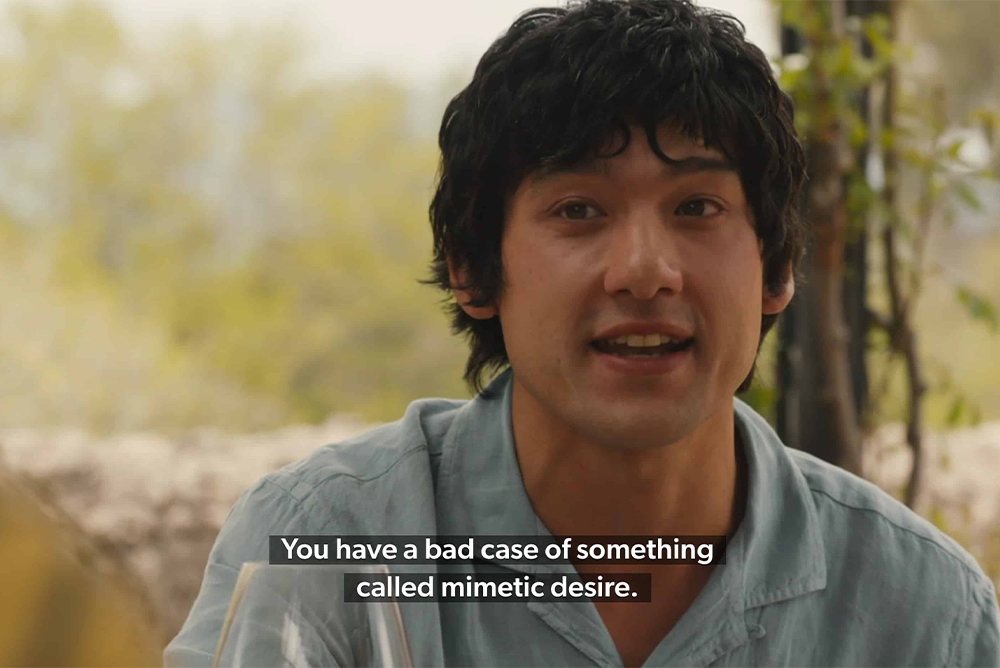

Philosopher René Girard’s theories on desire and envy have entered mainstream culture, showing up in places like HBO’s The White Lotus (above). In what would have been Girard’s 100th year, scholar Cynthia Haven reflects on his teachings for humanity. Courtesy of HBO/The White Lotus.

Years ago at a conference, French theorist René Girard faced a tough question about his unconventional methods.

The Stanford professor’s research involved a close reading of archaic and classical texts from Greece, Rome, Mesopotamia, and elsewhere—which is to say, a close reading of ancient stories. In these stories, he discerned hidden patterns of rivalry, and how we use collective violence to end strife, an unending sequence throughout the long night of humanity.

“Given that we can’t entirely trust the veracity of ancient writings,” one academic asked him afterwards, “how would you measure the success of your theory?”

Girard’s answer was a thunderbolt: “You will see the success of my theories when you recognize yourself as a persecutor.”

That is one unpleasant, but practical and productive, takeaway from Girard’s theories. It should give us pause and prod a moment of self-reflection.

Girard’s writing was seasoned with humor and insight—for he had learned something about himself along his journey, and so didn’t offer himself as a hero or an answer. He saw an ominous world of scapegoats and persecutors. His worldview has important implications for each of us, and how we live every day of the rest of our lives.

Girard, who died in 2015, has been resonating with large swaths of the culture, because his messages about envy, competition, and violence are timely and timeless. References increasingly pop up in unexpected places, from the HBO show The White Lotus to a recent New York Times crossword puzzle.

Girard, who didn’t crave the limelight, would have been amused by this posthumous attention, which is sure to compound with the celebrations marking his 100th birthday, on Christmas Day.

Already, in June, he was fêted at an international centenary conference for more than 250 people at the Institut Catholique de Paris. Other events are planned in other cities—Washington, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Over at Stanford, where Girard was the inaugural Andrew B. Hammond Professor of French Language, Literature, and Civilization, a seminar on the campus in July is being organized by the University of Chicago’s Lumen Christi Institute.

The most enduring souvenir of the centenary year may be this: Three years ago, Penguin Modern Classics invited me to create a volume of his essential writings; All Desire is a Desire for Being was published in June. He is the only Stanford scholar to be so honored since Wallace Stegner almost four decades ago. The volume has been heralded with hundreds of preorders, Facebook posts, and retweets on Twitter.

William Johnsen of Michigan State University Press—which published Girard’s final book Battling to the End as well as my 2018 biography, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard—said at the Paris conference that the book marks a turning point: “Penguin books has been the most successful venture in gaining a wide audience for serious books in English for the last one hundred years. Nothing else even comes close … this is a big deal, so buckle up.”

Girard’s public life began in literary theory and criticism, with the study of authors whose protagonists embraced self-renunciation and self-revelation. Eventually, his scholarship crossed into the fields of anthropology, sociology, history, philosophy, psychology, and theology.

Let’s review some of his more important conclusions.

René Girard at a colloquium in 2007. Courtesy of Wikimedia commons. Public domain.

Girard overturned three widespread assumptions about the nature of desire and violence: first, that our desire is authentic and our own; second, that we fight because of our differences, rather than our sameness; and third, that religion is the cause of violence, rather than an archaic solution for controlling violence within a society.

Where does conflict begin? According to Girard, it begins with envy. We think our desire is something innate, that comes from ourselves, but it’s not true. Others show us what to want. Desire is a social phenomenon, and it is contagious. We want what others want. We want it because they want it. And we will admit to almost anything before we admit to our envy, which is a confession of our inner poverty. Girard marveled at how little we talk about envy. He said: “You cannot talk about your envy. I think the reason we talk so much about sex is that we don’t dare talk about envy. The real repression is the repression of envy.”

But not always. The American novelist Gore Vidal expressed it wryly this way: “Every time a friend succeeds, something dies inside me.” That’s one good remedy: Laugh at it. Strip envy of its power. If you can make a joke of your envy, some part of you isn’t under its sway.

Envy puts us in competition with others. We are drawn to those whom we imagine are more of what we long to be—and the more we are attracted to them; the more they sense our covetousness, our competition, and up the ante, or push us away. Shakespeare’s comedies abound in these plots.

“We move always to the greatest strength in the direction of the desire we envy most,” Girard said. “We do so because that power is greater than ours—and it’s probably going to defeat us again.” Hence, we are pulled into masochistic relationships with each other.

Our competitive and covetous quest for jobs, sex, power, perks, political clout, or an entrée into the elite clique spread contagiously through society—everybody imitates, and so they want the same things. This leads us to conflict and ultimately escalation—snubs, sackings, social banishment, and violence.

It’s easier when the models for our desire are far away—when Don Quixote becomes enamored of Amadís de Gaul, a chivalric knight of old, there is no chance of violent confrontation; the fictitious knight was long dead, and never existed anyway. But the closer a rival is to us, a brother or best friend, the more heated the competition, the less one can remain aloof, and the more the other resists our attempted appropriation. Our exchanges become prone to vendettas and reprisals.

Hence, Girard observed that we fight not because of our differences, but because of our sameness. Entire communities can be absorbed into the escalating competition and retaliation. Think of our political parties. Think of our wars.

That imbroglio is resolved, since time immemorial, by a scapegoating event that finds a target in someone or some group that cannot or will not retaliate, those who can plausibly be blamed for all the troubles. The target is someone marginal, an outsider who cannot fight back, or someone so far above us that they stand alone. A beggar or king, a president, a zillionaire, a foreigner, or a persecuted minority.

That target is killed, exiled, or otherwise eliminated. This murder expels enormous energy and restores social calm. The scapegoat has the seemingly magical power to bring peace, and becomes seen as a sort of deity, the foundation of new community. “There is no culture without a tomb and no tomb without a culture,” Girard said. He claims that the memorializing of this scapegoat—who brought peace after all—is the birth pangs of archaic human culture, but it is also a page from the diary of our everyday lives. We are all persecutors, after all.

So, what is the way out? Girard’s books offer an answer. We must not retaliate; we must declare unconditional peace with our neighbors. The last sentences of his book The Scapegoat put it even more urgently than that: “The time has come for us to forgive one another. If we wait any longer there will not be time enough.”

To enter the cultural mainstream, as Girard has now, is an important landmark. But in his own words, the stakes are much higher than that. How do we deepen and extend the conversation he has started?

The final frontier is not outer space or artificial intelligence, but the space within us, our inner intelligence, what is most deeply human in us. René Girard made a call for universal forgiveness, for that unconditional peace with our neighbor. What does that even mean? How do we go about it? It’s a question I have pondered myself over the years, as I have wrestled with my own deep and ineradicable resentments.

“History is a test. Mankind is failing it,” he said. It sounds like apocalyptic, end-of-the-world stuff, but it has in fact immediate ramifications for all of us here, today, and in the coming century of Girard’s unfolding legacy.

Send A Letter To the Editors