Horace Kallen envisioned America as “a multiplicity in unity, an orchestration of mankind.” Courtesy of Craig James/Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

More than a century after Jewish American philosopher Horace Kallen developed the concept of cultural pluralism in 1915, it has never been more important. In the simplest terms, cultural pluralism is the idea that diversity is the true genius of American culture. Or as Ralph Ellison put it in 1961, “I believe in diversity, and I think the real death of the United States will be when everyone is just alike.” The concept is rooted in the belief that America is at its best when it welcomes immigrants and allows them to cultivate their distinctive social worlds and create a vivid mosaic of interacting parts. Cultural pluralism visualizes American culture as an ever-changing process rather than a fixed product and America as a constantly emerging nation whose polyglot nature has always been its greatest strength.

Cultural pluralism materialized as a forceful response to the white racism and rabid xenophobia that erupted during the years surrounding World War I. Understanding how a group of men and women confronted such bigotry and persecution more than a century ago can provide a map for thinking and practice as we struggle to respond to these same forces in the present.

A wide array of intellectuals and activists developed versions of cultural pluralism with Kallen, including social worker and activist Jane Addams, philosophers William James, Josiah Royce, and John Dewey, radical journalists Randolph Bourne and Max Eastman, Norwegian American novelist Ole Rolvaag, Jewish intellectuals Judah Magnes and Jesse Sampter, and Black writers W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke. Their perspective was a sharp contrast to Presidents Theodore Roosevelt’s and Woodrow Wilson’s demands that immigrants and minorities fit into a uniform American mold or merge into an obliterating melting pot, as popularized by Jewish British playwright Israel Zangwill’s 1908 play, The Melting Pot.

Seven years after Zangwill’s play appeared, Kallen coined the term “cultural pluralism” in an essay titled “Democracy versus the Melting Pot.” Born in 1882 in the German province of Silesia, Kallen immigrated with his family to Boston in 1887. He grew up in a poverty-stricken household, the oldest child in a large family overseen by an authoritarian father and Orthodox rabbi who expected him to follow in his footsteps. He rebelled, heading to Harvard instead, where he became a favored student of philosophers William James and Josiah Royce, whose respective visions of a “pluralistic universe” and a “wise provincialism” left a deep impression upon the young scholar. Kallen had a long and eventful life. From his first teaching position at Princeton, where he was fired in 1905 for discussing Judaism and atheism in the classroom, to his distinguished tenure as a founding member of the New School for Social Research in New York between 1919 and 1974, Kallen was a multi-talented and influential figure.

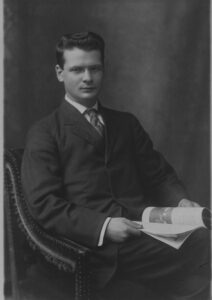

Horace Kallen circa 1908 (Image courtesy of author)

The most productive stretch of Kallen’s career occurred during the years he lived and taught at the University of Wisconsin in Madison from 1911 until 1918. This was his first exposure to life west of the Hudson, and his experiences living in and traveling throughout the youthful, culturally diverse Midwest were essential to the birth of his pivotal idea. His exposure to vibrant immigrant communities in Chicago and other Midwestern cities as well as encounters with ethnic enclaves across Wisconsin’s rural landscape provided living examples to push back against the militantly unifying melting pot concept. He was an engaging young man, and personal interactions with a range of Midwestern intellectuals as varied as novelist Theodore Dreiser, Nordic racist Edward A. Ross, and progressive statesman Robert La Follette added texture to his emerging idea. This multitudinous Midwestern experience, combined with the approach of war and anti-immigrant hysteria, precipitated Kallen’s 1915 vision of a polyglot America as a vast symphony orchestra, as “a multiplicity in unity, an orchestration of mankind,” an ideal that stood as a peaceful alternative to the toxic nationalism that had engulfed Europe and threatened the United States.

Similar imagery had been used long before, most significantly by social worker and activist Jane Addams who, based upon her work at Hull House in Chicago, depicted the nation as a grand chorus of many voices and promoted “cosmopolitan neighborhoods” as seedbeds of diversity as early as 1892. Indeed, the hope of truly “achieving our country,” as philosopher Richard Rorty wrote in 1999, and of realizing a society where “individual life will become unthinkably diverse and social life unthinkably free,” had been expressed in various forms across much of the 19th century. A deep-seated belief that America’s true genius lay in its capacity for endless diversity had, for example, been expressed in Frederick Douglass’s 1869 speech, “Our Composite Nationality,” where he envisioned the United States as “a country of all extremes” whose “races range all the way from black to white, with intermediate shades which no man can number.” This prophecy—also projected by Emerson, Melville, and Whitman—held up America’s mixed and piebald character as its greatest strength and highest achievement.

Several generations later, Kallen’s vision of a multitudinous America struck a chord and sparked a widespread debate. Within a year of Kallen’s landmark essay, his close friend, radical journalist Randolph Bourne, projected an image of the United States as “trans-national America” and “a cosmopolitan federation of national cultures, from which the sting of devastating competition has been removed.” With the nation’s entry into war in late 1917 and in response to demands for absolute loyalty—and persecution of those who refused to kneel and kiss the flag—a growing number of pluralists joined Kallen and Bourne in extolling diversity and decrying the menace of unblinking obedience to the state.

This rabid nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiment persisted after the war ended; in 1919, President Wilson proclaimed that “any man who carries a hyphen carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic.” In contrast, philosopher John Dewey wrote in 1916 that “the genuine American, the typical American, is himself a hyphenated character.” Meanwhile, Norwegian American novelist Ole Rolvaag believed that immigrants and their children needed multiple roots to flourish in a new land, warning in the early 1920s that due to “the highly praised melting pot…America is doomed to become the most impoverished land spiritually on the face of the earth.”

Kallen was at the core of this pluralist conversation, but it is important to recognize that his original theory was streaked with flaws, the darkest being its narrow frame of reference. Although radical for his time, Kallen’s early focus on European-based ethnic groups at the expense of non-white African- and Asian-based groups constituted a serious myopia shared by many of his otherwise clear-sighted contemporaries. As historian Mike Wallace succinctly put it in 2017, “Kallen’s cultural pluralism… stopped at the color line.” Wallace’s statement underscores fellow historian John Higham’s criticism that “the pluralist thesis from the onset was encapsulated in white ethnocentrism.” But by the 1950s, his theory would evolve far beyond white ethnocentrism and the color line, thanks to Kallen’s nearly life-long interracial friendship with fellow philosopher and founder of the Harlem Renaissance Alain Locke, who deserves credit as co-creator of cultural pluralism.

Alain Locke circa 1908 (Image courtesy of author)

In 1906, 20-year-old Locke was a student in a class at Harvard taught by 24-year-old Kallen. They exchanged ideas about cultural identity and diversity, and in the process, as Kallen recalled, “The formulae, the phrases developed—‘cultural pluralism,’ ‘the right to be different.’” A year later, their paths crossed again at Oxford, where Locke was the first Black Rhodes scholar and Kallen was doing post-doctoral research. In England, their friendship and cultural pride deepened as Kallen became increasingly aware of anti-Semitism and Locke experienced double prejudice for being both gay and Black.

From almost the beginning of their relationship, Locke would surpass his mentor in the breadth of his vision of diversity. As early as 1908, Locke gave a farsighted speech at Oxford’s Cosmopolitan Club praising, in his words, “a divided nationalism within one political nation, an ideal difference within a geographical unity, and a cosmopolitanism within a nation.” By 1911, he published several articles espousing the cross fertilization of a panoply of cultures—including Black and white—a perspective far broader than Kallen’s.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Locke prodded his friend to widen his vision of cultural pluralism and include African Americans and other non-European groups in his theory. Kallen’s focus had shifted after World War I to other concerns, among them fighting for wider civil liberties and awakening the public to the rise of fascism. But with the spread of a new war and racial atrocities across Europe and Asia in the early 1940s, Kallen at last heeded Locke’s advice, expanding his vision of pluralism and eventually publicly recognizing his colleague’s original role as the concept’s co-creator. Deeply influenced by Locke, who died in 1954, Kallen’s racial awakening continued to encompass an ever-wider universe of humanity until his own death in 1974.

The fearmongering, hate speech, and demands for 100 percent Americanism that Kallen, Locke, and others witnessed more than a century ago continue in fresh forms today. This new authoritarian era of closing borders and vilifying people of color has made Kallen and Locke’s pioneering work increasingly relevant. For, in order to truly realize our nation as a perpetually unfinished, open-ended project that offers hope to a divisive world, pluralists and the larger public must forcefully reject fearmongering against any and every minority group. By following this path, we might finally begin, in James Baldwin’s words, to “end the racial nightmare, achieve our country, and change the history of the world.”

Barack Obama’s vision, expressed in 2020, of America as “the only great power in history made up of people from every corner of the planet, comprising every race and faith and cultural practice,” echoes such enduring pluralist hopes, as does his faith that we will succeed in this experiment because “we come from everywhere, and we contain multitudes.”

Send A Letter To the Editors