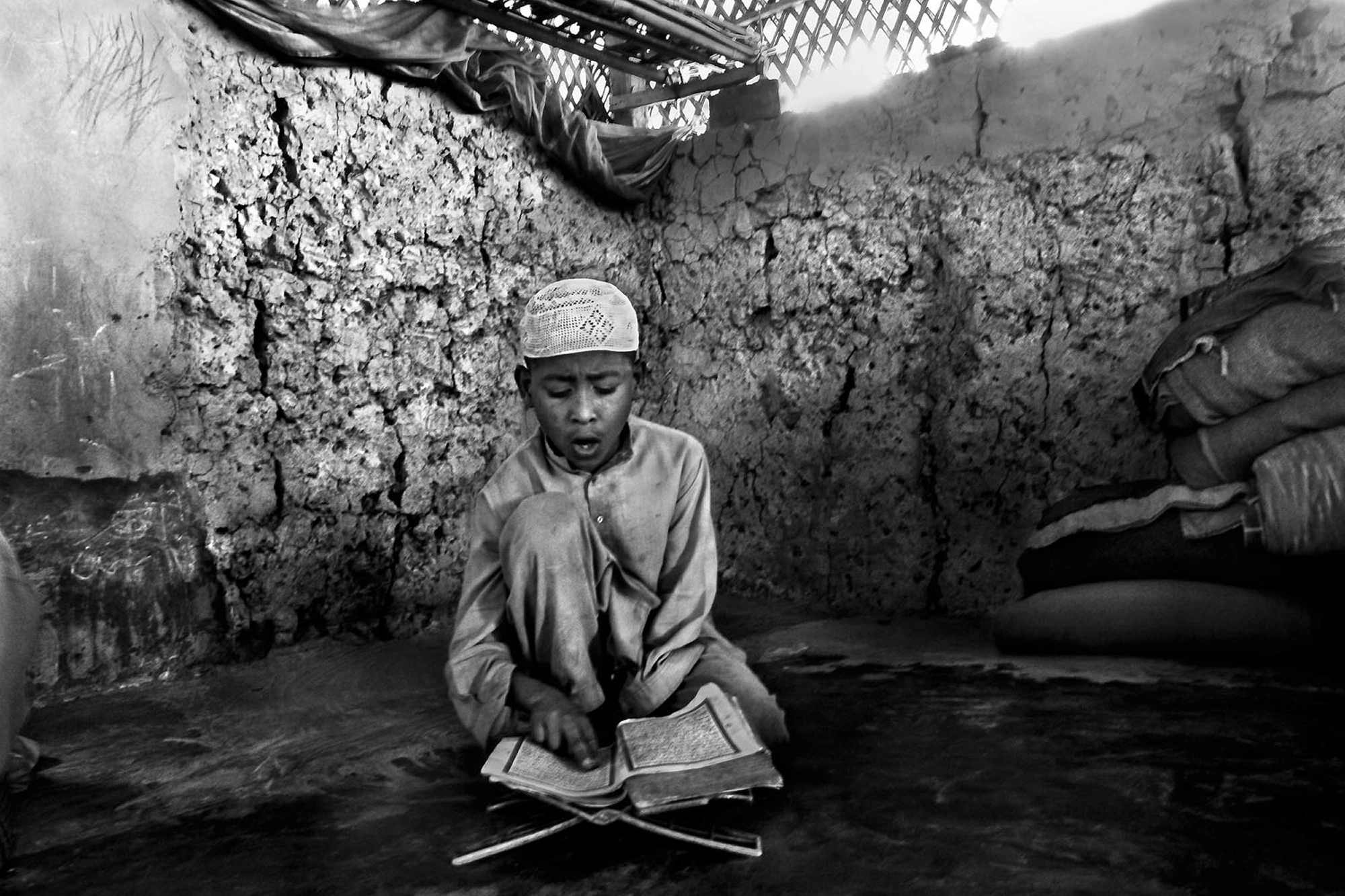

Nayapara refugee camp is one of two government-run refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, a coastal district in Bangladesh. The camp is inhabited by Rohingya people who fled from ethnic and religious persecution in neighboring Myanmar. Courtesy of Saiful Huq Omi/Counter Foto.

In 2015, the image of a Syrian child, drowned and washed ashore near the Turkish town of Bodram, went viral. This singular, visceral image of the hapless refugee victim spoke to what the political philosopher Hannah Arendt—herself a refugee who survived the Holocaust—called the “politics of emotions”: our unstable, image-driven will to humanitarianism. But even as images like this spurred donations and the opening of borders, countless simultaneous narratives portrayed Syrian men seeking refuge as rapists and violent aggressors. Both stories showed the refugee as either victim or perpetrator, closing off any deeper examination of who these people were, their motivations for moving across borders, and what their lives were like after leaving home.

Resettlement is much more complicated than either of these narratives—as are refugees themselves, who possess a wide variety of social and political identities, even in closed humanitarian spaces like refugee camps. Refugees carry the heavy memories of distinct and violent histories as they move across borders and face the multiple, layered histories of the places they resettle. One way to begin to grapple with mass displacement caused by human transgressions is to try and understand their condition.

I work in refugee camp settlements in southeastern Bangladesh, which house close to one million Rohingya, an ethnic group of predominantly Muslim people from neighboring Myanmar. Despite the collective vulnerability and the apparent uniformity of life inside the camps, political and social class manifests itself in subtle, yet observable ways.

The Indian subcontinent as a whole is no stranger to the chaos of mass displacement, with the partition of India and Pakistan (of which Bangladesh was then part) in 1947 which spawned what is considered to be one of the largest episodes of forced migration, with around 15 million displaced. And Bangladesh’s war for independence from Pakistan in 1971 produced around ten million refugees, some of which remained stateless until 2000. Bangladesh’s present-day will to humanitarianism is ensconced in its collective memories of the upheaval of displacement in the scale of millions and the memory of the terror of those times.

The latest influx of the Rohingya into Bangladesh took place in 2017 as a result of a systematic ethno-nationalist campaign of violence by the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military. The Biden administration recently made a formal declaration that the Tatmadaw’s mass killings, rape, arson, and the razing of villages constituted genocide against the Rohingya minority. Stripped bare of any citizenship rights and forced to flee, the Rohingya entered the borders of Bangladesh.

Despite the goodwill engendered by Bangladesh’s open border policy with regard to the Rohingya, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has told the UN that the Rohingya refugees must return to Myanmar. Refugees face the hardships of resettlement and statelessness inside the settlements scattered across the country’s southern border. During the summer of 2017 I visited Balukhali (which later became part of the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp or “mega camp”- the world’s largest by population) amidst the chaos of thousands of new arrivals each day. At a glance, the camp appears to be a great equalizer: Everyone lives in makeshift bamboo and tarpaulin shelters, and everyone is vulnerable to monsoon rains and landslides thanks to the hilly terrain.

But while females constitute over half of Bangladesh’s Rohingya population, and over half are also children under the age of 18, the majority of the settlements’ appointed leaders are men who either held property or owned businesses back in Myanmar. These leaders oversee smaller administrative units within the settlements with the task of reporting on problems with relief disbursal and any conflicts within their jurisdiction. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other agencies operating inside the camps are seeking ways to make these governance structures more inclusive and transparent. But the adoption of gender quotas and elections varies across the different settlements.

There is also financial stratification within the camps. Rohingya-owned businesses inside the settlements include pharmacies, tailoring shops, restaurants, and shops that sell packaged food and durable items like batteries and electronics. Business owners rely on inventory loans from nearby Bengali enterprises. Often these Rohingya business owners were involved in commerce back in Myanmar, and many have formed relationships with Bengali business owners also operating inside the camps. At the other end are the Rohingya who take up ad hoc day labor jobs inside the settlements, primarily in construction. And some refugees work for the NGOs and UN agencies and receive more stable incomes.

Camp settlements like Kutupalong, which I last visited in the summer of 2021, reproduce the conflicts of the local communities back in Myanmar. Complex, organized networks involved in human trafficking and drug smuggling coexist alongside the proliferation of U.N.-based agencies and other NGOs, both international and local, that operate inside the settlements. The government of Bangladesh has made progress in increasing prosecutions and convictions of trafficking-related crimes and kidnappings. But trafficking to India, Thailand, and Malaysia remains a major problem.

Politics divide the Rohingya in Bangladesh as well. Two major groups have clashed over repatriation. The Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) represents a militant insurgency group known to operate inside Myanmar. According to my interviews with local Rohingya leaders, they hold covert military trainings in forest areas around Kutupalong. Bangladeshi law enforcement agencies also reportedly periodically seize ARSA arms and ammunition from inside the settlements. The ARSA seeks the self-determination of the Rohingya but have not readily supported recent repatriation initiatives.

On the other hand, the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights (ARSPH) has made clear demands for repatriation, including via a “Go home” campaign that includes a Twitter presence. The leader of this movement was recently murdered, with some speculation that the ARSA may have been involved. These sharp tensions point to the lack of a unified political voice amongst the Rohingya, and that the path forward to political sovereignty and rights is by no means clear.

In fact, the very legal identity of the Rohingya in Bangladesh is also split: between those who arrived in the early 1990s (when a previous genocidal campaign was launched against them in Myanmar) and have formal refugee status, and the post-2017 arrivals. This more recent group, declared as forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals, have not been accorded refugee status nor are they even recognized as stateless. As a result, they are ineligible to apply for asylum- and in fact do not have claims to rights under any rights-affirming state or body. These differences in legal status accorded by the Bangladesh government signify how the instrument of memory and the shared remembrance of the country’s own violent past have cleaved to both include and exclude the same group of people with the same history of persecution.

Arendt pointed out that the anachronistic rightlessness of the refugee, which came from a lack of membership within any political community, was tantamount to an expulsion from humanity. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt wrote, “The calamity of the rightless is not that they are deprived of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness … Their plight is not that they are not equal before the law, but that no law exists for them; not that they are oppressed but that nobody wants even to oppress them.”

The case of the Rohingya, nevertheless, demonstrates that there are degrees of expulsion and inhumanity in refugee societies. Refugees don’t all play either the victim or the perpetrator. Rather, they live complex, hierarchical social and political lives. We need to listen to their stories and understand their conditions in order to confront the histories of mass displacement, and maybe even address them.

Send A Letter To the Editors