphere: “After the heat and dust and unsavoriness of the highways and byways of Chinatown, the young reporter who had been sent to find a story, had stepped across the threshold of a cool, deep room, fragrant with the odor of dried lilies and sandalwood, and found Pan.” Where the natural aromas of lilies and sandalwood indicate the careful housekeeping of the Chinese family, the smell of the streets was the result of the city’s failure—or refusal—to fulfill its responsibility of cleaning Chinatown’s streets.

The contemporary artist Anicka Yi took a more direct approach to olfactory racism in her 2017 Guggenheim Museum exhibition, Life is Cheap. The first installation consisted of three gas canisters emitting a blend of odors sourced from both a colony of ants and from Manhattan’s Chinatown and Koreatown. The main gallery featured two dioramas Yi created by using visually captivating bacterial cultures sourced from the same neighborhoods, and the same colony of ants inhabiting an enlarged circuitboard. The piece is a meditation on Asian stereotypes, and Western dependence on inexpensive Asian imports.

Not unlike Fu Manchu’s gas attack, the scents Yi works with—which she describes as vegetal, floral, citrusy, and meaty—insidiously penetrate the bodies of visitors. But the museum setting recasts the smells of Asian neighborhoods as an unusual olfactory experience, something to be sought after rather than avoided. Yi hints that inhaling the scents of Chinatown, Koreatown, and ants might predispose her audience to perceive their connections with the beautiful forms presented in her living dioramas.

Life is Cheap asks how smells usually thought of as foreign are already part of us, whether as bacteria inhabiting our bodies or as fumes emitted in the course of producing our computers and phones. After all, China’s industry and urban development are intimately connected with the U.S. addiction to cheap technology.

And, like the perceived unsavoriness of Chinatown streets, the conditions that promote COVID-19 are part of something much bigger than a wet market in Wuhan. Chinese air is not made in China, it is an exhalation of the global economy.

Send A Letter To the Editors