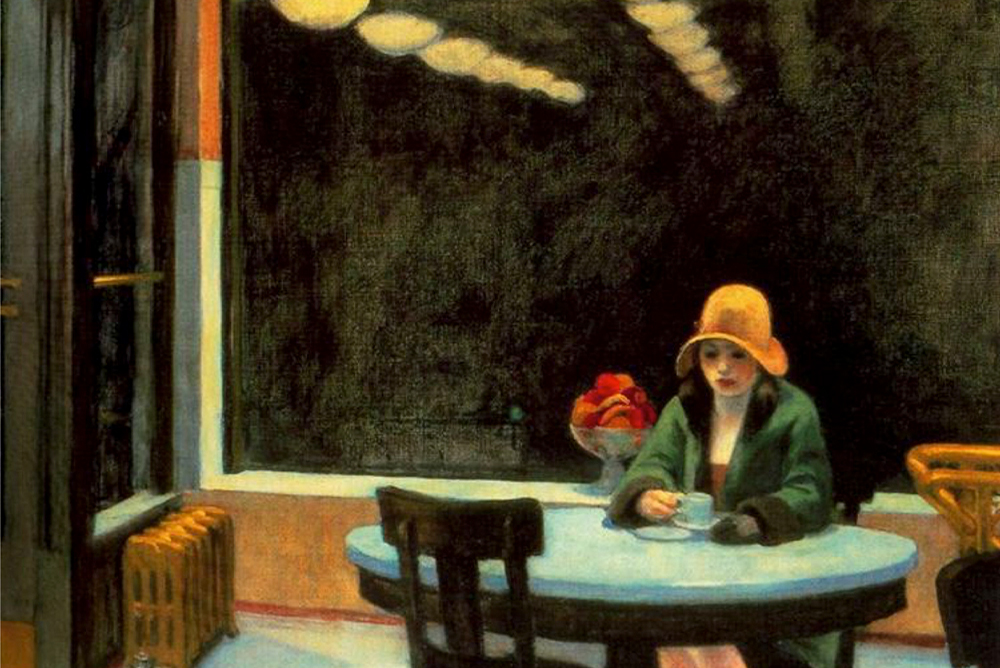

This Valentine’s Day may be the perfect time to re-examine loneliness. Columnist Jackie Mansky explains. “Automat” by Edward Hopper, 1927. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Can the 21st century forge a better relationship with loneliness?

It’s a question that feels especially appropriate on Valentine’s Day, the holiday most linked to the lonely-hearted.

Over two decades since Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone sounded the alarm bell on social isolation, and almost three years since COVID lockdowns began, we regularly speak about an epidemic of loneliness in the U.S.

But for all its ubiquity, loneliness remains relatively taboo. As psychiatrists Jacqueline Olds and Richard S. Schwartz observed in 2010’s The Lonely American, this nation, especially—and its obsession with self-reliance—has created a culture of shame around what is an “ordinary human emotion.” So much so that they noted most of their patients “were more comfortable saying they were depressed than saying they were lonely.”

But what if we considered the other side of the loneliness coin?

“I’m quite fascinated by loneliness. It can be really beautiful when you turn it over,” the Canadian singer and songwriter Carly Rae Jepsen muses in the introduction to her latest album, The Loneliest Time, which samples different flavors of loneliness—from the breezy brutality of “Beach House” (a bop about trying to find a connection on dating apps, the hook goes: “I’ve got a beach house in Malibu, and I’m probably going to hurt your feelings”) to the lead single, “Western Wind,” which Jepsen wrote after losing her grandmother.

The album, born out of the global pandemic, was what first got me thinking about how narrow our cultural framing around the subject remains.

But that’s slowly changing. The Loneliest Time is part of an emerging body of art and scholarship that could help us imagine a wider story around loneliness in the U.S. and around the world.

Until recently, the origins of loneliness were not a major topic of inquiry. “The history of loneliness is fundamental to understanding its prevalence and meanings in the 21st century. And yet this history has been virtually neglected,” noted sociocultural historian Fay Bound Alberti in her 2019 work, A Biography of Loneliness: The History of an Emotion.

Bound Alberti dates the thing we call “loneliness” today back relatively recently, to the 1800s when the term “loneliness” shifted in use from referring to physical distance—like how far you lived from town—to the emotional state associated with a perceived lack of company.

This change in meaning was not just a linguistic quirk. Modern loneliness, Bound Alberti argues, could only arise within a certain set of conditions—its invention dependent on “the formation of a society that was less inclusive and communal and more grounded in the scientific, medicalized idea of an individual mind, set against the rest.” It was the “philosophical and spiritual framework” of the industrializing world, then, which allowed for the condition of loneliness to take off.

That being said, as Amherst College’s Amelia Worsley writes in the forthcoming Routledge History of Loneliness, while loneliness “could not have always signified what it does today” the “complexity of early references to loneliness” is also understudied. The more we learn about it, the more some scholars of earlier periods are starting to argue that throughout history “there has always been something like the experience that is today called loneliness.”

The Routledge History of Loneliness includes research from scholars like Hannah Yip and Thomas Clifton, experts in Renaissance-era British literature who recently held a digital conference exploring early modern loneliness. The online meeting examined how historical subjects’ views on the subject compare to our own today. Just like now, Yip and Clifton concluded after the panels wrapped, loneliness was “a symptom of a system which at times alienates, isolates, or side-lines individuals.” And just like now, the balms for it were “compassion and community,” they wrote, quoting the 17th-century poet and priest George Herbert’s poem “Denial”: “They and my minde may chime / And mend my ryme.”

Afer reading that, I thought about how Jepsen said something similar when promoting The Loneliest Time. Author and critic Hanif Abdurraqib had noted on his podcast that listening to the album “there wasn’t any shame around loneliness or the idea of loneliness or the realities of loneliness, but it also wasn’t some finger-waggy thing—‘You just got to be good at living alone.’”

“I don’t think loneliness, the cure for it, is being really good at being alone,” Jepsen agreed. Instead she found that experiencing loneliness was what pushed her to seek out connection. “Reaching for that is what I wanted from this album,” she said. “I think that’s why it has a hopeful spin on it. It’s not ‘Be OK on your own.’ It’s natural to want to reach for people; we should. That’s what life is about. So let your loneliness make you brave.”

The more we understand the history of loneliness, the more we can start to see loneliness as a force like any other—one that, if we let it, can push us toward introspection and action and community. Just like 500 years ago, when the balladeers sang about being alone, today in an even lonelier time, works like The Loneliest Time should be taken as an invitation: to embrace this tangle of emotions and let it help connect us to the larger human experience.

Send A Letter To the Editors