The question of how a society should remember its transgressions carries with it substantial weight. How does one begin such work? Is the act of remembering, in and of itself, enough? And more importantly, can the intensive work of confronting one’s history ensure the desired outcome—that we will not be doomed to repeat the horrors of the past?

While some societies have grappled with their pasts with varying degrees of success, there is no ready-to-use template for Americans to adapt. In broad terms, when other nations have addressed their past crimes, the events were more recent, rather than centuries old; the work is often done under the auspices of a transitional government’s truth commission; or the nation is under international pressure, politically and economically, to address past wrongs. Where does that leave the U.S., which today has yet to address its centuries-old transgressions, which include the genocide of Native Americans and the enslavement of African Americans?

In early 2022, as we launched our work on the editorial and public programs series, “How Should Societies Remember Their Sins?,” we understood these difficult questions to be part of an emerging field of study and practice that has more questions than answers. As an acknowledgment that this inquiry requires a collective and cross-disciplinary approach, we convened an advisory group of eight scholars and practitioners from different fields, each of whom confronts fraught histories in their work. The goal for the two conversations we held with the group was to learn from the best practices and historical precedents of different disciplines, and to see if a new, shared knowledge could emerge.

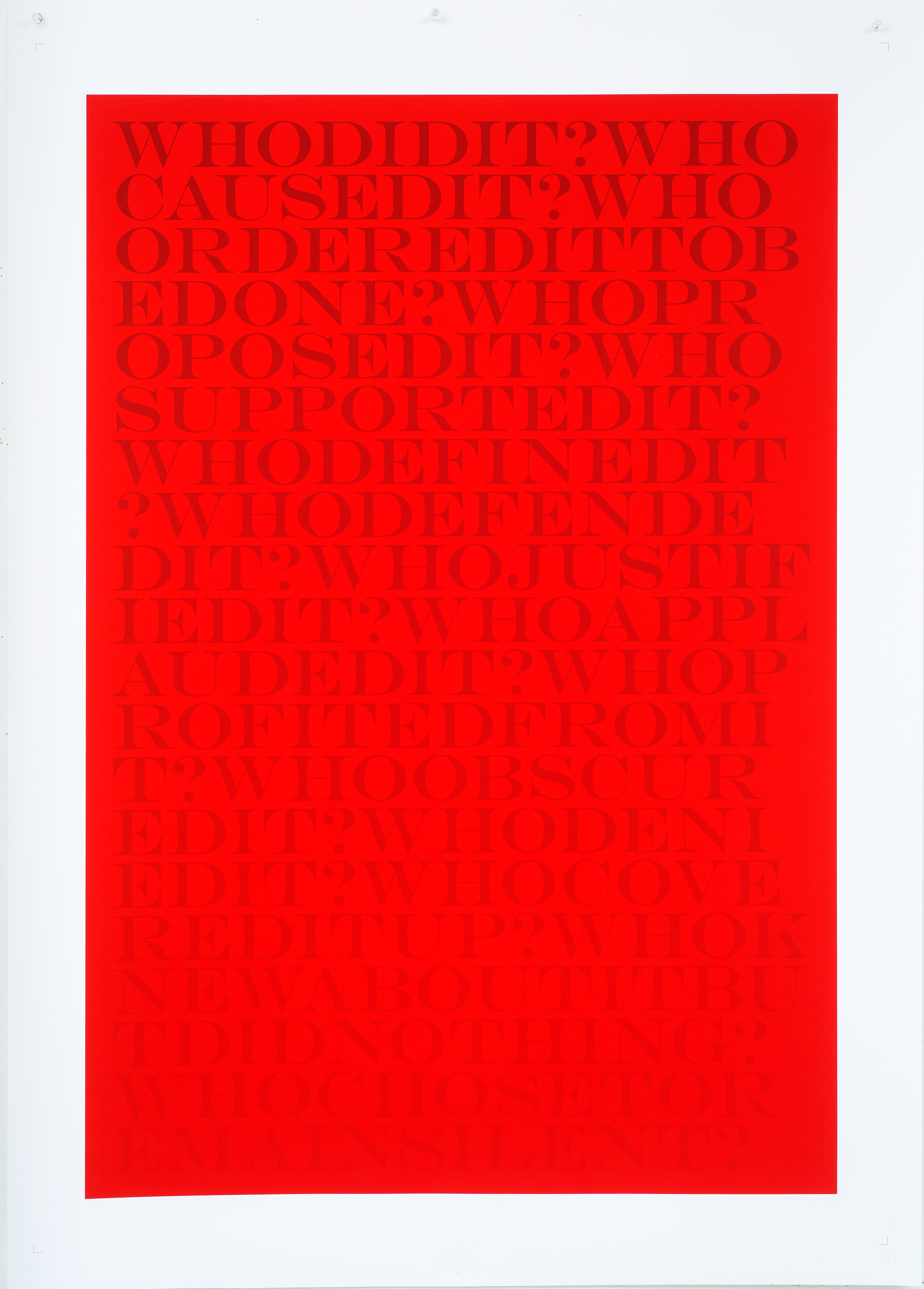

“Who did it? Who caused it? Who ordered it to be done? Who proposed it? Who supported it? Who defined it? Who defended it? Who justified it? Who applauded it? Who profited from it? Who obscured it? Who denied it? Who covered it up? Who knew about it but did nothing? Who chose to remain silent?”—Dorit Cypis, “Who Did It (alert)”, 2013-2015. Series of 5 prints – green – blue – yellow – orange – red. Archival pigment, Hahnemuhle rag paper, 40 x 30 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

The discussions yielded several crucial insights, outlined below:

Testimony about past wrongs alone doesn’t soothe victims or influence perpetrators—people need collective processes that transform their relationship with painful histories. The historian in our group once gave a lecture in the South, informing locals their town had been named after a Klansman. Following the murder of George Floyd, the attorney in our group worked with a City of Los Angeles initiative in which residents offered first-hand accounts of their experiences with police abuse, to be summarized for the Los Angeles Police Department with recommendations for policy changes. Neither historian nor attorney felt that their interventions conducted sufficient follow-through with the impacted groups. Most survivors don’t find talking about their stories useful, the psychologist in our group added—but framing testimony in a useful context such as a collaborative, creative effort can have a transformative impact, pulling people from the isolation of trauma and restoring their relationship to community. He suggested that the attorney’s efforts carried the promise of transformation. In response to the historian’s concerns about stirring up anguish in the town named for a Klan member, the rabbi in our group argued that change requires a three-part process of agitation, innovation, and orchestration—and no single individual can be expected to take on the full arc.

There’s a fraught relationship between apology, amnesty, forgiveness, and repair. The architect in our group noted that in Argentina, many survivors and descendants of survivors oppose reparations, seeing a tension between justice and symbolic monetary compensation that might close the door to restorative conversations. In other countries, offers of amnesty, provided in part to surface difficult truths, have been fraught with controversy and implications of impunity. Sometimes apologies flow from governing bodies or institutions unrelated to the source of the harm. In the case of the U.S., the group asked how we could deal with harm from perpetrators long gone, where justice is difficult to imagine. Can we find a collective way to think of justice outside of the legal system, particularly when offenses are centuries old?

Moving on from past traumas requires a multitude of voices and approaches, including our senses of humor. As a member of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, the journalist in our group noted that a certain irreverent humor is central to Indigenous culture and its resilience in the face of injustice. Scholars who focus on heavy topics need levity and humor, the panel agreed, and suggested that Zócalo’s series should approach its work through a variety of tones.

Societies need better tools to engage with this emotionally difficult work, including new vocabularies that reflect an evolving political landscape. We are responsible for people’s pain from the process of remembering, and we need to develop strategies to calm and reground ourselves, the psychologist in our group noted. The political scientist in our group cautioned that confronting fraught histories can be a decades-long process, and the architect advised that the public should be prepared to engage in some discomfort while working toward justice. Five members of the group critiqued the series name, arguing that the word “sins” is problematic: People commit sins, not societies. The use of the word also implies that the sin might be forgiven, thereby relieving citizens of the responsibility of grappling with moral transgressions. Remembering, too, they argued, doesn’t go far enough. But problems with the series title might present opportunity; the right language could emerge during the course of the work.

Some of the members of our group grappled with the gravity of our question, which they agreed should ideally be engaged and led by a governmental body, rather than a nonprofit. A few members suggested that we should create an index of past global efforts as a way to signal that this work, though fraught with challenges, is possible. We offer this summary of our process in the spirit of transparency, and to propose that collective engagement can make this work more tenable. Over the two-year span of this series, grounded by the key insights from our advisory group, Zócalo will share 24 essays and four public programs that explore the process of remembering and recovering—from conflict, to collective memory, to societal attempts at repair, and imagining new paths forward.

—

Advisory Group Members

Gloria Y.A. Ayee, political scientist; lecturer and senior research fellow, Harvard University

Justus Baird, rabbi; senior vice president, Shalom Hartman Institute of North America

Courtney Morgan-Greene, immigration attorney; commissioner, Human Relations Commission, Civil + Human Rights and Equity Department, City of Los Angeles

Chon A. Noriega, distinguished professor of film, television, and digital media, UCLA; former director of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Valentina Rozas-Krause, architect and architectural historian; assistant professor at Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez, Chile

Jack Saul, psychologist and artist, founding director of the International Trauma Studies Program

William Sturkey historian of the American South; associate professor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Patty Talahongva, journalist; senior correspondent, ICT

Send A Letter To the Editors