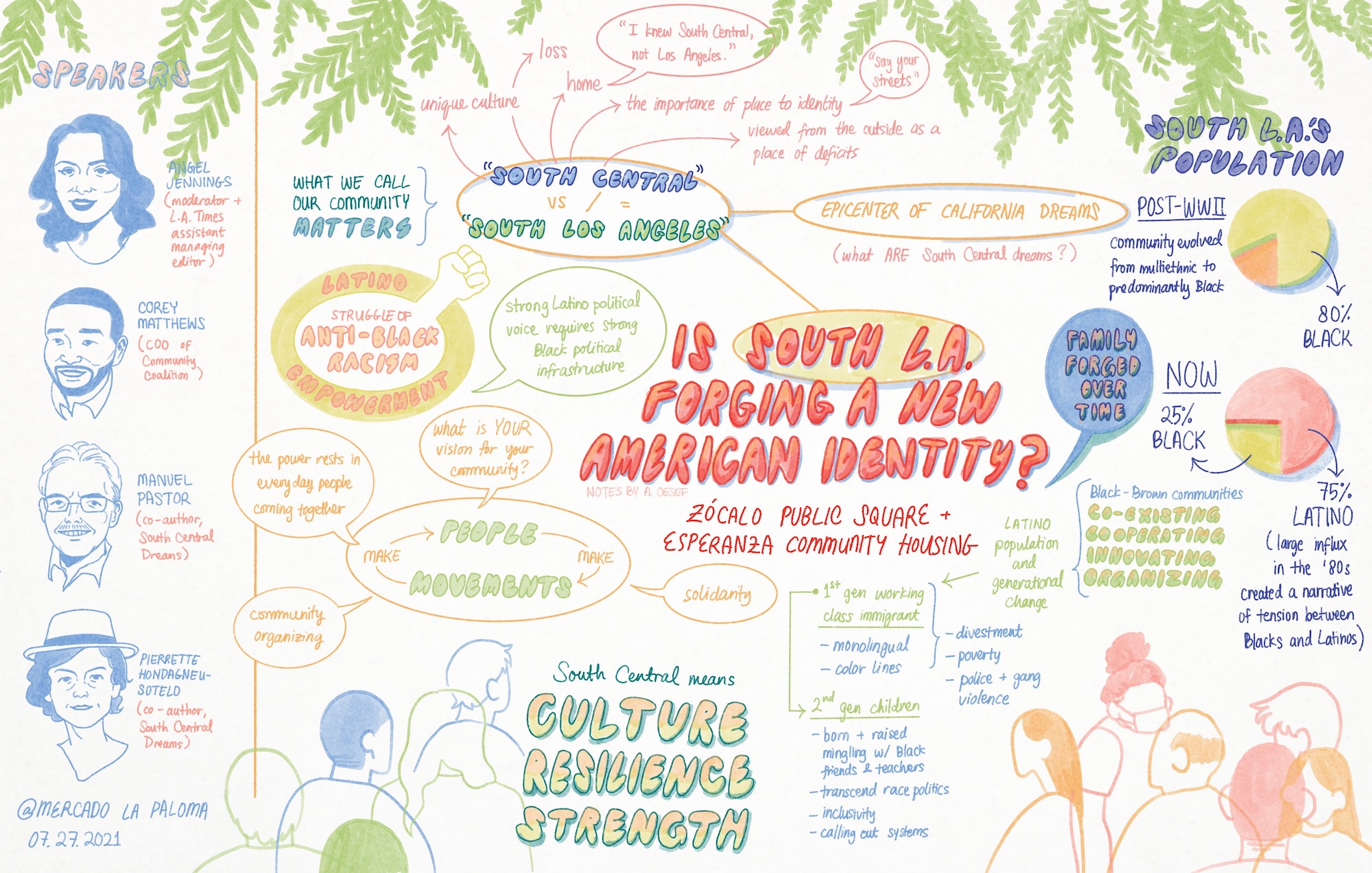

From left to right: Angel Jennings, Manuel Pastor, Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo, and Corey Matthews. Photo by Aaron Salcido.

Under the shade of Mercado La Paloma’s gold medallion trees, some 200 masked guests gathered to take part in Zócalo Public Square’s long-awaited return to in-person programming.

The open-air event, which also streamed live online, was produced in partnership with Esperanza Community Housing’s South Central Innervisions: An AfroLatinxFuturism, a free multidisciplinary arts festival being held at the mercado, a marketplace and community center in the Figueroa Corridor, this Saturday.

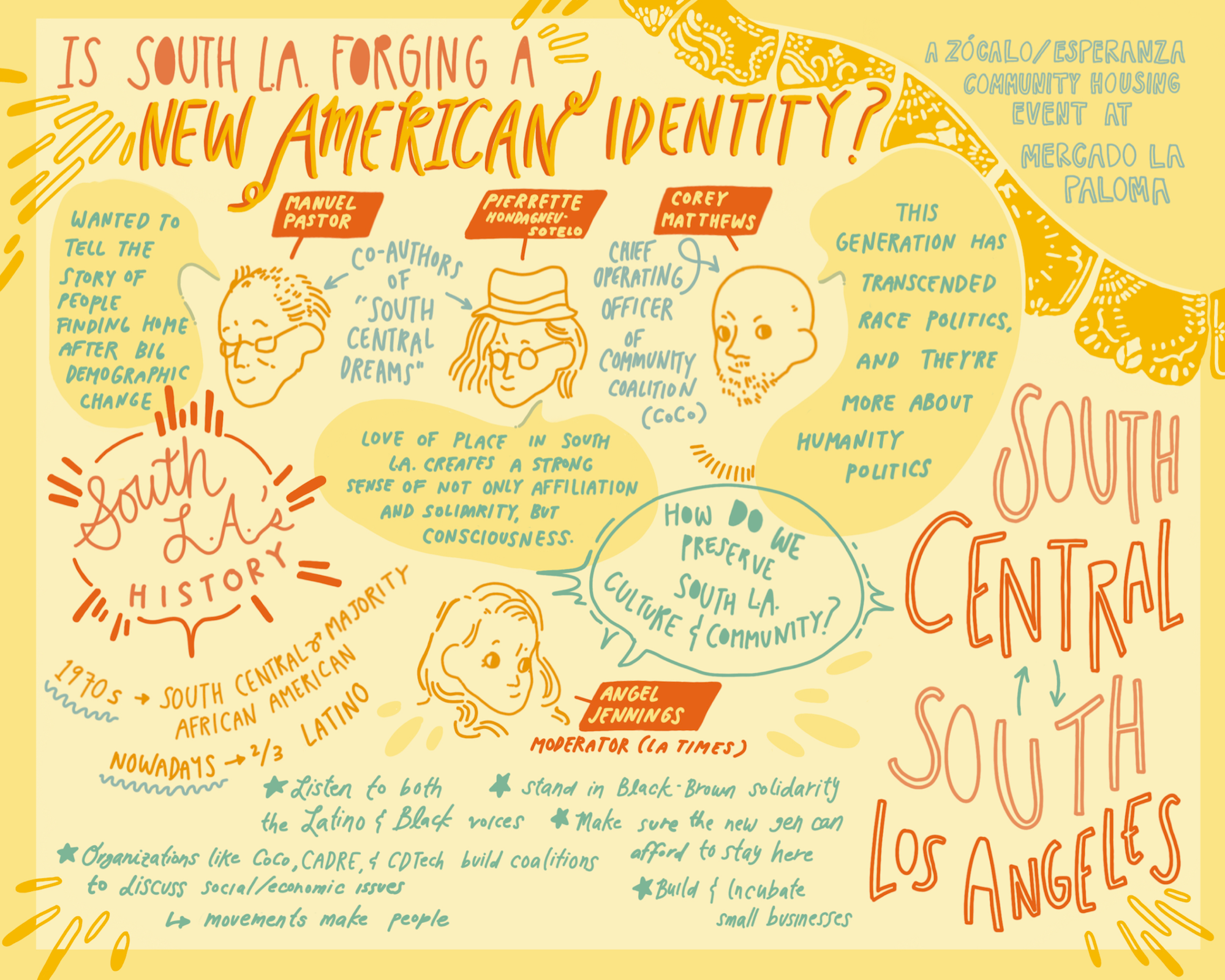

The question of the evening—“Is South L.A. Forging a New American Identity?”—offered a dynamic look at how place-based identity can build bonds of solidarity across racial and ethnic lines.

Before jumping into the conversation, moderator Angel Jennings, the Los Angeles Times’ assistant managing editor for culture and talent, explained why the panelists would be using the terms “South Central” and “South Los Angeles” interchangeably.

“You can’t talk about this region, this community, and this area without first giving it a name, and identifying and describing it,” said Jennings. Located on the ancestral and unceded territory of the Tongva people, said Jennings, this land has become “the epicenter of the California dreams for so many.” That includes African Americans, many of whose descendants came to South L.A. from the South during the Great Migration, and immigrants from Central and South America and their children and grandchildren, who’ve increasingly made it their home over the last four decades.

When it comes to South Los Angeles or South L.A., Jennings said, both names have legitimate claims to the space.

Panelists Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo and Manuel Pastor, USC sociologists and co-authors of a new book, South Central Dreams: Finding Home and Building Community in South L.A., which inspired the discussion, agreed, noting that even their title straddles both names. They interviewed some people, young and old, who Hondagneu-Sotelo said, consider South Central “a special term of endearment,” while for others, South L.A. feels more encompassing, especially among those who hadn’t felt included before. “In Watts, they felt very firm,” she added. “This is not South Central. This is Watts. There’s a particular pride in the uniqueness of the place.”

Visual notes by Amanda Oesef

Panelist Corey Matthews, chief operating officer of Community Coalition or CoCo, is a local himself, born and raised on 108 and Western. (He noted, and the audience agreed, that part of being from South Central is naming your streets.) Matthews recalled leaving home and returning to a place with a new name and new demographics. “In a lot of ways,” Matthews reflected, “I’m relearning and learning newly what South Los Angeles is.”

To tell this story of demographic change, Pastor looked to the numbers. In 1970, South Central was 80 percent African American, and around half of Los Angeles County’s Black population lived in the area. Today, South L.A. is two-thirds Latino, and only one-quarter of the county’s Black population lives there. This data offers “a sense of loss on the part of the Black population of this central place of meaning for the community—not just for people who lived there, but for all of Black Los Angeles,” said Pastor.

Amid this demographic transformation, academics and the media focused on the tensions between Black and Latino residents, but few scholars have revisited that narrative since. In their book, Pastor and Hondagneu-Sotelo explore how South L.A. today tells a different story: of how Latino and Black residents have come together and built community in this historically Black space.

What, asked Jennings, were the most surprising things that came out of their research, which included interviews with nearly 200 residents?

For one thing, they said, how central place can be to identity. “Latinos in South L.A. are different than Latinos in the rest of Los Angeles,” said Pastor. Beyond, say, a preference for hip hop over Ranchera music, second generation Latinos, they found, are steeped in the history of American apartheid and Jim Crow. “They’re very easily able to center the struggle of anti-Black racism even as they’re lifting up Latino empowerment,” said Pastor.

Another key finding centered around community organizing. The impact of South L.A. community organizing groups, including institutions like CoCo and Community Asset Development Re-defining Education (CADRE), has been widespread in forging coalition-building among Black and brown residents. “We often think people make movements,” said Pastor, “but movements also make people.”

Matthews agreed. “I’m really fascinated by this generation,” he said, noting that young people of color are coming together around issues that matter to them, whether it’s parks and green space, art, wellness, or entrepreneurship. CoCo’s South Central Youth Empowered through Action (SCYEA) group, for instance, held a teach-in in response to the rise of anti-Asian American hate crimes. “They felt it important to elevate [their] concerns and draw similarities between their experiences and their comrades that were of a different background,” he said. It was a marked contrast to his own experience as a young person. “That was something that we were not doing, at least not explicitly, and certainly not with language at the time,” he recalled.

Visual notes by Soobin Kim

The young people doing this work today with this capacious understanding of identity, said Hondagneu-Sotelo, are “South L.A.’s biggest asset.” They possess “love of place formed by these communities, formed by daily experiences, interactions with schools, sports teams,” all of which creates “a strong sense of not only affiliation and solidarity, but consciousness.”

This has larger implications for the nation as a whole, Pastor said. “Historically, South Central has been looked at from the outside as a place of deficits. As a place of economic challenges. I don’t want to minimize all those,” but he said, “South L.A. is a model of what could be done with good community organizing, power building, and coalition building.”

The panelists also answered questions from audience members participating in the virtual chatroom, including one around what such coalition-building demands.

Pastor cited “frank and honest conversations around differences,” recalling a Q&A from a panel he was on several years back with CoCo founder and U.S. Representative Karen Bass.

Pastor recalled a “young Black man who said, ‘You know, I used to like Mexicans, I just don’t like these new Mexicans’—by which he meant Central Americans.” Another, older Black man in the audience offered his own generalization: “‘Latinos like to work.’” These “impolite, impolitic” statements would never come up in an academic setting, noted Pastor, yet they started a difficult, meaningful conversation. “And out of that real and honest conversation grew a Black-brown alliance to support the retrofitting of city buildings, pipelines for jobs for Black and brown people,” he said.

Before the conversation wrapped, Jennings asked the panelists: What should we be thinking about as we reimagine the future around South L.A.?

“Are we building a South L.A. that will allow our young people to buy here, live here, and stay here?” Matthews asked.

Hondagneu-Sotelo and Pastor agreed, addressing displacement concerns. “Home,” said Hondagneu-Sotelo, “is a key aspect of the book, and the looming danger is, can South Central continue to be a home for those who are currently here—who’ve been here for several generations?”

Send A Letter To the Editors