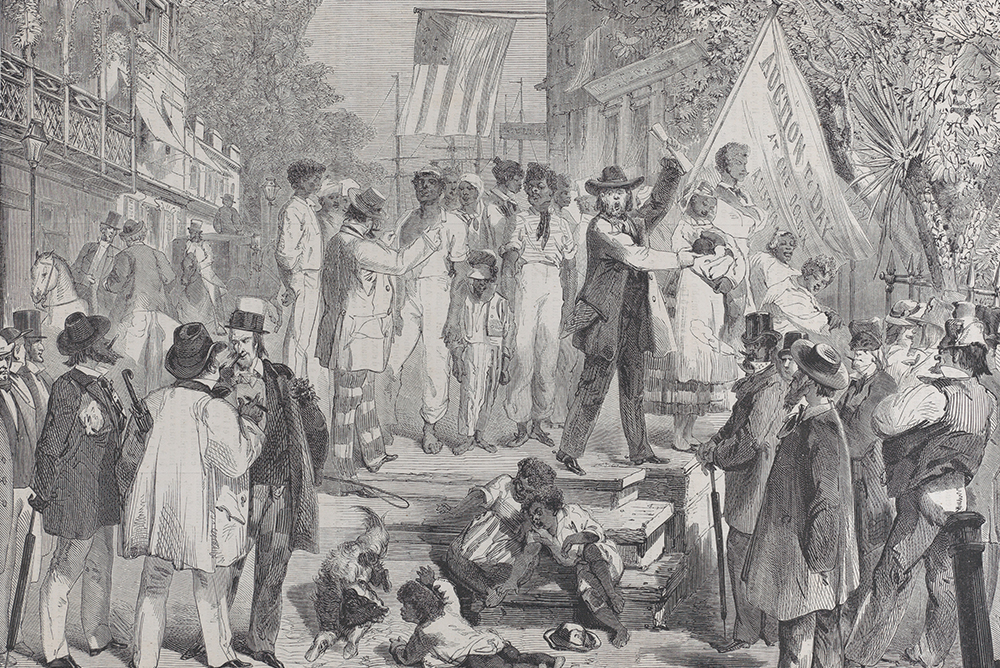

Historian Yesenia Barragan digs through the archives of abolition and into the sordid history of “gradual emancipation,” where, across the Americas, slaveholders were compensated for their “lost property.” Above is an illustration of a slave auction in Richmond, Virginia, printed in the “Le Monde Illustré,” a French weekly newspaper in 1861. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, public domain.

The records are difficult to make out at first—blurred rows listing the names of slaveholders, enslaved individuals, and prices under the dim light of the microfilm reader. But once brought into focus, they reveal a harrowing moment: enslaved men and women being appraised for the last time in their lives, a valuation made with abolition in service of direct payments to their former owners. There’s the record listing the enslaved man Santiago Servacio, possessed by the mistress Tereza Castaño, whose value was set at 9,900 pesos. And there are those described as “Many without names” (Varios sin nombre) claimed by Placida Colón for 2,000 pesos—likely elderly given their low assessment. Thousands more like these are stored away, accumulating dust in Colombia’s national archive, in the capital.

We often think of the abolition of slavery as a single, triumphant moment. But in reality, across the Americas, it was a slow process that was rife with concessions for slaveowners. The documents in Bogotá are one example of this. They are what historians call “compensation records,” which guaranteed government payment to former slaveholders to make up for their “lost property” after abolition. According to economic historians Jorge Andrés Tovar Mora and Hermes Tovar Pinzón, the Colombian treasury invested nearly 2.5 million pesos in compensating the former owners of 16,468 enslaved people after the abolition of slavery in 1852. The records are proof of the great lengths that governments went to in order to appease slaveholders.

Compensation to slaveholders after the abolition of slavery was the political consensus among elite powerbrokers across the 19th-century Atlantic World. After 1838, when the British crown abolished slavery in its Caribbean colonies, nearly 20 million British pounds were paid out to former masters. In Uruguay, which had a smaller enslaved population, an 1842 abolition law offered indemnification for owners. The French Revolution of 1848 terminated slavery in the country’s Caribbean colonies, again with compensation. Abolition with compensation swept the South American republics—Colombia, Ecuador, Argentina, Venezuela, and Peru—in the 1850s. The only exceptions to the rule were Brazil and the United States—save for Washington, D.C., which provided slaveholders loyal to the Union $300 for every enslaved person that was emancipated by the District of Columbia Emancipation Act of 1862, as historian Tera W. Hunter has shown.

But even before emancipation, compensation to slaveholders by other means had been taking place. Since the late 18th century, across the Americas, conversations about indemnifying slaveholders for their lost “property” were common when what were called “gradual abolition” or “gradual emancipation” laws started to be passed. “Gradual abolition” was a legislative approach to terminating chattel slavery through gradual, rather than immediate, means.

At the center of gradual emancipation legislation were what were called “Free Birth” or “Free Womb” laws, which sought to gradually end chattel slavery by terminating a long-standing cornerstone of slavery’s logic: partus sequitur ventrem, or the idea that a child’s status as slave or free derives from that of the mother. The Free Womb laws declared that the children of enslaved women born after a specific date would be freed either immediately or after serving their mother’s master for a particular period.

In 1780, the state of Pennsylvania was the first government in the Americas to adopt such a law—“An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” emancipated “Free Womb” children upon reaching the age of 28. It became the blueprint for future gradual emancipation models, followed by Connecticut and Rhode Island, which passed similar laws in 1784. During the Wars of Independence against Spain, the revolutionary governments of Chile and Argentina adopted gradual emancipation laws in 1811 and 1813, respectively. And when the newly christened Colombian republic approved its gradual emancipation law in 1821—in part inspired by these precedents—it legally “freed” the children of enslaved women born after the law’s promulgation, but it kept these children bonded to their mothers’ masters until the age of 18. This decision was the result of incredibly contentious debate, and the question of compensation to slaveholders was at its heart. Colombian statesmen struggled to come to an agreement about the length of bondage that would provide slaveholders with adequate recompense for their eventual loss of their human “assets.”

From late June to mid-July 1821, over 45 delegates from Colombia’s prosperous late-colonial elite debated the composition of the Free Womb law in what would become known as the Congress of Cúcuta. In his opening remarks to the congress, lawyer and author of the gradual emancipation law José Félix de Restrepo argued that Free Womb children’s labor could provide ample compensation to their owners if they were emancipated at age 16 or 18. As part of his argument, Restrepo presented an account of the “standard” life cycle of an enslaved person in their early years, a racial arithmetic that reflected the profoundly violent commodification of Free Womb children.

According to Restrepo, the first two years of an enslaved child’s life imposed little economic burden on the master. As the child aged and their expenses increased, so did their potential productivity. From ages 9 to 12, the enslaved child could perform small but important domestic tasks. Once they reached the age of 12, the youth was considered ready for hard labor, however defined by the individual master; this meant, Restrepo claimed, that masters could retrieve at least double their investment by the time the child reached the age of 14. From 14 to 18 years of age, the investment would quadruple. Slaveholders would consequently be handsomely indemnified for their eventually lost human “properties.”

Other congressional delegates disagreed with Restrepo’s assessments. Delegate Domingo Briceño y Briceño, who argued that the emancipation law would ultimately bring the republic’s downfall, used his own racial accounting to support extending the Free Womb children’s age of bondage. He claimed that masters expended nearly 400 pesos from the moment of an enslaved person’s birth to the age of 8, while they could only produce 144 pesos for their owner from ages 8 to 16, not even half the master’s investment.

After much deliberation, Colombia’s delegates voted 28-17 to set the age of emancipation for Free Womb children at 18. Their gradual emancipation law would serve as a model of white abolitionism with compensation to slaveholders across the continent. In 1824, for example, a few months after the Demerara Rebellion, a massive slave uprising that took place in Britain’s colony in present-day Guyana, Britain’s Marquess of Lansdowne petitioned the House of Lords to pass an abolitionist measure by calling attention to how, in Colombia’s “provisions for the gradual extinction of slavery[, …] care had been taken to secure to all parties compensation for loss.”

As though having benefited from human property for centuries were not enough, freedom for the enslaved people in the Americas came with compensation to slaveholders—first in the form of Free Womb laws, later in direct payouts. It forces us to understand the plentiful ways that slaveholders received reparations during the gradual and final abolition of slavery. The struggles of formerly enslaved people and the enduring stranglehold that slaveholders had over them make clear the need for reparative justice for people of African descent across the Americas. For the thousands of Free Womb children across Colombia and the Americas that were the test subjects of gradual abolition. And for the enslaved men like Santiago Servacio and the “Many without names” whose paper bodies fill the archives of abolition.

Send A Letter To the Editors