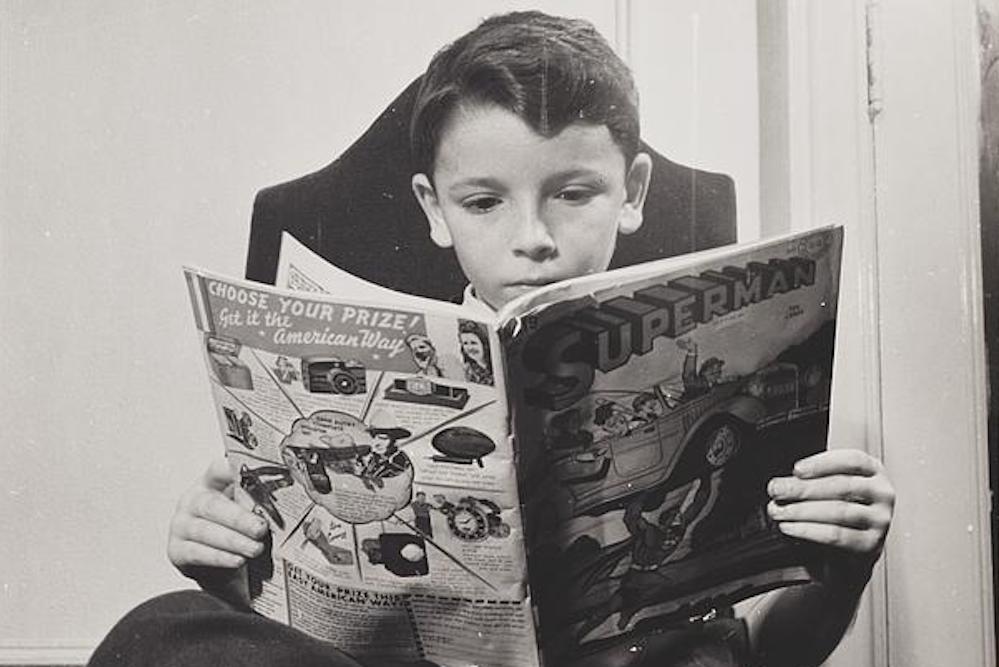

In the 1950s, the increasing fear that comic books would corrupt young people led to censorship of the medium, public burnings of comic books, and a Senate hearing. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The story of QAnon’s violent extremism is often told as one of partisan polarization. We tend to focus on the most outlandish parts of the far-right conspiracy theory—which falsely claims former presidential candidate Hillary Clinton was at the center of an international Deep State pedophile ring tied up in murder and occult ritual, and that would eventually be exposed and punished by Donald Trump. But in doing so, we miss how it is also fed by something so universally accepted that we don’t acknowledge how modern it is: our values about children and childhood.

Modern childhood is less than 150 years old, and so is our way of talking about children as being fundamentally different from adults. This care and concern for the young has flowered in a variety of ways in modern society, and emerges in a mix of public emotions and policy advocacy. But sometimes, as with QAnon, it can also lead to outright conspiracy theorizing. We can, in turn, learn a lot about QAnon—and our vulnerability to conspiracy theories—if we trace its focus on children to its roots.

Our cultural training to be outraged over threats to childhood emerged in the decades after the Civil War, as mechanized industry, growing cities, and American childhood collided, literally. Children playing in streets were no match for motorized vehicles. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, American city newspapers regularly reported children killed by streetcars and automobiles, and by the time the 1890s rolled around, outrage over children’s deaths led social reformers in Chicago and other cities to open private playlots and urge city leaders to build public playgrounds so children could play off the streets. Children on the streets were not a new concern. But setting aside public space so children could play safely? That was new, and this early advocacy reflected a changing attitude toward childhood, one that posited that it was a unique life stage requiring special protection.

The growing public stance of care and concern for the young was broader than public safety regulations, extending to morality concerns, such as in the mid-1950s when psychiatrist Fredric Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent. The influential text argued that both violence and sexually suggestive images in comic books led to juvenile delinquency. Wertham’s argument fit into a postwar pearl-clutching panic over so-called crime comics, stoked on the national stage by Senator Estes Kefauver, whose hearings on juvenile delinquency fed local efforts to censor mass culture, and presumed that parents were losing control over their children.

This kind of rhetoric has been recycled, decade after decade, focusing on different issues and with different cadences, but always highlighting putative dangers to childhood and youth. Arriving a decade after Wertham, and feeding into a backlash to desegregation, bilingual education, and sex education was conservative journalist John Steinbacher’s, 1970 bestseller The Child Seducers, which started with a controversy over sex education in Anaheim, California, and spun a tale of 50 years of worldwide conspiracy that would first provide “sex instruction” to children and then somehow turn libertine impulses into the destruction of America.

The spinning of conspiracy theories coexisted in each decade with a more serious focus on policy that addressed children’s needs. Importantly, both were expressions of the modern idea of childhood. Take the work of lawyer Marian Wright Edelman, active at the same time as Steinbacher, who founded the Children’s Defense Fund. An expert in both claiming the moral high ground and advocating specific policies, Edelman began with a 1973 report on children denied schooling, and moved on to almost every material issue touching children: poverty, education, healthcare and beyond.

The increased overlap between serious concerns and conspiracizing may have been an artifact of the Baby Boom. Children born at the peak of the Boom graduated high school in 1974. So, of course, public attention focused on this generation—not just Steinbacher’s ravings and Edelman’s serious concerns but panics and arguments over the effects of divorce, the trends of teenage pregnancy, advertising on children’s television, misbehavior in high school, and more. But the aging of the Baby Boom after the 1970s just meant that they became parents, dominating the discourse of childhood from a different perspective, bringing their experience as postwar consumers, including as consumers of their own parents’ concerns.

As Boomers were becoming parents, and dominating American demographics as young adults, President Ronald Reagan helped promote concerns about strangers and child kidnapping. Pictures of missing children appeared on milk cartons, thanks to private milk distributors choosing to contribute to the public discourse about stranger danger. Private companies encouraged parents to fingerprint their children, just in case they became victims of gruesome crimes.

As Paul Renfro describes in his new book on the era, Stranger Danger, this moral panic obscured the fact that the vast majority of children reported as missing were (and today remain likely to be) either teenage runaways or taken by noncustodial parents. Rather, what this campaign really did was obscure the more probable dangers of domestic violence and sexual abuse perpetrated by adults already known to their victims.

The birth of the internet only added a new layer to these concerns: the danger could come from anywhere in the world, at any time of the day. In the 1990s, parents could read fearmongering headlines like “Youngsters Falling Prey to Seducers in Computer Web” or “Cyberporn … Can We Protect our Kids—and Free Speech?” While most child abuse is local, with the abuser well-known to the child and family, these stories suggested that emails and chat forums would connect children and youth directly to strangers who would abuse or kidnap them, and the initial connections could happen in their own bedrooms. In turn, this public panic has sent policymakers of all political stripes scrambling after boogie monsters—such as with the Communications Decency Act of 1996, an attempt to criminalize indecency online that the Supreme Court struck down the following year as unconstitutionally vague.

The so-called bathroom bills of recent years contain one of the most crucial tells about the rhetoric of childhood, or the pairing of rhetoric about precious children with public rage. Driven by legislators in North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Georgia, bathroom bills intend to closely regulate which children go in which school bathrooms—just like states mandated racial segregation in schools and public bathrooms a century ago—and they target transgender children in the guise of protecting other children. This outrage was never over the safety of all children’s bodies but the need to decide which bodies belong where.

Every decade or so, we have an opportunity to refocus on what matters most to children instead of what triggers adults. But this long history of public panic shows that we have not redirected our outrage. We are still too easily distracted by our passionate promises to childhood. Not children, but childhood in the abstract, most commonly symbolized by white children, who are portrayed as being pure.

An ugly symmetry of modern American childhood pairs public outrage on behalf of children with public and publicly acceptable rage at children. Here childhood is protected, childhood is sacred, childhood is something to rage about if threatened. But not every child. We must remember: In 1955, the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till. In 1989, Donald Trump placing newspaper ads demanding the return of the death penalty in the middle of the Central Park Five case involving false prosecutions of a 16-year-old, two 15-year-olds, and two 14-year-olds. In 2014, police killing Tamir Rice at 12. This spring, Adam Toledo, 13.

Until we start to resist our cultural training, we will continue to be triggered into public outrage, which serves our feelings as adults, not our responsibilities to real children. Our vulnerability to that outrage did not expire with the Trump administration, nor did our capacity to be distracted by moral panics, nor our ability to simultaneously proclaim that we would protect childhood in the abstract while also raging at living, breathing, individual children.

Already, the QAnon conspiracies of 2020 have morphed; we hear fewer nonsensical allegations in public about Hillary Clinton and more about COVID vaccines, and bills in multiple states to restrict how we teach about the history of racism in the United States.

But a good portion of the conspiracizing in 2021 still revolves around children, because of that long history of modern childhood ideology and training for outrage. This readily available passion is part of modern public discourse—and it is not just among QAnon adherents. It is all of us, vulnerable to mistargeted outrage that distracts us from larger, systemic dangers to children.

Send A Letter To the Editors