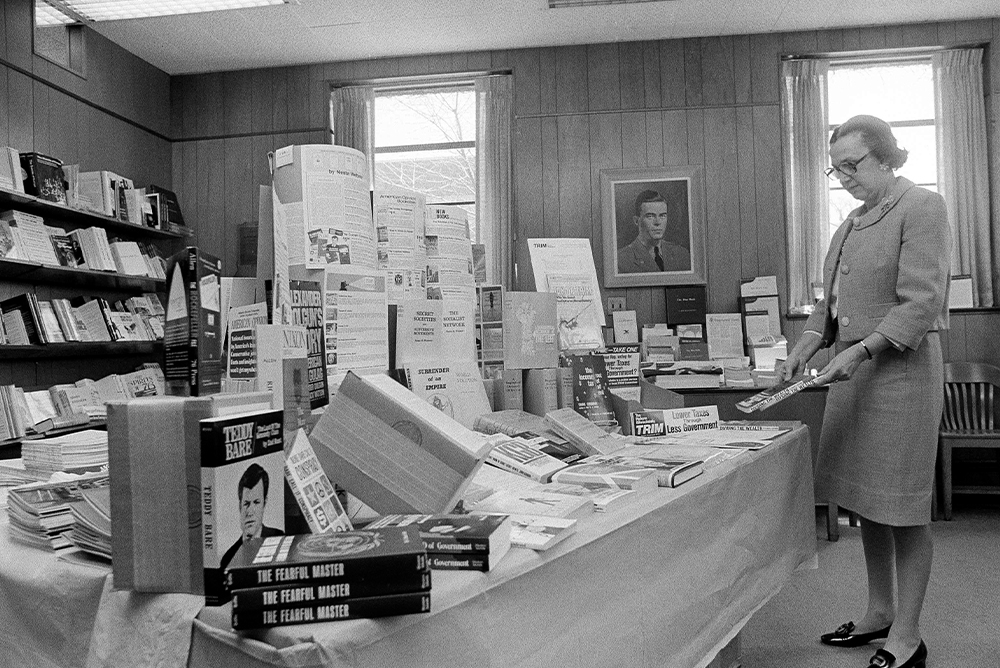

In the 1960s, the John Birch Society sought to impose its version of Christian morality on American public life. Historian Matthew Dallek writes about the grassroots effort that helped defend freedom of expression, pluralism, tolerance, and multiracial democracy back then, and what lessons we can learn from this history today. Courtesy of AP Newsroom.

This May, an email landed in my inbox. The correspondent, who’d come across my new book on the John Birch Society, wanted to share how members of this far-right anticommunist group won control of his local Parent Teacher Association when he was in kindergarten at San Rafael Elementary.

This was early 1960s Pasadena, California, during the rise of the Birchers. What happened then and there was a story unfolding in many communities around the country.

In one way, the story was similar to the pressures that schools are seeing now. In recent years, parents and activists—who, in many cases, are the ideological inheritors of the Birchers—have succeeded in getting large swathes of the country to vet what is taught and read in classrooms, to decide which students can use which bathrooms, and to determine what gender pronouns teachers can use with their students.

But there is at least one profound difference between today and the 1960s: the ferocity of response to such pressure campaigns. While today’s culture warriors often get their way in the schools, the Birchers ultimately failed to capitalize on opportunities like the one in Pasadena.

Why? The counterattacks were too strong. The so-called guardrails protecting democracy were also resilient. When the Birchers made inroads in the media, libraries, and schools more than a half-century ago, they were often stopped, and pushed to the margins. In this Pasadena case, the letter-writer told me, a grassroots effort, which included his mom (who had no apparent history of political activism before this), came together to win back control of their PTA.

His email reminded me how much of the work countering the Birchers occurred out of sight, by parents opposing what they considered an intrusion on their liberties and on their children’s access to a robust progressive education.

It’s this kind of mass mobilization and resistance that’s needed now to defend such ideals as freedom of expression, pluralism, tolerance, and multiracial democracy in America.

The Birch Society was founded in 1958 by 12 white men, mostly Christian and wealthy, including oil and gas magnate Fred Koch, and ex-candy manufacturer Robert Welch, the group’s leader.

But it only exploded into the American consciousness in 1961, when reporters and political leaders revealed to the public that Welch had formed a secret anticommunist society that saw conspiracies proliferating inside the United States. The Birch Society, which numbered between 60,000 and 100,000 members at its height in the mid-1960s, sought to impose its version of Christian morality on American public life. This included giving parents veto power over sex education, giving students easier access to approved pro-“Americanist” texts, and minimizing teachings that they considered antithetical to traditional morality and culture.

In this local work, the Birch Society, while overwhelmingly male in its national leadership, was powered by grassroots efforts by women who used their status as moms to claim a moral order and impose it on schools and communities. Their methods are reminiscent of those used by today’s Moms for Liberty.

Sometimes, the Birchers could win even by losing, inserting their issues into the public square and pushing the conversation in a direction they wished. But more often, the Birchers and their allies lost their fights to take over PTAs and school boards, and to force libraries to stock shelves with conservative tracts. These defeats were fueled by the concerted mobilization of institutions, individuals, and elected officials devoted to repelling the Birch-backed assault on progressive education.

For instance, when Birch leader Laurence Bunker won a seat as a trustee of his local library in Wellesley, Massachusetts, Bunker’s own Unitarian pastor, apparently chafing at a radical’s ascent atop the library’s administration, decided to challenge him in the next election. He ultimately assembled a coalition that unseated Bunker.

In other cases, institutions and their leaders organized the resistance. When Birchers and members of the American Legion in Paradise, California, charged that a popular government teacher Virginia Franklin had immersed her pupils in communist ideas (she exposed them to the Quaker-led American Friends Service Committee), the community largely rallied behind Franklin. Her principal backed her, the school board cleared her of wrongdoing, the media painted her in a sympathetic light, and the courts later awarded her monetary damages in her lawsuit claiming defamation.

The relatively strong popular conviction that progressive education was a cornerstone of shoring up democracy also helped fend off the Birchers. This kind of education was venerated as a bulwark of democracy and individual rights against the ideas of fascism and communism. Progressive education had seemingly helped the United States survive the Great Depression and win World War II by building a corps of citizens who believed in the power of government to do good, felt devoted to their community, and contributed through military, federal, and volunteer service.

Such a broad-minded education was evinced by American philosopher John Dewey, who promoted his ideas in the early 20th century by establishing the Laboratory School in Chicago and publishing Democracy and Education. To imbue students with the values of democratic citizenship, they would be exposed to a range of ideas and perspectives, learn the importance of social equality and an informed citizenship, and explore both America’s greatest triumphs and its abject failures to live up to its ideals.

Though the Birchers never achieved the revolution in public education they hoped for, they did notch a handful of education-related wins. Notably, in 1962, they arguably secured their greatest victory when they helped elect Max Rafferty as California state superintendent of public instruction. Rafferty had drawn Birchers to his candidacy when he delivered a barnburner of a speech to the school board in the Los Angeles suburb of La Cañada, which borders Pasadena.

Titled “The Passing of the Patriot,” Rafferty’s address charged that the public schools were indoctrinating young minds in the poison of communism. The education system, he complained, was churning out a generation of “booted, side-burned, ducktailed, unwashed, leather-jacketed slobs, whose favorite sport is ravaging little girls and stomping polio victims to death.” Rafferty’s broadsides succeeded in getting voters to turn against the ideals of progressive education in favor of a curriculum that favored pro-American tutorials where students would learn to be “militant for freedom” and “happy in their love of country.”

Such a win showed how, using the banner of parental rights, state power could be deployed to enforce a set of norms and values across public institutions. And that same playbook—or at least something that reads like the old Birch playbook—has allowed for the rise of an Orwellian regime of bureaucratic censorship today.

But, as emails like the one sent to me this spring demonstrate, organizing, voting, and activism can counter far-right efforts to control public education at the community level.

Championing the idea of progressive education, in the Dewey tradition, is part of the ongoing work of defending democracy. Disinformation, conspiracy theories, climate change denial, and economic and racial inequalities are rampant in the United States, making progressive education more relevant than ever.

It is needed, as well, to counter the declining trust in the nation’s democratic institutions and reject the growing intolerance toward people of color, LGBTQ rights, and immigrants.

This type of education can also help foster citizens who can tackle the country’s biggest problems. As one scholar put it, Dewey’s vision of a progressive education was to “produce an inquiring student who could change America.”

Though it is harder nowadays to use “sunlight” to expose the excesses of education extremists, it’s still possible to expose the radical nature of the project. If the extremism can be surfaced as an attack on the free exchange of ideas and facts, then some parents might be convinced to enter the fray to thwart the successors to the Birch movement.

Send A Letter To the Editors