A 1920s undergarment shop, an era in which “women sought to liberate themselves through attire.” Courtesy of National Photo Company Collection (Library of Congress).

In a recent Instagram conversation with fans, actress Gillian Anderson articulated what many women are thinking these days: “I’m not wearing a bra anymore … it’s just too f**king uncomfortable.”

The pandemic has changed the way women dress; we’re purchasing fewer shoes, dress pants, and makeup, and trading underwire bras for loose bralettes or sport bras, or even choosing to forgo them completely. Yet, as businesses around the country get ready to call their workers back to the office, this life of loungewear might be coming to an end. And as women contemplate their return to formal wear, the return of the bra might be one of the most dreaded aspects of post-pandemic normalcy.

This struggle is not new. Women have long connected clothing with ideas of freedom, and there is a long and strong relation between women’s demand for sartorial comfort and feminist ideas. Indeed, for many women, both in the past and today, discarding bras is not just an act of personal choice but an act of feminist rebellion.

The association of bras, and similar undergarments like corsets, with discomfort, oppression, and distress, goes back to the 19th century. Then, members of the nascent feminist movement sought simultaneously to free themselves from oppressive legal and social systems—and from tight corsets and trailing skirts. “Something of the nature of the American costume … must take the place of our present style of dress, before the higher life—moral, intellectual, political, social or domestic—can ever begin for women,” feminist Elizabeth Stuart Phelps argued in 1873. Phelps called women to burn up their corsets, arguing that by freeing themselves from discomfort they could truly experience emancipation.

And in the second half of the 20th century, burning bras (or corsets)—whether as a real act or as a metaphor—would become one of the most popular images representing a new generation of feminists. Arguing that “the personal is political,” these feminists sought equality in all realms of life, from the home to the workplace, demanding control over their uteruses as well as their clothing choices. No bras were burned in the famous “No More Miss America Protest” of 1968—though some were thrown into a trash can along with lipstick and high heels. But the media was quick to associate bra burning with the radical feminists who protested oppressive beauty standards.

Yet before women’s fraught relationship with their undergarments became a symbol of radical feminists, women sought to liberate themselves through attire. There was, in fact, a similar push a century ago—in the shadow of another global pandemic and the realignment of world order after World War I. Emboldened by the right to vote and the social changes it brought, young women in the U.S. and elsewhere began to reevaluate their position in society as well as their appearance. Funny enough, in doing so they popularized the now-reviled bra.

Pre-World War I, in response to women’s growing involvement in sports and leisure, the fashion industry began marketing lighter, less restrictive corsets and more flexible girdles in an attempt to maintain their profits. Into this atmosphere, a relatively new undergarment emerged as a corset substitute: the brassiere. Although its origins are somewhat unknown, in the U.S., socialite Caresse Crosby patented her brassiere design in 1913.

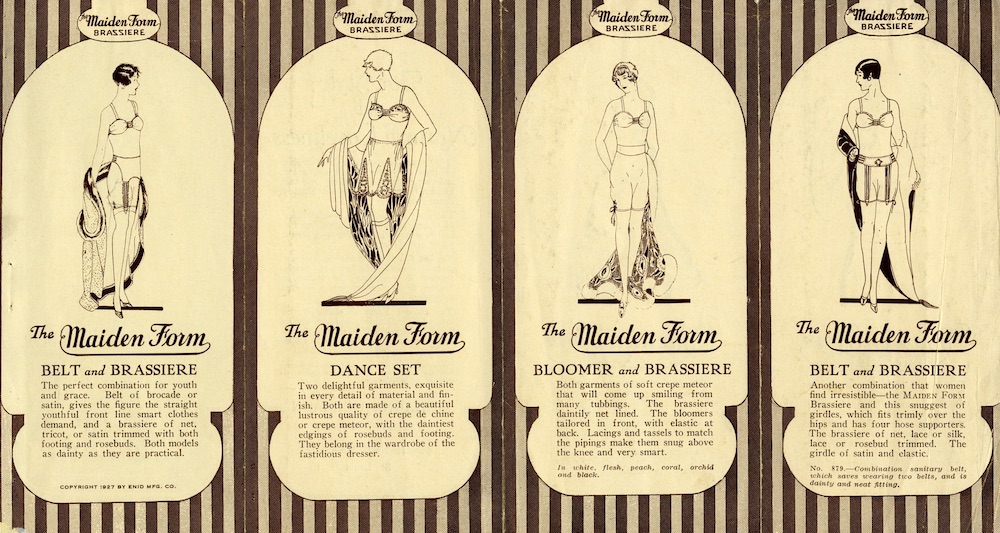

A Maidenform bra advertisement. Courtesy of Smithsonian Museum of American History.

Women’s growing mobilization into the workforce and social reform during the 1910s only increased the demand for sartorial change. The U.S. entry to the war in 1917 and the influenza pandemic in 1918 also affected changes in fashion. By the 1920s, young women shortened their skirts and hair and discarded their corsets, often in favor of a bra, insisting on wearing comfortable clothing that suited their active lifestyles and to celebrate their sexuality without being reprimanded for it.

“’Let Go’ is the law of the new corset and the corsetless figure,” exclaimed Eleanor Chalmers, fashion editor of the women’s magazine Delineator, in 1922. These new fashions became identified with the image of the modern flapper. But they also became both a visual and symbolic statement of a new feminine presence in the public sphere. By forgoing their corsets, women were also forgoing the ideas that were attached to them: confinement, passivity, and oppression. The corsetless figure became the epitome of women’s social and political freedom and mobility, forging a new beauty ideal that was younger and slenderer.

Some of the first widely marketed bras of the 1920s had a flattening effect that fitted the straight, rectangular silhouette of the flapper ideal. But unlike boned corsets, these bras gave only minimal support, functioning more as an extra layer beneath clothes than a means to mold a woman’s torso.

Taken together, the new flapper dresses and the bras beneath them became a means for women to assert their power as consumers and their rights. “They demanded independence, and they got it … when they went shopping they asked for what they wanted, instead of what they saw,” explained fashion consultant Margery Wells in 1928 as she looked back at the shift in Women’s Wear Daily. Instead of being followers of fashion, women began to actively voice their preference.

The ideal silhouette evolved alongside undergarments—and social reform. Women’s Wear Daily.

By the end of the 1920s, with the coming of the Great Depression, the youthful, leisurely flapper ideal seemed out of touch. Instead, a more mature and curvier silhouette gained popularity. Bras became undergarments responsible for enhancing and uplifting the breasts and creating a more structured shape, similar to the function we chafe against today. Yet the emphasis on comfort, whether imagined or real, continued to be part of the selling message for women.

Over the next four decades, the bra progressed slowly from an item associated with women’s liberation and self-dependency to another confining and restrictive garment associated with women’s oppression. Indeed, it was the meanings that women gave their bras in the postwar, post-pandemic 1920s, more than the design itself, that offered women a sense of liberation. And it was the meanings, not the design, that feminists in the 1970s found so abhorrent.

In the 1920s, fashion was where women turned to convey their new reality. And today, amidst a pandemic, bras once again become a symbol of the limitations on women’s experience in the labor force. As women reevaluate their social position, the sound of rebellion is getting louder. Even if COVID will not bring a wave of bra abandonment, women today are already making fashion choices that will impact our future. And if history is a lesson, we are in for an interesting ride.

Send A Letter To the Editors