Why is so much federally owned land in the American West inaccessible? Anthropologist Julia Sizek explains how “checkerboarding”—alternating parcels of private and public lands—came to be, and why it’s a persisting problem. Courtesy of The Wildlands Conservancy.

The West has a checkerboard problem.

According to the company behind the popular hunting app OnX, 530,000 acres of public lands in California alone are inaccessible to the general public. That’s because they alternate with privately owned lands in the shape of a checkerboard.

It’s easy to see the checkerboard and its inaccessible public lands just by looking at a road atlas. The western Mojave Desert, the swath northwest of Lake Tahoe, and the area between Redding and the Oregon border all have alternating square-mile checks of private and public land. But it’s often invisible on the ground because no fences or visible property lines mark the change in land tenure. If private landowners choose to restrict access across their property, as they have in popular hunting areas in Wyoming and Montana, the public can be prosecuted for trespassing if they pass through to get to the adjacent public land—even if they “corner-cross,” moving diagonally between the squares.

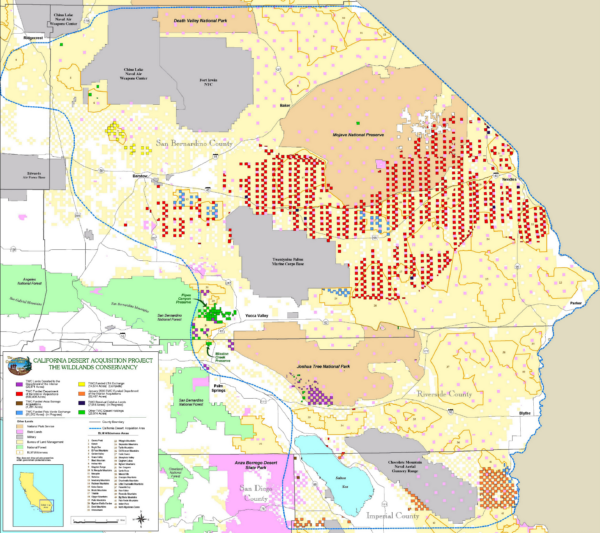

Can the public get access to these lands back? In the eastern Mojave Desert, where I’ve conducted research for a decade, the land ownership map remained a checkerboard until 2000, when a groundbreaking purchase added over half a million acres to the public domain. But while this deal improved access to the California desert, it took more than five years of negotiation to achieve. Even with willing sellers, buyers, and millions of dollars on the line, it shows that public access is nearly impossible to secure in a system that privileges private property.

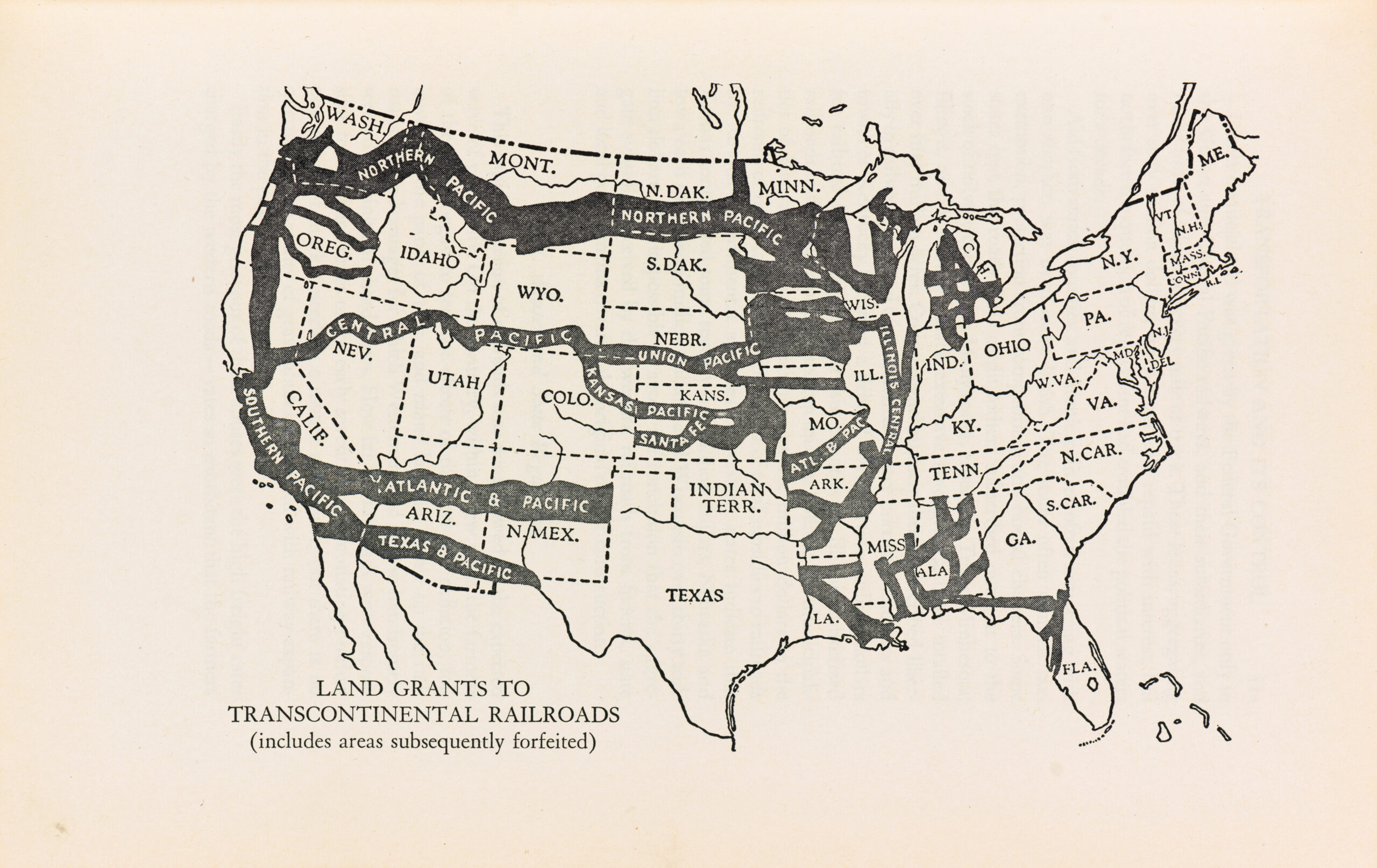

The checkerboard came about in the 1880s, when the federal government—which had claimed California as its own by dispossessing Indigenous peoples—gifted every other square-mile section along the region’s transcontinental corridors to railroad companies. Congress saw the checkerboard as a novel solution to a practical problem: how to help finance transcontinental railroads without paying for them in gold. By checkerboarding the land, the government ensured that the railroad companies couldn’t sell it to rich landholders in large parcels. The people behind these deals likely imagined that the checkerboard would quickly disappear into a landscape of small homesteads, keeping Thomas Jefferson’s agrarian dream alive while settling the West.

A 1942 map exaggerated railroad land grant holdings. Courtesy of Cornell University – PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography.

Things didn’t go according to plan. In high-value timber areas in Oregon, railroads worked with so-called “dummy entrymen” to file for the alternating public lands sections, consolidate landownership for the railroad, and sell the lands at high prices to large lumber interests. In low-value areas like the Mojave Desert, meanwhile, no settlers wanted to buy the land. Railroad historian David F. Myrick estimated that in San Bernardino County alone, 853,265 acres remained in railroad hands in the early 20th century.

By the 1970s, the federal government—like the railroad—had largely given up on the project of selling lands to homesteaders. With the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, it moved to permanently retain public lands rather than trying to sell them off. But that didn’t get rid of the checkerboard—the private squares remained in the hands of landowners, posing a problem for federal land management agencies. When Congress created the Bureau of Land Management’s East Mojave National Scenic Area in 1976, for instance, parts of its boundaries surrounded a dense swath of checkerboard, which prevented the agency from building access roads or making improvements to those areas.

This came to a head in 1994, when the California Desert Protection Act changed the East Mojave National Scenic Area into the Mojave National Preserve and handed it over to the National Park Service.

After decades of ignoring its desert lands, the Catellus Development Corporation, the company that had taken over the Southern Pacific Land Company’s holdings, sent teams to survey its lands for minerals and development opportunities, and put up large “For Sale” signs. Conservationists feared that this would result in widespread development across the desert, negating the work that they had done to pass the Desert Protection Act.

The federal government tried to strike a deal with Catellus, and failed. Then, a land trust called the Wildlands Conservancy stepped in to broker a deal. But nothing like it had ever been done before: How would a non-profit go about purchasing a half-million acres of land in a checkerboard?

By 2003, the Wildlands Conservancy acquired over half a million acres of desert land from Catellus Development Corporation, much of it “checkerboarded” decades before. Courtesy of The Wildlands Conservancy.

Even simply surveying the purchase posed a major hurdle—it necessitated someone check all that land—more than 0.5% of California—for dumping, hazardous materials, and development.

Wildlands decided to use aerial surveys, but GPS was still a relatively new technology, and prone to user error. One of the Wildlands’ former employees told me that the first flight ended up being a full quarter-mile off, because the GPS was using the wrong map projection.

In the end, slightly over 100 of the 631 parcels that were part of the acquisition required environmental remediation to clean up dumping and remnants of mining and squatting. Some of the parcels—including one that was part of a railroad “Y” where trains turned around—were so degraded that they couldn’t be remediated in time for the sale.

By the end of 2003, Wildlands had acquired a final total of 560,831 acres of desert land from Catellus. Through a combination of Land and Water Conservation Funds sales and donation, Wildlands turned these lands over to the federal government to become part of the Mojave National Preserve. The massive purchase kept open access to 3.7 million acres of public land that could have easily been eliminated by private landowners.

The purchase was possible, in part, because the acquired lands were surrounded by areas with conservation designations, or recognized as critical habitat for the federally listed desert tortoise. When areas don’t have such designations, it’s harder for land trusts to purchase land, because they have to make a case for their conservation value. It’s especially challenging to justify lands as conservation purchases if they have already been developed or mined.

The most important factor in the Mojave National Preserve deal, though, was that Catellus was willing to sell. That isn’t the case for many of the remaining checkerboards today, which are smaller than they were in the 1990s, owned by more people, and more entrenched as private land.

Of course, that hasn’t stopped groups like the Mojave Desert Land Trust from trying. Each year, they reach out to thousands of owners of land in the East Mojave to try to convince them to sell their lands. But their transactions are tiny in comparison to the Catellus deal, averaging around 100 acres per purchase, and many people just aren’t willing to sell.

Without intervention from Congress to sell or trade other federal lands in exchange for checkerboard lands to ensure the right of public access to all public lands through easements or condemnation or to designate checkerboarded areas as having conservation value, hundreds of thousands of acres of public land aren’t likely to become accessible anytime soon. As long as the checkerboard persists throughout the American West, 19th-century railroad robber barons continue to deny the public access to federally owned lands.

Send A Letter To the Editors