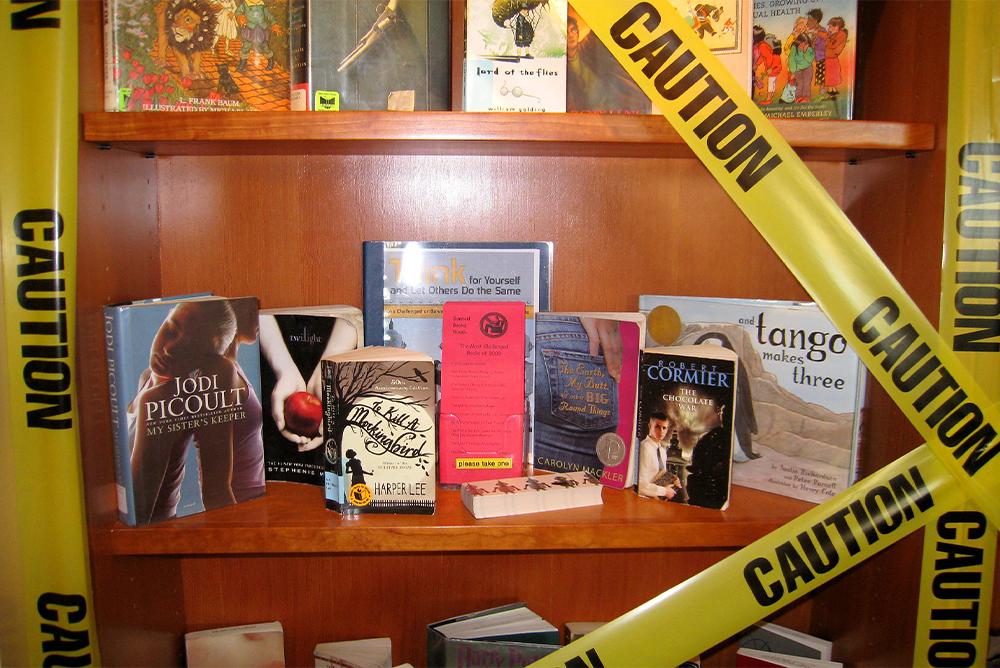

Across California, and the country, books are being censored. Could these bans make books dangerous—and fun again? Columnist Joe Mathews opines. Courtesy of San José Public Library/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Ban this column! Please!

It might seem strange to call for the cancellation of one’s own newspaper column. Besides, who needs to squelch such a piece when media audiences are declining already?

But my request is no stranger than the logic driving efforts to ban books that children might read—in California, and in schools and libraries around the country.

Surveys, in the U.S. and around the world, show children and teens are reading fewer books, and enjoying their reading less, than in decades past. The National Assessment of Educational Progress found the percentages of American 9- and 13-year-olds who read for fun are at their lowest levels since 1984. And that shouldn’t surprise us, given all the hours that young people spend on their screens.

Yet, bizarrely, this moment has become the time for culture warriors, mostly on the right, to demand the banning or removal of books. They have targeted more than 2,500 titles, according to the American Library Association. Even more gobsmacking are the reasons parents and others seeking these bans cite: They want to prevent kids from learning about some of the most talked-about issues in our society—especially anything related to identity, gender, sexuality, or sex.

Of course, the true reasons for banning books go beyond misguided notions of childhood protection. Book bans are tied to organized efforts to demonize LGBTQ+ people, and to score political points by appealing to resentment of educational elites.

You can see both strategies in play at the Temecula Valley Unified School District, whose board of education overruled district staff and voted to ban a social studies textbook, part of the elementary school curriculum, which touched on gay rights topics. In doing so, board members called the late San Francisco supervisor and gay rights pioneer Harvey Milk a “pedophile.” They later fired the popular district superintendent.

State government answered this culture war blast with a bomb. Gov. Gavin Newsom denounced the board members as “malicious actors” and threatened “legal repercussions.” State Attorney General Rob Bonta launched an investigation. And the state legislature advanced a bill that would make it harder to ban textbooks, setting up an appeal process at county boards of education.

Such official action, reinforced by local teacher and parent protests against the board members, was understandable. But the top-down reprimands also felt like a missed opportunity—to provide children and young people a compelling reason to pick up a book and read.

When it comes to bringing the fascinating California drama of gay rights to life, we can do better than a textbook. If I were the governor or attorney general, I’d slow down the public denunciations—which mostly seemed to gain more publicity for the board members—and instead send every household in Temecula a copy of Randy Shilts’ terrific 1982 biography of Milk, The Mayor of Castro Street.

Yes, we should challenge book bans. But, even more urgently, we should seize upon them to get people reading. A number of librarians are doing just that—setting aside special shelves and stacks of banned books. So are booksellers: The best-known banned books have seen big boosts in sales.

Bans can make books dangerous—and fun again. As the novelist Katherine Marsh recently wrote in the Atlantic, this era of standardized curricula eschews the most captivating books, with unforgettable characters. Instead, teachers hand students short excerpts and ask for literary analysis. How appallingly boring.

If we want to engage students, we should have them read books that grab their interest—whether because they’re forbidden or messy or find beauty in surprising circumstances. And special attention should go to steering students toward readable and compelling books about love, gender, sexuality, and sex, which are elemental, humanity-affirming aspects of life.

If such reading encourages actual sex, as the book banners fear, our society might be better off for it. Just as book reading has declined, so has sex among people, especially young adults, in the U.S. and around the globe.

According to UCLA, the percentage of Californians ages 18 to 30 who reported having no sexual partners in the past year jumped from 22 percent in 2011 to 38 percent in 2021. People are increasingly isolated, and isolation poses a public health problem. Sexual activity—the form of human connection upon which our species depends for its survival—can boost mental and physical health, happiness, and quality of life.

Your columnist is old enough to remember when books and sex, and the leisurely enjoyment of both, were what summer was all about. This time of year was for shedding our American Puritanism—and our clothes, and giving in to desires for beach reads and romance. (If only Americans could repurpose their puritanical fears of sex into righteous limits on guns and the violence they cause.)

So, this summer, let’s screw the censors. Read some good books—see lists of the most banned titles for ideas (I recommend The Perks of Being a Wallflower). And while you’re at it, get cozy with a person, too.

And if you don’t have a book lying around, perhaps you and that special someone might find reading this column romantic. Especially once it’s banned.

Send A Letter To the Editors