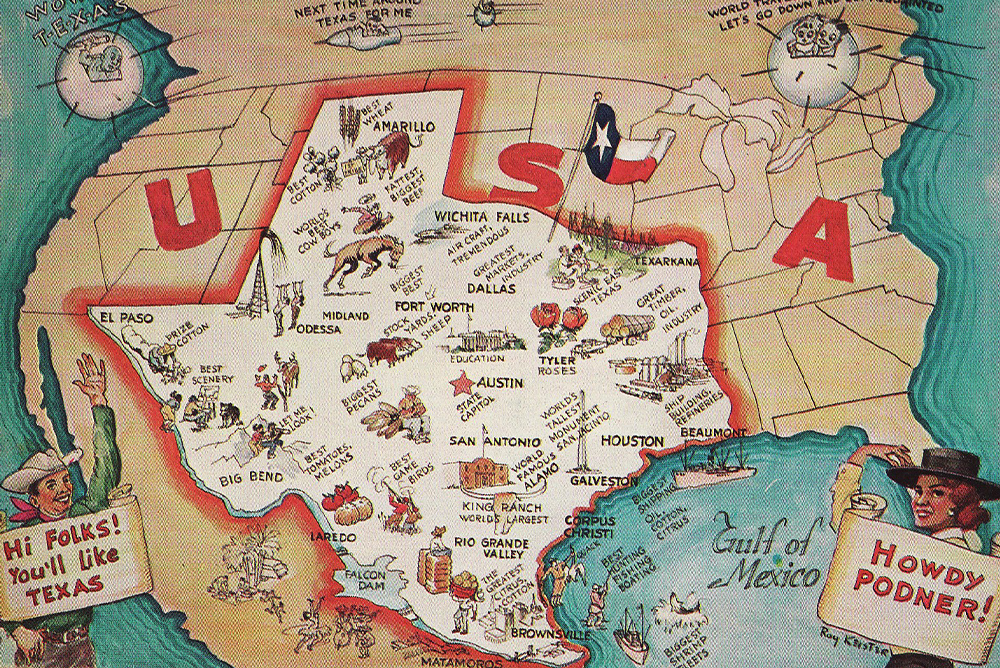

When did California turn over national leadership to Texas? Columnist Joe Mathews, reporting from the year 2049, points to events in 2023. Courtesy of Calsidyros/Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Austin, December 2049

Today, state officials held a massive parade and public barbecue to celebrate official federal confirmation that Texas is America’s greatest and most important state.

The occasion: The U.S. Census Bureau released estimates showing that the ever-growing Lone Star State, with more than 40.3 million people, had surpassed stagnant California, stuck at just under 40 million people for 30 years.

As Texans boasted about their new status—“We are the greatest civilization of the greatest country on earth,” declared 79-year-old U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz, now in his seventh term—Golden State leaders issued well-practiced denials.

“Population isn’t a true measure of greatness,” protested California Gov. Meghan Markle. “California is still the land of the grandest dreams, of the most embarrassing celebrities, of $10 million two-bedroom starter homes.”

But most longtime observers of the Golden State shrugged at Texas’ triumph.

Some noted that, as early as 2023, estimates from demographers predicted that Texas would surpass California in population by 2050.

In retrospect, 2023 was also the year it became obvious that California would willingly cede national leadership to Texas, signaling its surrender with a total lack of response to a startling and historic drop in population.

California’s population had always grown, often dramatically, ever since statehood. And when California passed New York to become the most populous state in November 1962, the moment launched an era in which the Golden State was seen as the nation’s leader in culture, economy, and policymaking.

That era started to end in the COVID-19 pandemic. From July 2020 to July 2022, it lost more than half a million people. Many pinned the cause on COVID deaths, and Californians leaving the state. But deaths and departures were part of the population decline.

The real problem was the lack of new Californians. The birth rate fell to a level that made old Europe look fertile. Immigration plummeted too, in part because of cruel and restrictionist federal immigration policies. And Americans all but stopped moving to California, with its rampant homelessness and expensive housing. How could they afford to?

In a saner time, such a rapid reversal of population in a state synonymous with arrival and growth—“California, Here I Come”—would have been considered a crisis. State and local governments would have come forward with new programs to encourage births, to keep existing Californians in the state, and to attract new ones. Budget surpluses could have been devoted to big new tax bonuses for starting families, to loan forgiveness for California university graduates who settled in the state after graduation, and to massive new affordable housing and infrastructure projects.

But 2023 was a very peculiar and unsettled time. People were depressed and anxious. Society was divided and in conflict. The public conversation, diminished by the decline of independent media, offered few visions of the future. Instead, the state and the country were consumed by loud and angry debates about racial and gender identity, and how to reinterpret the past.

So, Californians never seized on population decline as a reason to remake and rebuild the state.

And they never did the democratic math and recognized that losing population would mean losing power and influence.

Instead, Californians used population decline as an excuse not to do new and hard things.

This denial was most prominent on housing. Communities countered state pressure to build more housing by arguing that housing wouldn’t be necessary because there would be fewer people. This was a cynical bit of illogic—there couldn’t be more Californians without more housing—and it ignored the hard fact that California’s housing stock was the oldest in the West (and as old as housing stock in much of the Rust Belt).

But it worked. Media amplified the argument. State courts began embracing an argument that people themselves were pollution under the state’s main environmental law. And housing production, which had dropped by nearly half between the early 2000s and the early 2020s, continued its fall. The housing shortage became permanent, freezing California’s population at 40 million.

A similar dynamic froze California in other ways. With the population of children declining rapidly, school districts shut down schools and programs, instead of expanding educational offerings and building new schools to draw more kids. The state’s university systems, consumed by culture war and workplace conduct controversies, did too little to counter declines in enrollment. California’s powerful environmental groups and labor unions kept fighting efforts to build new, climate-resilient infrastructure in water, energy, and transportation.

The message sent by California to the rest of the world was clear: If we don’t build it, you won’t come.

And you didn’t.

In truth, today’s news on state populations was just the latest in a long series of declines. The Texas economy became bigger than California’s in 2040, which was not much of a surprise. Texas had been the nation’s leader in exports and renewable energy since early in the 21st century. For a couple of generations, Texas invested a higher percentage of its budget in education, and delivered better student outcomes, than California.

Meanwhile, the Digital Age ended the primacy of Hollywood and Silicon Valley. The entertainment and technology sectors could operate anywhere and no longer required headquarters in California, or anywhere else.

California’s slide down the economic rankings came quickly. In 2023, California’s governor liked to brag about the state becoming the world’s fourth largest economy. The state is down to 14th place today, and dropping.

Which leaves us with questions. If California had focused more on growth and the future back in the 2020s, could it have remained bigger and richer than Texas? Or could the state at least have forestalled its decline?

Maybe. But we’ll never know, because California never really tried.

Send A Letter To the Editors