The singer Jacek Kaczmarski, pictured here in a still from a 1986 documentary, was a hero to Polish people around the world. Courtesy of CITIZENS (1986) by Richard Ware Adams | Cinema Guild.

A microphone on a stand; a man with a guitar. The waiting audience is restless, shifting in seats as he tunes his instrument. He speaks one word—Kołysanka, lullaby in Polish. The audience settles, a few beats of silence pass. He begins with a quiet musical introduction, simple, soothing.

And then he sings.

The song is about children who walk round and round the yard of an orphanage, but are not orphans. One watches as his father is taken away from their home in shackles. Another wants to write a letter to her parents in an internment camp as she wonders: Does anyone know where I am?

When he finishes, the audience erupts into boisterous applause that morphs into synchronized clapping. The man leans into the mic: “I have a few songs left. Shall we leave this clapping till the end?” The audience laughs and cheers. “Noooo!” someone shouts. He tunes his guitar, clears his throat, and begins another song.

The year is 1983. The Cold War is still very cold, though U.S. President Ronald Reagan is a few years away from bossing the Soviet president about tearing down a wall. Men at Work’s “Down Under” and Culture Club’s “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me” are at the top of the U.S. charts. The Police will soon embark on their final official tour, with openers Joan Jett and A Flock of Seagulls.

This auditorium—at a community college on Chicago’s north side—is smaller and plainer than the ones The Police will play. Just 300-some seats, each filled for the first of four concerts organized by and for Polish-American activists, who have come to hear this performer and his acoustic guitar: Jacek Kaczmarski, the beloved bard of Solidarity—Poland’s massive social justice movement, nearly 10-million strong.

Born in 1957 in Warsaw to an artist couple, Kaczmarski studied polonistyka—historic and modern Polish language and literature—at the University of Warsaw in the 1970s. While still in school, he performed in cabarets, writing ballads that, through references to Polish history and art, commented on oppressive communist politics and restrictive policies.

Like any non-state-sanctioned artistic expression in an authoritarian country, Kaczmarski’s work carefully threaded the line between open critique and coy allusion. His ballads were filled with true stories of heroism that celebrated Polish resistance and heart. It was the exact opposite of the communist regime’s approach, which sought to depress national pride, and maintain control, by lying and casting blame.

Kaczmarski’s audiences loved him, and he soon began giving solo performances in private clubs and homes to avoid the scrutiny of the censorious government. He graduated in 1980, the same year that the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union, also known as “Solidarity”—whose membership included nearly one-third of Poland’s population—was officially recognized by Poland’s government as an independent trade union, the first of its kind in the entire Soviet Bloc. Kaczmarski too was a member and regularly played at Solidarity events. His ballad “Mury” (“Walls”) became the movement’s unofficial anthem, regularly chanted at protests. Supporters scrawled its lyrics on government buildings and park benches.

The movement was led by electrician Lech Wałęsa and welder Anna Walentynowicz, shipyard workers in Gdansk. Both were members of anti-communist, underground trade unions in the 1970s, which staged strikes and called for workers’ rights reform. In the summer of 1980, the communist government increased already high food prices, and the country erupted into a series of labor strikes. These accelerated when Walentynowicz, who edited an underground newsletter, was fired for her open criticism. She was five months from retirement, which meant she wouldn’t receive any benefits. In response, shipyard workers staged a strike demanding she be reinstated at work.

Although the shipyard caved within days, the workers kept striking—calling for higher pay, improved working conditions, and civil rights, including the freedom of expression—until the end of August, when the government formally recognized Solidarity. The union soon also received statements of support from the U.S. government and the Vatican.

Solidary continued its activism. But by the end of the year, the communist government had had enough. On December 13, 1981, nearly 2,000 military tanks began rolling down Polish streets, soon joined by thousands of combat vehicles and 100,000 members of the militia and secret police.

Ultimately, around 5,000 Solidarity members were arrested and put into detention cells. Their children were placed into orphanages, becoming orphaned non-orphans. TV and radio stations went silent. Borders were closed. At 6 a.m., the official state Polish Radio declared martial law. The days that followed were violent and bloody. A Solidarity-organized protest at the Wujek Coal Mine ended with thousands more arrests, beatings, and shootings, and multiple deaths. The youngest casualty was 19 years old.

Kaczmarski was abroad when martial law was announced. That October, he had begun touring with a French exhibition about Solidarity. Like many Poles around the world, he obsessively scoured for news as the strikes and arrests and deaths continued. And he kept performing, which is what brought him to the United States. One of his first stops was New York, where he met filmmaker Richard Adams.

“Our nation wants to create its life based on its own history,” Kaczmarski told Adams in 1982, after a performance in Brooklyn, for the documentary Citizens for Solidarity. “Not history as told by communist propaganda.”

Adams was deeply moved by the music’s complexity, and its message. “I felt that Kaczmarski’s singing had an intellectual, historical, moral and purely verbal richness that made American songs sound like jingles,” he told me, in a recent interview.

After New York, Kaczmarski came to Chicago for a sold-out concert series where he worked through an extensive set list of ballads written both before and after martial law. The pre-martial-law ballads dipped in and out of 19th- and 20th-century Polish history, presenting the Polish heroism often absent from post-World War II communist history books. The more recent ballads focused on the present, and were even bolder: mocking the communists, despairing the hopelessness of seemingly never-ending oppression.

“Sen Katarzyny II-giej” (“Catherine the Great’s Dream”) presents the love/hate affair between the voracious Russian czarina and one of her favorite lovers, Polish king Stanisław August Poniatowski. Kaczmarski’s baritone lowered to a guttural growl as he relished his way through the bawdy lyrics: “I need a lover as big as the [Russian] empire / who’d take me the way I give my all.”

In “Raport Ambasadora” (“The Ambassador’s Report”) a Polish nobleman protests the first partition of Poland in 1783: “‘Traitors!’ some shouted, but who to whom?…Win whatever you can win!” Kaczmarski spit out each and every syllable, then shifted to draw out a long vowel.

In “Listy” (“Letters”) Kaczmarski sang about the Cuban poet Armando Valladares, imprisoned by Castro for decades. “When I wrote this song, his case seemed hopeless,” Kaczmarski told the audience that night. “But that spring he was freed. This song is about waiting, and hope.”

He also sang what he called “a love letter” to the Russian actor and poet Vladimir Vysotsky, whom he’d met in 1974. Their lives came to have multiple chilling similarities, including early deaths.

And then, “Mury,” initially written in 1978, about the walls that can surround artists and their creativity—and by 1981 an anti-communist anthem for Poles everywhere. The Chicago audience sang along: “The walls will fall, fall, fall, and bury the old world.”

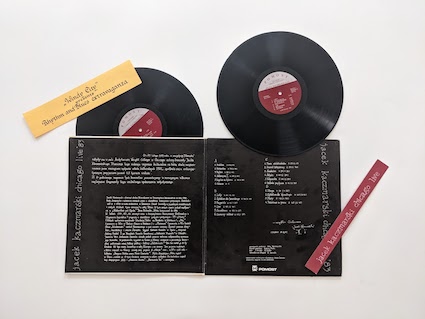

The plain black album cover for the concert recording of Polish singer Jacek Kaczmarski’s 1983 performance in Chicago was designed to evade confiscation by government authorities. His music delved into Polish history and criticized Communist oppression. Courtesy of Justine Jablonska.

Each of Kaczmarski’s concerts in Chicago was recorded for a double vinyl record album. My dad supervised the recording in a sound booth above the balcony; he and my mom were part of the Polish American activist group that organized the concerts. The album cover was black with a blank, white rectangle; the back completely white. No writing on the cover, representing the communist censorship that sought to muzzle Kaczmarski (in the autumn of 1981, the Soviet embassy in Poland had issued an official statement denouncing the “anti-Soviet” nature of Kaczmarski’s rhetoric).

The spare design would also help the albums slip past customs: his music was anathema to the communist authorities monitoring all incoming shipments during martial law. Hundreds of these albums would make their way to Poland over the next few years, accompanied by a fake liner: “Windy City” presents Rhythm and Blues extravaganza.

My brother and I met Kaczmarski that night in Chicago in ’83, ushered backstage during the act break by our parents. We solemnly presented the singer with a crayon drawing we’d labored over earlier that day: a brick wall, tall on one side, crumbling on the other. Above a stick figure wearing glasses and holding a guitar, I’d printed MURY in my childish hand. Kaczmarski took in the drawing for a few moments, and thanked us.

Kaczmarski kept touring. Anti-communist protests continued. Solidarity kept at it. Until April 1989, when the Round Table Talks officially ended communist rule in Poland. In November 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. And at the end of 1991, the Soviet Union dissolved.

Kaczmarski spent the rest of his life traveling, and settled in Australia for a while. He regularly returned to Poland but never lived there again. He drank heavily, alcoholism an ever-present demon, and in his mid-40s, was diagnosed with throat cancer. After a tracheotomy, he lost his voice, and by early 2004, could no longer speak. He died in April 2004, at the age of 47, and is buried in Warsaw.

My parents still have the master tapes of the Chicago concert recordings; they’ve never been digitized or shared, beyond the albums that were shipped to Poland. My copy of the record plays perfectly to this day. It’s a treasured possession, a time capsule. In the recording I can hear my mom laughing at something Kaczmarski has said. I know that somewhere in that applause, my brother and I are clapping. I have no photos or videos from the concert. But I have this record.

I reach to it in times of turmoil and uncertainty. The album reminds me that dark times come, and dark times go—as long as brave people exist to speak the truth. I recently watched a short clip of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s film Blind Chance, from 1981, about a character who, in one of three alternative storylines, becomes a member of the Polish opposition movement. Kaczmarski appears as himself in a short cameo, singing “Nie Lubie” (“I Hate”) at an underground Solidarity meeting.

He looks very young, very intense. “I hate myself when I feel fear / When I look for excuses for the wicked,” he sings. His lyrics are sharp and defiant, an eternal cry for justice in the face of tyranny.

Send A Letter To the Editors