The Photo Album That Succeeded Where Pancho Villa Failed

The Revolutionary May Have Tried to Find My Grandfather by Raiding a New Mexico Village—But a Friend’s Camera Truly Captured Our Family Patriarch

For a long time—at first sporadically but lately in hot pursuit—I’ve been looking for Sam. Sam is Sam Ravel, my paternal grandfather. I scour the indexes of history books for his name, search archives across the country for references to him, and probe the recesses of my memory for details of his life from family lore. But the artifact that has opened an entirely new and exciting aperture into my grandfather’s life was one I’d first seen decades ago.

Sam is my family’s patriarch, the immigrant who made our branch of the Ravel family American. But he’s notable for a more provocative reason: It’s long been rumored that when Pancho Villa raided the village of Columbus, New Mexico in 1916, he was looking to kill Sam.

Who was Sam? And how did this Jewish immigrant from Lithuania land in a dusty border town and get tangled up with Villa, one of Mexico’s most notorious figures?

Sam Ravel arrived at the port of Galveston, Texas in 1905—one of millions of Jews escaping economic hardship and antisemitic persecution in Eastern Europe. He settled with relatives in El Paso before moving to Columbus in November 1910.

Sam’s arrival in Columbus roughly corresponded with the start of the Mexican Revolution, a decade-long, bloody struggle to end an era of dictatorship in Mexico and establish a constitutional republic. As the leader of the División del Norte, Villa was one of the Revolution’s most prominent, and, to the U.S., proximate leaders.

Sam operated two retail businesses in this town just north of the border: the Commercial Hotel and the Columbus Mercantile Company, which he renamed Sam Ravel & Brothers once his younger siblings, Louis and Arthur, joined him in America. The store sold ammunition, appliances, cleaning supplies, clothing, food, fuel, guns, hides—you name it.

Like their merchandise, their customer base was diverse: Americans, including the local Army troops from Camp Furlong, Mexican civilians, and Mexican revolutionaries jockeying for power. With war south of the border came a military buildup that spurred population growth, which generally made for good business. But on March 9, 1916, the Revolution spilled north onto U.S. soil. Before dawn, Villa’s army galloped into town, guns blasting, shouting “¡Viva Villa!”

The assault that followed was audacious, and notorious—the only time in the 20th century that the continental United States was invaded by a major foreign army. The Villistas looted Columbus and set fire to several buildings, including the Ravel-owned Commercial Hotel, which burned to the ground. A gunfight erupted between the Villistas and the U.S. Army, and the Villistas retreated by daybreak. The casualties were substantial: Nine local military officers, 10 civilians, and approximately 78 members of Villa’s army lay dead in the streets.

Villa was likely motivated to attack by a constellation of reasons, among them anger that the U.S. had shifted their support from him to his rival, Venustiano Carranza. But more than 100 years later, in both popular narratives and history books, a rumor persists that Villa had come to Columbus because he was enraged at Sam over an arms deal gone wrong. Accounts relay that a contingent of Villistas scoured for Sam, even commandeering his teenage brother Arthur in the search. The revolutionaries never found Sam, because he was in El Paso for a medical appointment.

Was revenge against my grandfather really a motivation for the attack? This bizarre notion has intrigued me ever since I was a child.

To learn more, in March 2016—100 years after the raid—I joined family members in Columbus for the annual memorial commemorating the event. We listened to speakers, took a walking tour of the town, and had lunch across the border in Palomas, Mexico.

I returned home to California with even more questions about Sam, and began my search in earnest. I dove into research, and returned to Columbus to film 2020’s raid commemoration for a documentary I hoped to make. Over a few years, the fuzzy facts of my grandfather’s life came into greater focus.

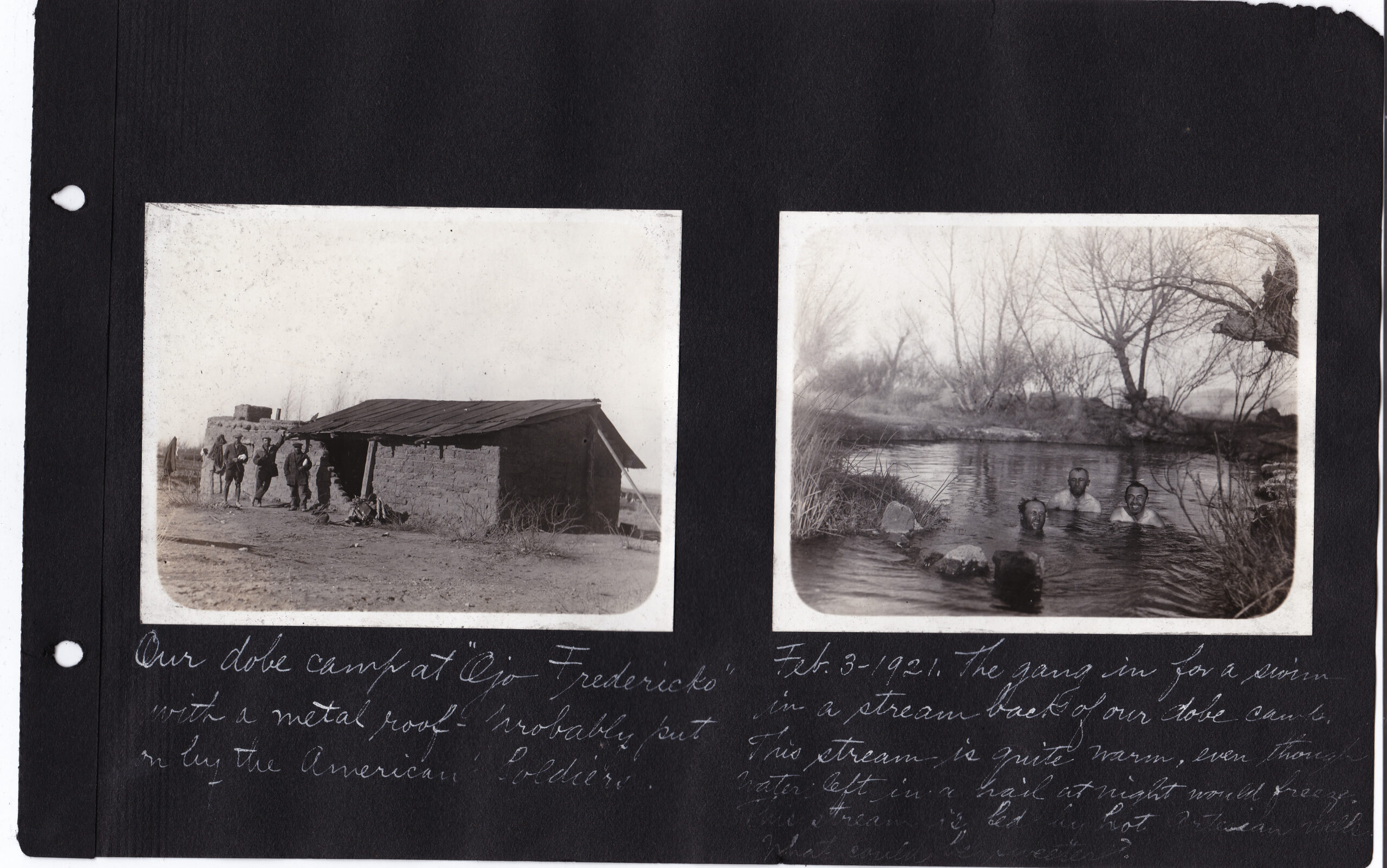

Ultimately, one of the most fruitful sources of insight into my grandfather was neither scholarly archives nor family lore, but a gift Sam received long ago. It was a glorious, 101-year-old black-page photo album documenting a hunting trip he took with friends in Chihuahua, Mexico in 1921. This album brought me closer to Sam, revealing some of his authentic nature and interests. Over time, I’ve come to feel as if I know my ghostly grandfather in large part due to conserving, examining, and revisiting its photographs and captions.

I first saw the book years ago, during a visit to an aunt in my hometown, San Jose, California. As we reminisced about the Ravels, my aunt pulled the album from a shelf in the family room. The cover was embossed in gold with the words “Snap Shots.” It had likely sat unopened for some time, but it was falling apart. Pages were crumbling. Captions handwritten in white ink were fading.

At the time I worked at Getty Publications, so with my aunt’s permission, I brought the album to work and showed it to a conservator at the Getty Conservation Institute. My colleague advised me to carefully remove the brads that bound the book and were putting pressure on the page edges, to slide each leaf into a clear sleeve, and to store the album in an archival box in a dark closet. Once the album was stabilized, I could examine it more carefully, and frequently, without fear of it disintegrating. I pored over the images and transcribed the annotations.

Created and given to my grandfather by one of his travel mates, the album documents their two-week trip into Mexico in January and February of 1921, mere months after the Revolution ended and just five years after the deadly raid. Villa was still at large.

The book begins with streetscapes of nearby Texas cities, perhaps taken from the window of a westbound train: Main Street in Van Horn, Fort Hancock, and then tiny Yselta, which the unknown author ironically captions “another large town.” Next there is a glimpse of downtown El Paso. Model Ts are parked in front of the stately Hotel Paso del Norte, where people had flocked to the rooftop terrace to watch firefights across the border during the Mexican Revolution.

Sam comes into the picture, literally, on page five. Before studying the album, I had seen only two photographs of him, both studio portraits. In the earlier one—likely taken in Europe before Sam emigrated to America—he is seated next to his two younger brothers. They are somber, wearing dark suits, possibly mourning their mother’s death.

The only other photograph I had seen of Sam is similarly posed, self-conscious and formal. Set in a filigree gold frame that my father kept on his dresser, it now hangs in my house. In this one my grandfather is older, fatter, and with less hair. Again he dons a three-piece suit, but this time it’s accented with a spiffy botanical print tie, and he smiles slightly.

In contrast, the album presents pages of unguarded moments. And while posed—Sam and his friends certainly knew they were being photographed—these images are the antithesis of formal studio portrait photography: casual, spontaneous, even playful.

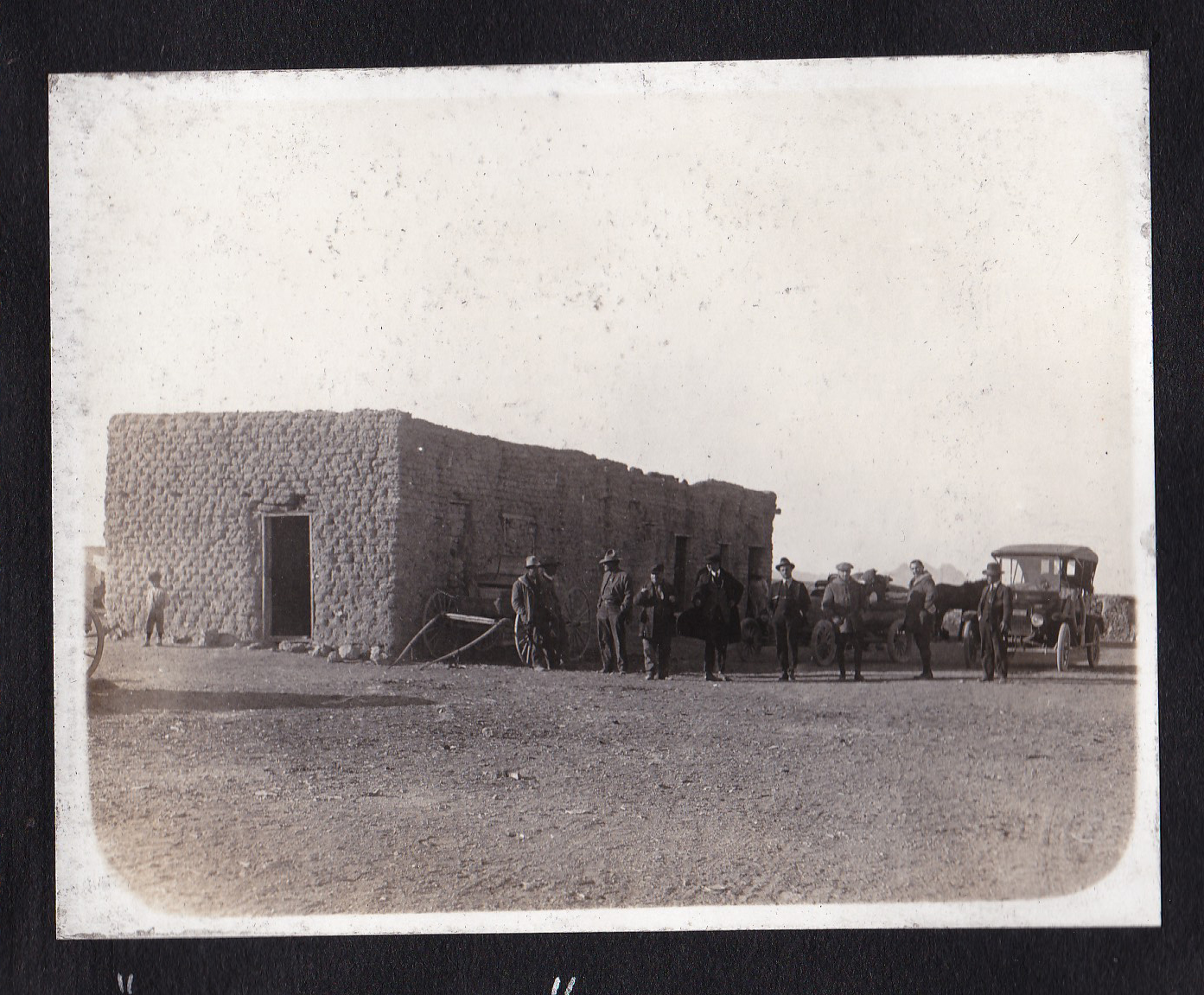

In one Sam is lined up with a group of men in front of an adobe in Palomas, looking like a still from The Magnificent Seven. It is January 25, 1921, the first night of their journey. In the next photo Sam and two buddies stand before the hut where they bedded down for the night. A cigarette dangles from his right hand; a chicken pecks in the foreground.

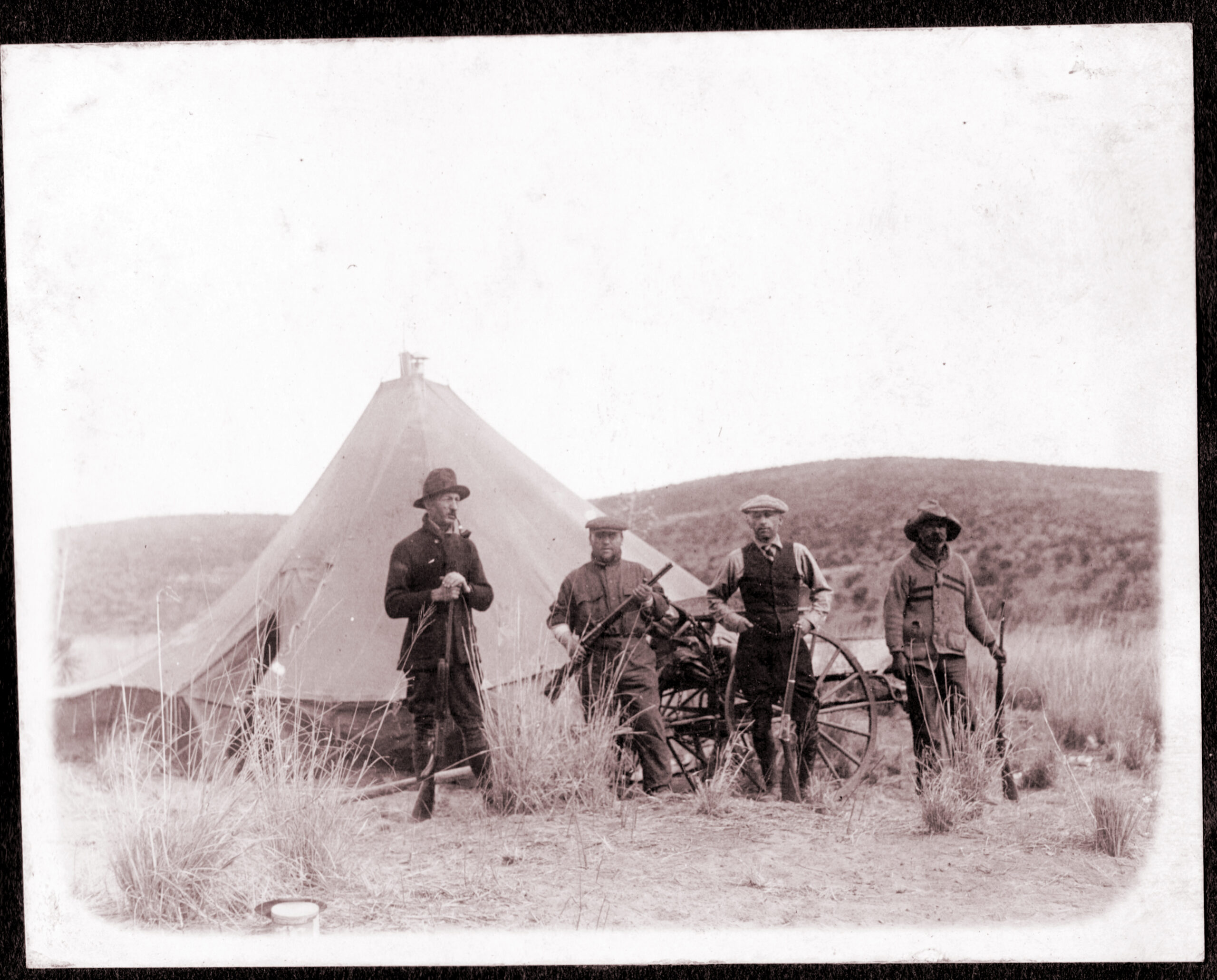

Photo by photo I am introduced to their hunting guide, their horses, even their first campsite, where my grandfather postures with a rifle at the ready. He seems unconcerned that Villa is on the loose.

Relatives reported that Sam was gregarious and audacious, and here is evidence: a photo of Sam and his companions stripped down and bathing in a hot spring, their faces plastered with toothy grins. In another shot he gamely cradles a live fox.

Was he hearty, as I imagined an immigrant forging a better life for himself and his siblings, would be? I turned a page and there was my answer, inscribed by the author beneath a scraggly headshot: “Sam Ravel alias cold blooded Sam. He slept comfortably in his underwear while we froze to death with our clothes on and shoes on … and some snorer.”

I eventually made my film about Sam, UnRaveling, and these photographs are the connective tissue—providing levity, context, nuance, and authenticity. The album was meant as a gift to my grandfather whom I never met, but it was also an enormous gift to me. I have sat with this heavy album in my lap many times, studying its now-delicate pages, as I imagine Sam also did. I linger over the inscription:

With my best wishes to Sam Ravel

Remembrances of our Hunting Trip in Mexico

Jan. and Feb. 1921

Send A Letter To the Editors