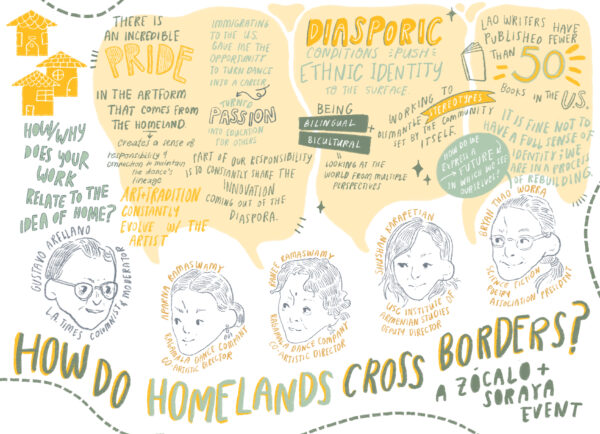

From left to right: Gustavo Arellano, Aparna Ramaswamy, Ranee Ramaswamy, Shushan Karapetian, and Bryan Thao Worra. Photograph taken by Luis Luque | Luque Photography

Home can be physical or imagined—a point of departure and return but also a memory or feeling. When migrants and immigrants move across borders, they bring along the places they leave behind through language, art forms, religion, food, and culture. How does that movement shape them, and the places they depart and arrive? And how do they navigate the burdens of supposedly representing an entire culture, nation, ethnicity?

These were the guiding questions posed to a panel of cultural practitioners at last night’s Zócalo/Soraya event, “How Do Homelands Cross Borders?” Presented in conjunction with an upcoming performance of Ragamala Dance Company’s Fires of Varanasi, the event was streamed in front of a live audience in The Soraya’s vastly windowed lobby, overlooking the CSUN campus. The panel encouraged the audience to share their own stories about who they are and where they are from and to demonstrate that cultures are not static but, rather, are characterized—like migrants—by movement.

The evening’s moderator, Los Angeles Times columnist Gustavo Arellano, began with an exercise of scale: asking the panelists to think in both macro and micro terms about the first side of their hyphenated identities. “I’ll start. I’m Mexican-American,” he said, then zoomed in, explaining that his family is from the state of Zacatecas, the Municipio de Jerez, and the small village of El Cargadero. Arellano also explained that there are over a thousand people with roots in El Cargadero in the Orange County city of Anaheim, where he grew up, highlighting how communities make homes across borders. All of the panelists took their time answering—making it clear that their hyphenated identities complicated where exactly “home” was.

The panelists all use their cultural homelands and ethnic identity in their professional work. Arellano asked, “Why?”

Dancer and choreographer Aparna Ramaswamy, who co-directs Ragamala Dance Company alongside her mother and fellow dancer and choreographer, Ranee Ramaswamy, described the great influence Ranee had in inspiring her to mine the thousand-year-old tradition of Bharatanatyam dance. Ranee, in turn, explained that growing up in India, the only plans for her were to “be a housewife.” After moving to Minnesota in 1978, she discovered a demand for classical dance from the burgeoning Indian community, who wanted their children to learn “home” traditions.

Shushan Karapetian, deputy director of USC’s Institute of Armenian Studies, describes herself as a “professional Armenian.” Somewhat jokingly, she said that her doctorate in Armenian studies was part rebellion against her immigrant parents’ wishes for her to become a medical doctor. But the short answer, for Karapetian, had everyone nodding in agreement: “We all do what we do to understand ourselves better.”

Arellano reinterpreted the question for Science Fiction Poetry Association president and poet Bryan Thao Worra: As a writer, how important is being Lao?

Worra was born in 1973 during the CIA’s secret war in Laos, and adopted by an American pilot. When he began writing poetry in earnest, he realized he was straddling two boats down a tough river—one his American and the other his Lao identity. In literature, where he saw depictions of Asians as targets and prostitutes, Worra found an opportunity to create imagined worlds in which he could see himself and his community in absence of meaningful representations of Lao people. “In science fiction,” he said, “we had this challenge of how do we express a future in which we see ourselves?”

Worra’s struggle speaks to the burden of representation that all of the speakers feel at one time or another. Karapetian said that she saw it as her mission to correct stereotypes non-Armenians have of Armenians and those stereotypes Armenians hold about their own community. She described two major narratives in the Armenian community: one of the ancient past full of glory and the other of the post-genocide victim. Through her work around the Armenian language, Karapetian challenges these notions of the homeland and recreates Armenian identity as plural. She also does this work in raising her children, upon whom she “imposed” Armenian names and language—who, born and raised in Los Angeles, see themselves as Armenian simply because they speak the language and eat the food.

Aparna Ramaswamy echoed the need to recreate traditions and pull them into the present, citing the ways she and her mother make the long and storied history of Indian dance contemporary. “Our responsibility,” she said, “is constantly sharing the innovation that exists in the diaspora, at home, and within each of us.”

As audience questions streamed in, Arellano read out the brief, personal diaspora histories people had shared in the live chat: people raised in Guam; people from Jalisco, Mexico; people unsure of what country their family came from due to shifting borders and unreliable narrators.

When posed with a question about losing traditions to Americanization, Worra responded in verse, reading from a poem he wrote about eating dinner with his biological family—who immigrated to Modesto, California:

It’s Taco Wednesday tonight,

With nachos and hot dogs,

Spaghetti and papaya salad,

Some brisket and jaew.

I eat politely, as home here as anywhere, with a smile.

The discussion concluded as it began, with the eponymous question of the event. “How do homelands cross borders?” Gustavo asked. Each panelist answered in part: family, food, language, encounters.

But they all agreed, in one way or another, that homelands and cultures cross borders with people—real life, skin-to-soul humans.

Send A Letter To the Editors