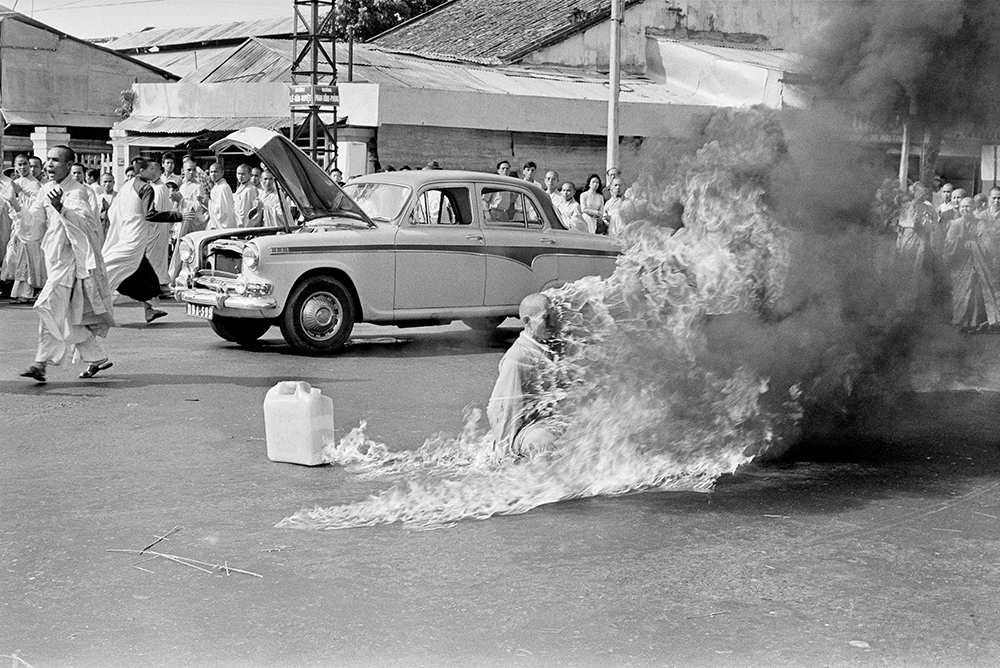

Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc’s self-immolation during the Vietnam War, captured by journalist Malcom Browne, left an imprint on the public conscience. Author Ray Boomhower explores the story behind the iconic photo and its lasting effects. Courtesy of AP Newsroom.

While President John F. Kennedy was talking by phone with his brother, U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, on the morning of Tuesday, June 12, 1963, he suddenly exclaimed: “Jesus Christ!”

The president’s outburst had nothing to do with their conversation. Rather, he was responding to a photograph taken the day before, splashed on the front pages of the newspapers just delivered to him. The photo showed 73-year-old Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc engulfed in flames on a street in Saigon, South Vietnam while sitting calmly—it seemed—in the lotus posture. He hoped his drastic action might bring the world’s attention to what the Buddhists saw as the persecution against their religion by the Catholic regime of President Ngo Dinh Diem. Buddhist organizations had called for freedom from arbitrary arrest, the right to assemble in public, and an end to the supposed Catholic bias in appointing government officials.

Captured by Malcom W. Browne, the head of the Associated Press’s bureau in Saigon, the photo retains its ability to stop conversations to this day, making it an enduring symbol of the power of protest. Meanwhile, critics insist that the photo, and the reporting from Vietnam by Western newsmen including Browne, David Halberstam of the New York Times, and Neil Sheehan of United Press International, were responsible for Diem’s downfall and America’s ultimate defeat and humiliation in Vietnam.

But Browne had been determined, he insisted, only to provide his readers with a “continuous, honest assessment of the situation” in what he called “a puzzling war.” He believed that officials in Vietnam—Americans and South Vietnamese—should have tried to do the same. Browne thought that living in a free society meant a journalist had to “tell all of the people all of the truth all of the time. The newsman is obliged to fight forces that interfere with this vital process.”

Criticism continued to follow Browne. Later, when he reported on the war in the Persian Gulf in 1991, detractors back home accused him of harming the American cause in its fight against Iraq. “This is just silly, of course,” Browne said. “To the extent that America newsmen ‘took sides’ in either Viet Nam or the Persian Gulf, it was on the side of the United States.” For all societies at war, the important truth, he suggested, was the truth “that tells you ‘we are the good guys and we are winning,’ regardless of what team you’re on,” reflected Browne.

Yet as American involvement in Vietnam wound down, it no longer seemed possible “to believe in the goodness and rightness of our cause,” Browne noted. The public had been regularly promised by its government that there was “a light at the end of the tunnel”—yet victory never came. Instead of pointing fingers at the individuals who involved the country in the conflict, many in the United States decided to “blame the messengers—people like myself who had been sending back discouraging tidings of how bad things had been going,” Browne said.

The story of the monk’s self-immolation began on May 8, 1963, when South Vietnamese army and security forces had killed civilians protesting a new governmental decree outlawing the flying of the Buddhist flag on Buddha’s birthday in Hue. These killings sparked protests against the Diem government’s perceived anti-Buddhist policies.

Quang Duc’s fiery sacrifice was the latest of these protests. Thirty-two-year-old Browne captured it on a cheap, Japanese Petri-brand camera. Browne had arrived in Saigon on November 7, 1961. He had witnessed the U.S. military presence in South Vietnam grow from about 3,000 American military advisers when he arrived to more than 16,000 by the end of 1963. Tipped off about the demonstration the evening before, he was the only Western reporter on the scene to capture the horrific event on film.

The elder monk uttered no sound as the flames consumed his body, and did not change his position. But from his spot about 20 feet to the right and a little in front of Quang Duc, Browne could see that his “features were contorted with agony” and could hear moans from the crowd that had gathered to watch, as well as the ragged chanting from the approximately 300 yellow-robed monks and gray-robed Buddhist nuns who had joined the protest.

The newsman found himself “numb with shock” at the horrible scene. Though witnessing anyone commit suicide or suffer a violent death “is always a hard experience,” Browne later noted, “you can get used to it in war, but there was something special about this. It was kind of a horror.”

After about ten minutes, the flames died down and the monk “pitched over, twitched convulsively and was still.” Seemingly out of nowhere, a coffin appeared and fellow monks attempted to place Quang Duc inside. It was no use. The monk’s limbs, Browne recalled, “had been roasted to rigidity, and he could not be bent enough to fit in the casket. As the procession moved off toward Xa Loi Pagoda, his blackened arms protruded from the coffin, one of them still smoking.”

Browne’s film soon made its way from the AP bureau in Saigon to Manila with the aid of a “pigeon”—a regular passenger on a commercial flight willing to act as a courier to avoid censorship by South Vietnamese government officials. The photos were sent via the AP WirePhoto cable from Manila to San Francisco, and from there to the news agency’s headquarters in New York. There, the images were distributed to AP member newspapers around the world.

The reaction was immediate. While millions of words had been written about the Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam, Browne’s pictures possessed what the correspondent later termed “an incomparable impact.”

A group of clergymen in the United States used the photograph for full-page advertisements in the New York Times and Washington Post decrying American military aid to a country that denied most of its citizens religious freedoms. Vietnamese Buddhist leaders emblazoned the image on placards they carried during demonstrations. Officials in communist China used the image for propaganda purposes, distributing copies throughout Southeast Asia and attributing the monk’s death to the work of “the U.S. imperialist aggressors and their Diemist lackeys.”

When President Kennedy called Henry Cabot Lodge to the White House to discuss his ambassadorship to South Vietnam, the president had on his desk a copy of the monk photograph. “I suppose that no news picture in recent history had generated as much emotion around the world as that one had,” Lodge noted.

Browne’s photograph has become one of the iconic images of the Vietnam War, seared into the collective American conscience alongside two other AP photographs—Eddie Adams’s “Saigon Execution,” his graphic shot of a suspected Viet Cong guerrilla being summarily executed at point-blank range by a South Vietnamese police chief, and Nick Ut’s “Terror of War,” showing a naked, nine-year-old girl screaming as she runs down a road with her skin burned from a South Vietnamese napalm bombing that mistakenly hit her village.

Browne, who won a Pulitzer in 1964 for his reporting from Vietnam, was often asked if he could have done anything to prevent Quang Duc from taking his life. But Browne realized that it would have been fruitless to try to intervene. The monks and nuns gathered for the protest stood ready to block anyone who dared to interfere. When a fire truck appeared, some of the monks had leapt in front of their wheels to stop them.

Quang Duc’s sacrifice weighed on Browne, who died on August 27, 2012. “I don’t think many journalists take pleasure from human suffering,” he noted, but he did have to admit to “having sometimes profited from others’ pain.” Although by no means intentional on his part, that fact did not help, Browne noted. “Journalists inadvertently influence events they cover, and although the effects are sometimes for the good, they can also be tragic,” he said. “Either way, when death is the outcome, psychic scars remain.”

There were other deaths that Browne witnessed in Vietnam—losses that became mere “footnotes” in the history of the war compared to the “theater of the horrible” that Quang Duc’s sacrifice represented for his cause. Browne, however, never forgot them. He had learned during his career to deal with “the ugliest events of our times,” including keeping his wits as he observed the dead and wounded on a battlefield. Browne was able to do his job by “concentrating on the mechanics of news covering. I have the nightmares afterwards.”

Send A Letter To the Editors