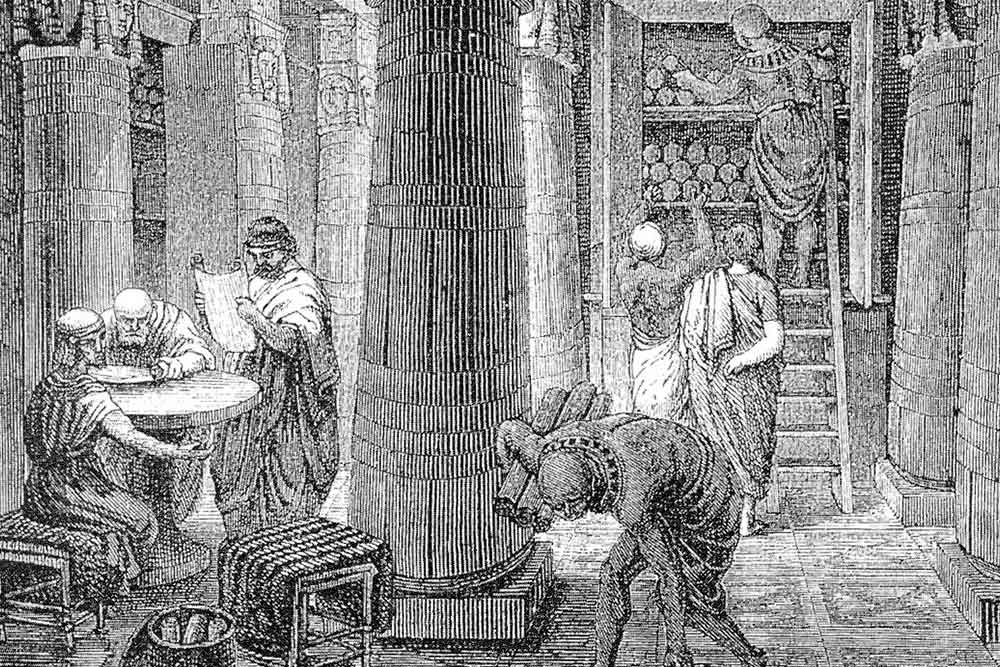

With the credits rolling on the golden age of streaming, we can draw perspective from the ancient Library of Alexandria’s demise, writes Culture Class columnist Jackie Mansky. Artist rendering courtesy of Public Domain

You log into a streaming service and the show you want to watch is gone.

Best-case scenario: it’s migrated to another major platform, and you already have an account set up there.

Less ideal, it has been folded into a smaller-tier streamer, the kind that offers its content for free, but with so many ads that the show is nearly unwatchable.

Then there’s the bleakest option. The show you’re looking for is gone. You can’t watch it. You can’t buy it (except maybe on used DVD or VHS, if you have a player). For all intents and purposes, it no longer exists.

“The creative community is in a state of dumbfoundedness,” entertainment journalist Matt Belloni recently told Marketplace. “I think they’re saying, ‘Wait a second, my show can just disappear?’”

Streaming video was supposed to be a story of abundance. Watch what you want, when you want. But the salad days are over. Today, there are more than 200 streaming services, and heightened competition alongside slow growth has led to price hikes and cost-cutting measures, including dropping shows to avoid paying residuals to actors and creators. The comedy Arrested Development, which Netflix is set to remove this month, is the latest to meet this fate. Due to its popularity, another streaming service will likely scoop the show up in its entirety (for now, you can still view the first three seasons on Hulu). But the future of dozens of less visible works of television and film remains unclear.

There’s a lesson here from the fall of the ancient Library of Alexandria.

The fabled library, believed to have been founded around 300 B.C.E. during the reign of Ptolemy I, is said to have contained the largest collection of manuscripts in the ancient world. The library sought to “collect the books in existence in every quarter,” calling on “every king and governor on earth to send ungrudgingly the books (that were within his realm or government),” including “the works of poets and prose writers, orators and sophists, physicians, professors of medicine, historians and so on,” according to one contemporaneous text. The library had reportedly acquired 54,800 scrolls at the time, and the account noted that this was just the start: “There is still a great mass of writings in the world, among the Ethiopians and Indians, the Persians and Elamites and Babylonians, the Assyrians and Chaldaeans among the Romans also and the Phoenicians, the Syrians and the [Romans] in Hellas.”

The library continued to grow in earnest, so much so that another branch was eventually built at the Serapeum, the sanctuary of the god Serapis, to house the overflow.

Then it all collapsed.

What can we learn from its destruction, some 2,000 years ago?

Myth-making often shrouds the answer. Take the famous opening episode of Cosmos, which sees Carl Sagan standing in front of what is left of the Serapeum. “Of that legendary library, all that survives is this dank and forgotten cellar,” he says, painting a bleak picture of the “pathetic, scattered fragments” of knowledge inside the building that survived the collapse. The task of rediscovering all of the writing and research contained in the library took millennia, says Sagan, bemoaning the dark age that followed.

But the library’s fall was not as sudden or complete as is generally understood.

Richard Ovenden, director of the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford, writes in Burning the Books: A History of the Deliberate Destruction of Knowledge that the Library of Alexandria did weather fires, plural—“major incidents in which many books were lost”—during its existence. But these weren’t what felled the library.

Instead, contemporary scholars believe that its demise was actually slow and drawn out.

“A lack of oversight, leadership, and investment spread over centuries seems to have been the ultimate cause of the destruction of the Library of Alexandria,” Ovenden writes, arguing that the end of the great library can be seen as “a cautionary tale of the danger of creeping decline, through the underfunding, low prioritization and general disregard for the institutions that preserve and share knowledge.”

When the library did collapse, there had already been a dispersion of its knowledge across the ancient world. For instance, the creation of central repositories of knowledge, “while perhaps new to Greek tradition” with the creation of the Library of Alexandria, “was age-old in the Near East,” according to the 2019 study “Libraries before Alexandria: Ancient Near Eastern Traditions.” And it was thanks to these centers of learning that after the fall of Alexandria, scholars continued the work of collecting, translating, and sharing texts.

“Historians today are clear that there was no ‘dark age’ following the destruction of the Library of Alexandria,” Ovenden writes. “Knowledge continued to be gathered and learning flourished across Europe, Asia, Africa and the Middle East in continuation of the work undertaken at Alexandria and other centers.”

In The Map of Knowledge: How Classical Ideas Were Lost and Found: A History in Seven Cities, historian Violet Moller turns Euclid’s Elements, Ptolemy’s The Almagest, and Galen’s 3-million-word treatise on medicine into case studies of how key texts were not just preserved after the fall of the Library of Alexandria, but questioned and improved upon—“filtered through the minds of generations of scribes and translators, transformed and extended by brilliant scholars in the Arabic world, who in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance were gradually written out of history.”

But for the works that did ultimately vanish, the Christian Church’s campaign to suppress knowledge was aided by a major culprit: changing technology. Papyrus scrolls, upon which the library’s texts were recorded on, were infamously fragile and flammable. While the rise of parchment in the 3rd century C.E. led to a more secure record, it was also the likely cause of the disappearance of notable works, like the writings of the Greek poet Sappho. Contrary to the narrative that they were successfully destroyed by the Church, Ovenden writes that they were “probably lost when the demand was insufficiently great for them to be copied onto parchment.”

In a historical quirk, it was the competition between the library of Alexandria and the library of Pergamon, off the shore of Anatolia in modern-day Turkey, which may have sped up the age of parchment. Classicist Lionel Casson, who recounts the rivalry between the early libraries in his book Libraries in the Ancient World, notes the animosity that existed between Alexandria’s Ptolemy V and Eumenes II, whose reign is said to have overseen the construction of the library of Pergamon. Anecdotally, the story goes, it was when “Ptolemy stopped the export of papyrus … [that] the Pergamenes invented parchment.” Pointing to the long tradition in the Near East of writing on leather, Casson dismisses the idea that Pergamenes “invented parchment.” However, he suggests that “what they might have done was to improve the manufacture of leather skins for writing and increasingly adopt their use, moves that could well have been triggered by the desire to reduce Pergamum’s dependence on imports of Egyptian papyrus paper.”

Today, as we begin to mourn the end of the golden era of streaming, the Library of Alexandria offers a cautionary tale of how poor leadership, sustained neglect, and changing technology can cause an information collapse. But the library’s fall is not just a reminder of how an ambitious project to connect a world’s collections can falter. It also offers us hope that a collapse of information is never as sudden or as complete as it might seem at first.

As the embattled Arrested Development reminds us, there’s always money in the banana stand.

Send A Letter To the Editors