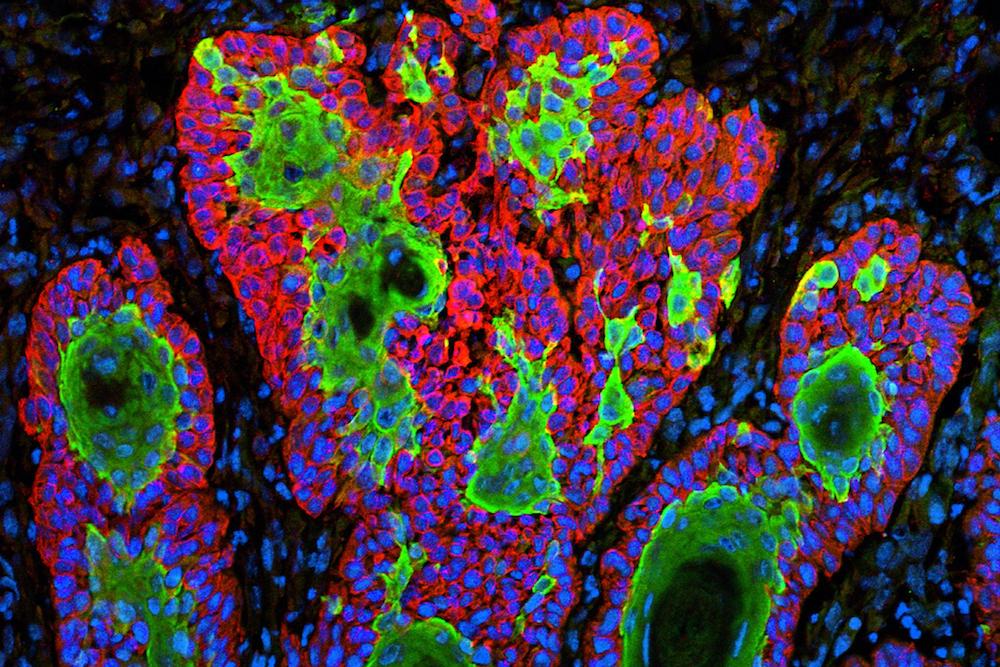

Uncontrolled growth of cancer cells in a form of skin cancer called squamous cell carcinoma. Courtesy of ZEISS Microscopy/flickr/Markus Schober and Elaine Fuchs, The Rockefeller University, New York, N.Y. Part of the exhibit Life:Magnified by ASCB and NIGMS.

An itchy, oozing little sore at the top of my right ear had me mildly concerned.

“I think I might have gotten a spider bite while sleeping,” I told the dermatologist.

He took one look and shook his head. “I’m afraid not.”

It was July 15, 2020. That same day, 971 people in the U.S. reportedly died of COVID-19, which, for the moment, put my ear nuisance in perspective. But what at first appeared to be an insect bite, and then an easily cured case of skin cancer, would rapidly progress to critical stage 4 metastatic cancer.

Developing stage 4 cancer is bad; getting that diagnosis during a pandemic is even worse.

California had gone into lockdown the previous March, making even a simple trip to the dermatologist an adventure in pandemic protocols.

Even a recognized killer like cancer had to make way for COVID. The first two deaths attributed to COVID-19 in the U.S. came in early February 2020; by year end, COVID was listed as being responsible for claiming 345,323 American lives. That put COVID in third place for the year as a cause of death behind cancer, in second place, which killed 598,932 in 2020. (Heart disease remains the number one killer.)

As I waged my cancer battle in the shadow of COVID, I was reminded of the title of the Gabriel García Márquez novel Love in the Time of Cholera, and one quote in particular: “Be calm. God awaits you at the door.”

The Diagnosis: Part I

When repeated applications of Neosporin didn’t seem to help the spot on my ear, I called my internist. It would take weeks to get an office appointment, and in-person visits were discouraged because of COVID. The office aide offered a much sooner video consultation with my doctor, which she assured me would work fine for my issue.

On June 16, my internist appeared as a grainy, jumpy image on my computer screen. I turned to show him my ear, but he couldn’t see much. “You should have come in,” he said. He advised me to bring the matter up with a dermatologist.

As it happened, I had a dermatologist appointment for a routine skin examination in about a month. Actually it was a rebooked appointment, which I had gotten only after agreeing to see a new doctor. The first appointment, scheduled two months earlier, had been canceled by COVID. Perhaps if I had kept that first routine appointment, a minor abnormality might have been spotted on my ear and treated, and I would have avoided everything that followed.

When I finally arrived at the dermatologist’s office, I was met by an assistant posted outside the front door who took my temperature and asked if I had any COVID symptoms or a positive COVID test. This would be the standard procedure for doctor visits for the coming year. Once inside, the doctor gave my ear the disapproving look and then took a chunk out of it for a biopsy. It came back positive for squamous cell carcinoma.

The diagnosis was bad, but apparently not too bad. It was worse than basal cell carcinoma, one of the easiest cancers to cure, but not as bad as melanoma, the most dreaded diagnosis. If caught and treated early, squamous cell carcinoma has a 95 percent cure rate. The key was early detection and action. I had already lost several months.

The Treatment: Part I

The cure was Mohs surgery, which involves cutting out the skin cancer and some surrounding tissue to establish “clear margins” with no cancer. “Don’t worry, you’re not going to die,” the surgeon told me at our first meeting. I had never considered death as a possibility, and her reassurance had the opposite effect.

I arrived for my surgery on July 27. My wife, Susan, waited in the car in the parking lot with Bowie, our 11-pound fluffy poodle mix. The surgeon sliced some skin off my ear, put a patch over the incision, and had me wait in the car for my results. The lot was full of cars with wounded people waiting for similar call backs.

The first cut didn’t do the trick, so I had to go back inside a second time, and then a third. The parking lot slowly emptied until we were the last car left. But finally, after the third cut, the surgeon declared, “You’re cancer-free.”

I diligently followed the care instructions for the cavernous cut on my ear, but it seemed slow to heal. It had turned milky in color. Susan didn’t like the way it looked. I called the doctor, who said it was normal. About a week later, I began to feel discomfort on the right side of my neck just below my wounded ear. It got worse overnight, turning into a searing and stabbing pain with neck swelling.

The Diagnosis: Part II

When I reached the surgeon by phone, she diagnosed it as an infection at the surgery site that drained down into my neck. This sometimes happens, she explained. She prescribed an oral antibiotic and an ointment for my ear. Sure enough, I began to feel a little better and the swelling subsided somewhat. As a precaution, she referred me to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist and surgeon for another opinion.

I saw him two weeks later. My neck still ached and some swelling remained. He said there was a very slight chance that the cancer had spread to the saliva gland in my neck, called the parotid gland, but this was extremely rare. He put me on another round of antibiotics.

The infection diagnosis was statistically reasonable. A cancer like mine spreads to another organ—metastasizes—in just 1-5 percent of cases.

Days passed. My ear wound refused to heal. My neck discomfort and swelling remained. “I don’t like the way this looks,” Susan kept saying.

Outside, COVID raged. We holed up at home, getting groceries and meals delivered and fearfully wiping all the surfaces with disinfectant. Inside my neck, my cancer was quietly creeping unchecked from the parotid gland to my lymph nodes.

One day, Susan developed a minor irritation in her nose, so she made an appointment with my ENT. They not only took her right away; they also let me join her in the examination room that day after we explained that I was also a patient. Up to this point, Susan had attended my appointments and diagnoses only via FaceTime.

This apparent lapse in pandemic protocol may have saved my life.

Susan’s issue was straightforward, and so the doctor turned to me to see how I was doing. Things were not getting better, I said. He took yet another look, reexplained the rare possibility that the cancer had spread, and suggested another week or so on antibiotics. Then, if my symptoms persisted, he would do a needle biopsy of the swollen area of my neck.

I was ready to accept that.

Not Susan. She had seen enough.

“Why don’t we do the biopsy now?” she said. While Susan watched, he jabbed me in the neck with a long needle and extracted several fluid samples. About a week later, we got the call: the cancer was in my neck.

What I had was a very fast-moving skin cancer that was intent on colonizing other parts of my body. If not for Susan, I might have lost several more precious weeks—and, I would learn, my life.

The Treatment: Part II

The new diagnosis changed everything. I needed major surgery, and it had to happen now—a stunning contrast to the wait-and-see attitude and in-office procedures of the previous few months. Within the hour of getting the biopsy results we had the name of a doctor at Stanford Health Care: Dr. Davud Sirjani, a highly regarded specialist in head and neck cancer surgery with particular expertise in the parotid gland.

Less than two weeks later, I was in Sirjani’s office in Palo Alto, 100 miles from our home in Monterey County.

Sirjani and two assistants crowded into the rather cramped patient room, with Susan patched in via FaceTime while she and Bowie sat in the car.

My cancer was exceptionally aggressive, he said. Initial tests indicated evidence that it had travelled beyond the parotid gland to the lymph nodes.

“We have one chance to get ahead of it,” Sirjani said. If it—stage 4 metastatic cancer—got to my lungs, he said, “There is nothing I can do.”

Sirjani bumped me to the head of the surgery line. He advised me that he would take off more than a third of the top of my ear and remove both my parotid gland and the lymph nodes on that side of my neck. The surgery would take about five hours and was fraught with possible complications. Nerves and muscles could be compromised; loss of feeling and movement were possible. I might have difficulty speaking and swallowing. And there was a chance that the surgery would not successfully remove all the cancer.

But all I could think to ask was, “I wear glasses. Will I still be able to wear them?” Sirjani said he would leave me a notch or flap of ear skin and tissue big enough to support glasses.

The day before surgery, we drove up to Stanford on Highway 101. The sparse pandemic traffic felt like a trip back in time. The pandemic lockdown was so strict that you weren’t supposed to travel outside your home county except for essential business. We checked into a nearby hotel; the lobby was eerily empty.

Before dawn on November 2, Susan dropped me at the hospital and went back to the hotel to wait with two friends who had come to support her. I probably should have been filled with trepidation. Instead, I was exceedingly calm and confident as I was sedated and wheeled into the operating room. The surgery lasted five hours.

I woke that afternoon in a hospital room bed, sutured on my ear and neck but unbandaged, and with a small drainage tube protruding from a hole in my neck to a little plastic bulb pinned to my hospital gown. Periodically emptying this bulb of pink fluid would be Susan’s unfortunate task over the coming days. The surgery had gone well, and after one night in the hospital, I was declared well enough to leave. My first night out, I slept half sitting up in bed, afraid of pulling the tube out of my neck.

Over the next week, I slept a lot and stumbled around the house with that drainage tube sticking out of my neck. At my follow-up a week later, Sirjani removed the tube from my neck and said the initial results of the surgery were very good.

He had cut off half my ear and removed about three pounds of tissue from my neck. He half-joked that he had pulled the skin on my neck so tight while putting me back together that I had gotten half a facelift. But one lymph node was not fully intact when he removed it, indicating the cancer could have escaped into nearby tissue. My anticipated radiation regimen would become more intensive as a result.

My five-days-a-week, six-week radiation course began a month later with the creation of my “mask,” a white plastic mesh covering formed to my head, neck, and shoulders. The radiologist drew target areas on my mask so technicians could aim the beams accurately. For treatment, I would don the mask and lie back on the radiation table, clamped in place. Then a technician, working from a secure booth, would line up the giant radiation wheel suspended on a mechanical arm above me and set in motion a program that had the device zap me in precise locations with precise doses.

In early December, Susan, Bowie, and I started our new routine. We would drive up to Palo Alto on Monday morning, stay in a hotel through Thursday night, and drive home Friday after my treatment. Radiation appointments were always completely booked, and I was repeatedly admonished not to be late to keep everyone else on schedule. COVID had the power to empty highways of traffic, but it could not slow down the cancer treatment assembly line.

My daily visits to a medical facility used by hundreds of workers and patients made the possibility of contracting COVID a constant concern. I masked religiously, washed my hands regularly, gave others a wide berth. In the radiation waiting room, seats were suitably distanced, but I eyed other patients warily, and they did the same. Anyone who coughed got a distressed glance.

Courtesy of the author.

But even as California became the epicenter of the post-holiday COVID surge, I stayed healthy through my last radiation treatment on January 15. I lost weight, and the radiation left me with what looked like a terrible sunburn on the right side of my neck and jaw, but that went away. Susan hung my radiation mask on the wall, adorned with several decorative lapel pins. It has the look of an odd piece of modern art, but one with special significance for us.

I spent the next months eating healthy, exercising, and trying to regain lost weight. On April 29, I had a follow-up MRI. The results were exactly what we had hoped for: no evidence of active cancer.

Returning to Normal

As radiation was eradicating the last remaining vestiges of cancer from my neck, scientists were completing their race to cure COVID. On December 11, the FDA approved the Pfizer vaccine. A week later, Moderna’s vaccine got the nod.

Susan and I got our first jabs on February 5 and the second on March 5. Businesses began reopening, and we ventured out to restaurants for the first time in nearly a year. We went to a dinner party for 10 at a friend’s house in May where all the guests had been vaccinated.

A curious pattern began to emerge in conversations. Questions about how I was doing invariably were followed by stories about someone else who had cancer. Suddenly, cancer seemed to be everywhere, or perhaps it always had been, but I had never really noticed before.

Susan ran into a friend on the street whom she hadn’t seen in a long time. The friend blurted out that she had been battling stage 4 cancer.

A friend related that both her parents died of cancer during the past year while COVID raged. So did her dog.

Another friend said she was glad to hear how well I was doing, and by the way, her mother had stage 4 cancer.

A work colleague’s wife had a setback in her battle with breast cancer.

A friend’s mother had ovarian cancer and was taking shark cartilage as an alternative treatment.

A close friend caught COVID while undergoing chemotherapy. She had to fight both metastatic breast cancer and COVID. She eventually died of cancer. At her request, I wrote her obit.

Before my diagnosis, Susan’s brother was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer that ultimately killed him. She was unable to travel across the country to be with him because of the pandemic.

I noticed that the mention of cancer triggers a similar reaction in nearly everyone: a reverential tone tinged with a sort of background fear. The universal message is that cancer can strike anyone and it is not a disease to trifle with.

What has been curious to me about COVID is that it didn’t garner the same level of universal respect. Almost from the start, some people questioned its ferocity and whether all the precautions were necessary—or worth the economic cost. Even free vaccines promising to cut the risk of infection rates by 90 percent have met resistance; according to polling, 1 in 5 Americans say they won’t get vaccinated. I wonder if some people would also resist a cancer vaccine. Having had a taste of the disease, I know I would be first in line.

Of course, a universal vaccine for cancer remains well out of scientific reach. There are more than 100 different types of cancer. I intend to keep a wary eye on COVID while striving to avoid another cancer encounter in the future. My new cancer strategy includes several lifestyle changes based on various recommendations: a plant-based diet, avoidance of sugar and dairy, more exercise, and mindfulness activities (I started qigong).

Pandemics come and go. Cancer abides.

Send A Letter To the Editors