Sheila Bird, a member of the Cherokee nation, uses her podcast, THPO Talk, to teach a new generation how to preserve tribal interests. Above, Bird (left) and co-host Deanna Byrd of the Choctaw Nation at the podcast’s first recording session, at the University of Oklahoma. Photo by Brian Burkhart. Courtesy of author.

I started working in repatriation efforts before I even knew what the term meant.

But repatriation—bringing our ancestors home—is in my blood. I grew up in a Cherokee community in Chewey, Oklahoma, in the foothills of the Ozarks. Sometimes I’ve wondered how my extended family could be as fortunate as we were, remaining isolated from the nearby towns, with a river running in front of us and a small creek behind. My relatives would tell me how much it was like our ancestors’ original home in the East, with mountainous terrain, ample water, and lush vegetation.

Over a century, my relatives fought for this Oklahoma home, traveling thousands of miles to push back against U.S. government overreach. Today, I continue the tradition by teaching a new generation of tribal officials how to work with the federal government to preserve what is ours. As a former “tribal historic preservation officer,” or a THPO, who reviews federal undertakings, it has been my job to step in when such projects threaten our sacred sites or our tribal interests.

My family’s land—where my grandmothers raised us—was a parcel that the U.S. government designated for individual Cherokees through the allotment process created by the Dawes Act of 1887. In the 19th century, allotment was presented as a way to “domesticate” us. I believe the real idea was to divide up families and scatter us about.

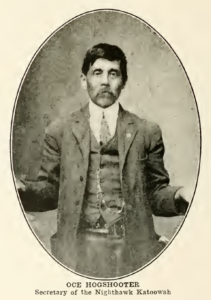

My great-grandfather, Osie Hogshooter, understood this. He had a significant role in an uprising against the allotment system, joining forces with Chief Redbird Smith, leader of the Keetoowah (Gi-du-wa) Nighthawks. The Nighthawks were traditionalists, full-blooded Cherokees who had made their way to Arkansas after ceding southeastern territory to the U.S. government in the late 1700s. They were distinct from the emigrant Cherokees who came to Indian Territory later, by way of the Trail of Tears, though both groups experienced forced displacement.

The Keetoowah Nighthawks knew that dividing our community would weaken our families, and the communal way of life that had sustained us through traumatic removals in the past. So a group of leaders, including my great-grandfather, who served as secretary, accompanied Chief Redbird Smith on a widely publicized journey to Washington, D.C., where they met with President Taft.

Unfortunately, the Nighthawks were not able to stop this moving freight train.

I learned about Osie’s participation in the Nighthawk campaign from my mother, Marie Bird, the only living person in our family who remembers him today, if vaguely, from when she was a little girl. She often spoke to me of the Nighthawks and all that they stood for. Osie refused his allotment, she told us, never living on it. When people filed to claim the land through squatters’ rights, we asked her, what do we do? She said, we do nothing—we stay away, just as Osie had. She always told me to stand up, and not to be afraid to speak my voice.

It wasn’t a stretch for me to get involved in a movement of my own, but I didn’t know what sort of movement it would be. I attended and graduated from an Indian boarding school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma; married, had three kids, worked taking care of my family.

As a young adult, I looked around our tribal communities and saw how divided we had become. Not just from family but from municipality. We didn’t have libraries. We didn’t have internet access. The rivers and creeks can only do so much for you, and we had to work for wages, but our job options were limited—chicken farms, manufacturing, any place within 30 miles each way. We shared rides, so you went to work where your neighbor did.

Stories about the Nighthawks lay dormant in my mind as I went through life’s struggles. If Osie, whose genes I shared, could educate himself about government and become a part of a movement to protect what is sacred to us, I could do the same.

Once my youngest child was a high school senior, I quit my job to enroll in the native studies program at the University of Oklahoma in Norman, something I had wanted to do since I was 18. I wanted to understand how the American government took over Cherokee lives and lands. I wanted to be able to explain why we were where we are, and how we got here, to my people back home. I wanted to continue the resistance.

A portrait of Osie Hogshooter, probably taken during his Washington, D.C. visit with the Keetoowah Nighthawk delegation. From The History of the Cherokee Indians and Their Legends and Folk Lore by Emmet Starr (1921) / Author collection.

In college, I learned about sovereignty, and about federal Indian law. In 1966, Congress passed the National Historic Preservation Act, a law designed to protect “our cultural footprint” during construction. But the Act excluded the tribes. Which was one of the reasons why, in the name of progress, the federal government routinely flooded valleys where our people had lived since time immemorial in order to build dams. Our bones have interstates on top of them now. Anything found during construction got whisked away and placed on museum shelves. Institutions held our ancestors in collections, against their will. Who would choose to be in a box, far from your homeland?

I graduated from college in 2012, and then began to work within and sometimes against the complicated system that was emerging to bring our culture and people back home. Things had begun to change—slowly. In the early ’90s, Congress amended the National Historic Preservation Act to include consulting tribes. It also passed the Native American Graves Protections and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, which allowed us to recover our ancestors’ remains from faraway institutions.

I found my movement, and made this struggle my cause.

In 2015, I became the first-ever tribal historic preservation officer, or THPO, for the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. I created a process to give us a voice on the 300 projects the federal government proposed every month that posed a threat to our cultural footprint. When the federal government proposed selling leases to build a transmission line through Cherokee and other tribal lands, for instance, we figured out a path through the regulatory thicket to prevent the project. It never got built.

Across the U.S., THPOs have figured out ways to save our cultural heritage. Working with other tribes, for instance, the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma developed a tribal monitoring policy for construction projects. Now, on certain projects, we accompany archaeologists working in historic preservation when they come in to determine what to save before a project. Things that signify a burial site for us might not be obvious to them. You take notes on what you see, we tell them, and we’ll take notes on what we see, and together we’ll come up with an agreement on how we’ll proceed with the project.

After two years, I left the Cherokee Nation to become a consultant to other tribes, to help them do this work. THPOs come from a wide range of backgrounds—we found our way here through different journeys, stumbling upon a job that we hadn’t even known was available. We are often overwhelmed by our workloads, by an alphabet soup of technical and legal acronyms we have to digest, by blanket U.S. government policies, and by the sheer number of projects that threaten to deplete our tribes’ cultural footprints.

Social media has lent a hand, creating a way for us to pool our experiences, but we have trouble communicating and educating on a broader scale. I searched high and low for a better way, and finally settled on a podcast to bring our tribal interests and landscapes together. “THPO Talk,” which I launched in the spring of 2022, connects preservation officers’ voices. We talk with federal partners, or any interested party who wants to understand our goals. Repatriation, international repatriation, historic preservation—we touch on it all. We support one another, and hope that in doing so, we will honor our ancestors, and assure our survival.

Our ancestors paid the ultimate cost, and paved the way for us to be resilient in this work. We’re telling our stories. We’re telling our grandchildren about the past and also about how to protect our future.

It wasn’t until I became a THPO that I went to Washington myself, to testify before a commission. While I was there, I found a Washington Post article that described my great-grandfather’s journey with the Nighthawks, more than a century earlier.

I wore moccasins that I had made myself. I looked down at my feet and I thought, I could be walking the same path Osie did.

Send A Letter To the Editors