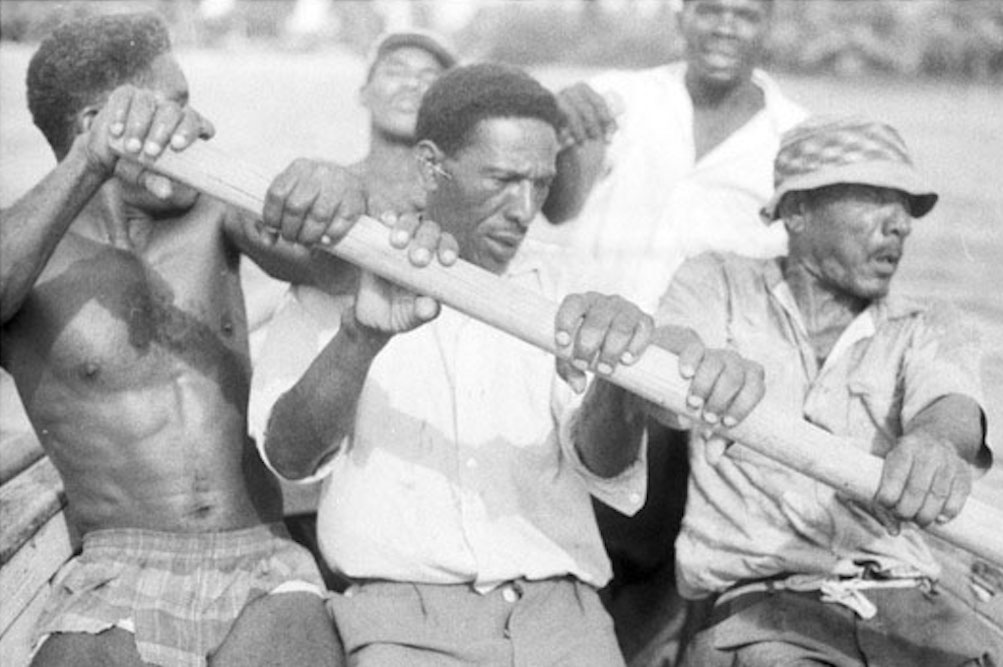

A group of oarsmen in Newcastle, Nevis, sang shanties for Alan Lomax in 1962. Photo by Alan Lomax. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The last time I visited my paternal grandfather, Elton Smith, Jr., at his Virginia home, it was 2018, and he was well into his 90s. As I interviewed him for a family memoir project, he sat regally on the couch, framed by a mantle of plaques, diplomas, yearbooks, newspaper clippings, family photos, and various items associated with Freemasonry. Amid all these impressive objects, what caught my attention was the understated insignia on his black polo shirt: a white anchor circled by the words “Northern Neck Chantey Singers.”

From the mid 2000s until 2020, Granddaddy Smith toured the East Coast, singing maritime work songs from the Northern Neck, a peninsula between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers. Some of his buddies had invited him to manage this group, founded by William Hudnall in 1991. Granddaddy, the church treasurer of Mt. Vernon Baptist Church in White Stone and a member of its men’s chorus, fit the groups’ needs nicely. He, the son of a fisherman, and the other five men, all retired African American menhaden fishermen, would visit schools and festivals, sharing a relic of the past that survived long after most of the fishermen in the region were replaced by automated systems. Beaming about the music, Grandaddy said, “When I got into it, I was carried away.”

Chanteys, sung in unison, allowed fishermen to coordinate their efforts as well as keep their minds off the tedious and backbreaking work. Engaging in this call-and-response work-song tradition, they would convey the wide range of their lived experiences: difficulties of their hard labor, critiques of their bosses, gratitude to the fish, supplications to God, and odes to the women they loved and missed when out at sea for weeks on end. Interestingly, there are various spellings of “chantey/chanteys” including “chanty/chanties” and “shanty/shanties” because the word was spoken long before it was ever written. (While the origin of the word is up for debate, “chantey” could come from the French chanter—“to sing”—or from English “to chant.”) Though the term has now come to describe any song sung upon the ocean, experts have noted that when referring to the seafaring work-song tradition, as those performed by my grandfather’s group, “chantey” is apt.

Granddaddy Smith’s favorite chantey is “Won’t You Help Me to Raise ’Em.” When the group performs this song, they show the audience how the fisherman would’ve pulled up the heavy net in unison. The leader calls out “Won’t you help me to raise ’em, boys,” and then the rest of the crew responds with the sweet resonances of their multiple voices “Hey, hey, honey” before tugging with all their might. Hearing this haunting chorus, it’s easy to imagine the music and lyrics imbuing the fishermen with enough strength to haul in their catch.

Before I started to research the Chantey Singers, I had never heard Granddaddy sing. As I watched a Library of Congress recording of him, he delivered the solo for what would become my favorite chantey, “Remember Me.” In his smooth baritone, he sang “Remember me / remember me / oh Lordy / remember me.”

As one of the only high-paying jobs available for Black men in the region, many fishermen toiled on the sea. Some met their deaths there. For instance, in 1938, when Granddaddy was 12, his father perished at sea in a violent hurricane. His body, never recovered. “Remember Me” was like a dirge, calling on the Lord to ensure their sacrifice would not be forgotten. In singing it, Granddaddy pays homage to all the men claimed by the sea while also carrying on his father’s legacy.

My grandfather, however, took a different career path. Drafted into the Army in 1945, he returned to Virginia after World War II to finish high school and attend college at Virginia Union University. In 1973, after a career in teaching and school administration, he became the first Black superintendent of an integrated school district in Virginia. And because of his contributions to education, Virginia University of Lynchburg awarded him an honorary doctorate of pedagogy in 2003.

While he did not become a fisherman, respecting his mother’s wishes of staying away from the treacherous waters, my grandfather—the consummate educator—found a way to engage with his father’s memory by teaching the public the historical value of these songs. “The average individual doesn’t know about the fish that are in these waters, and so the public asks lots of questions,” he said. “I imagine I was perfect for this.”

Elton Smith, Jr., the son of a fisherman lost at sea, and described by scholar and granddaughter Maya Angela Smith, right, as “a consummate educator,” has dedicated his life to preserving the sea chanteys of Black fishermen. Photo by Emily Smith.

And he was, telling the stories of African Americans who worked the seas. As I reflect on the recent surge of interest in sea chanteys (earlier this year, Scottish musician Nathan Evans’s performance of one quickly garnered more than 1.8 million views on TikTok), I’m struck by the assumption that this is primarily a white British folk tradition. According to Pomona College music professor Gibb Schreffler in a revealing article on chanteys, however, “the epicenter of the chanty song genre was not Great Britain, as is sometimes imagined, but rather America—or, more precisely, the western side of the ‘Black Atlantic,’ rimmed by Southern U.S. ports and the Caribbean.” The work of the Northern Neck Chantey Singers and groups like them is thus crucial for expanding our understanding of this musical genre because it decenters whiteness and allows for the diversity inherent in the chantey tradition to shine through.

In fact, chanteys are a global phenomenon with highly localized inflections. While all the songs revolve around work at sea, different regions have different music and words. Even the chanteys specific to menhaden fishermen boast a wide variation. “In North Carolina, they have some of the same songs but the music is a little different,” Grandaddy Smith explained. “In Virginia, the lyrics talk about specific bodies of water such as Chesapeake Bay or the Rappahannock River. In New Jersey, fellows would come up with music to fit that particular water.” These chanteys provide us with a geographical snapshot of what life was like for Black menhaden fishermen.

For my grandfather and people like him, these songs represent more than a history of cooperation, nostalgia, and resilience among fishermen. They are also more than the latest online fad helping people survive the isolation that a global pandemic has wrought. They represent a valuable, if little-known, aspect of Black cultural history.

Unfortunately, the Northern Neck Chantey Singers have not performed since early 2020. The COVID pandemic is partially to blame, but the aging of these cultural stewards represents an even greater challenge. All of the current members are in their 90s. “I enjoyed going out of state. I miss it a lot,” my grandfather lamented, “but I’m too old now. Life on the road is difficult these days.”

It is unclear what will happen to the group once the world returns to some semblance of normalcy. But given how very few groups exist that perform African American maritime folk music, if the Northern Neck Chantey Singers disband, it would be a major cultural loss.

Send A Letter To the Editors