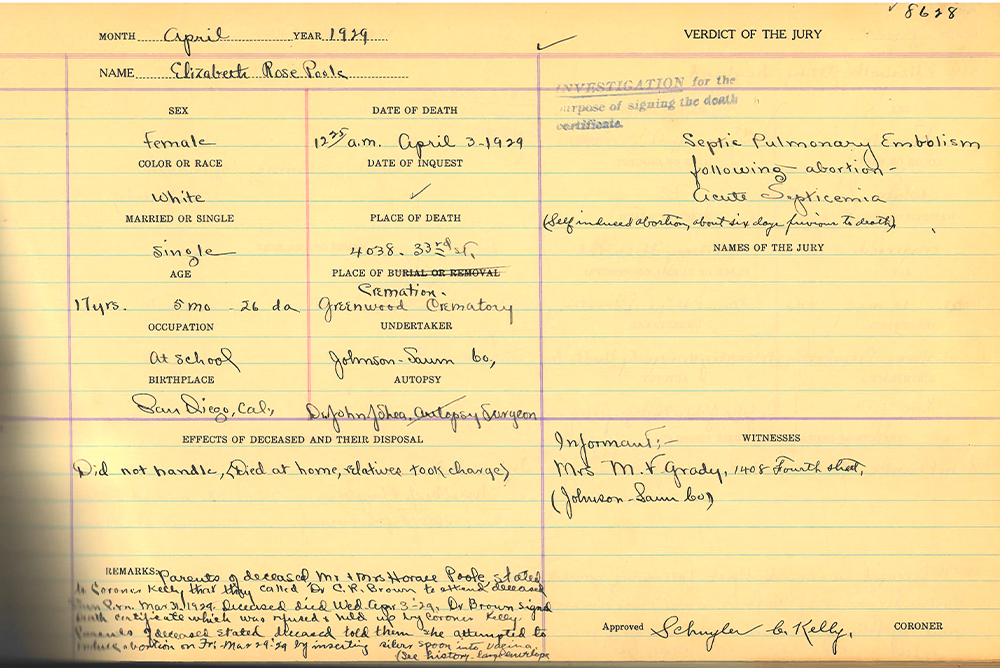

Who decides what stories are worth remembering? Historian Alicia Gutierrez-Romine reflects on why society immortalizes a man’s daring cliff dive, but chooses to forget a woman’s fatal abortion. A scan of Elizabeth Rose Poole’s death record from the San Diego county coroner/medical examiner. Courtesy of author.

In the summers of 1897 and 1898, the San Diego, Pacific Beach, and La Jolla Railroad hired “Professor” Horace Poole to provide Fourth of July weekend entertainment. The spry 20-something doused himself with a flammable liquid and likely took a deep breath before setting himself ablaze, and diving from the top of the La Jolla Cliffs into the sea.

For this miraculous feat, Horace Poole is remembered well in San Diego. Poole Street in La Jolla is a hat tip to him, and his name regularly appears on local history website pages that mention the La Jolla caves.

This essay isn’t about Horace Poole, though. It’s about a lesser-known member of his family whose name only appears briefly, fleetingly, in the annals of history: his daughter, Elizabeth Rose, an early 20th century San Diegan we prefer to forget—even though her story and experiences were far more common than those of her illustrious father.

Young women of Elizabeth’s time are nearly invisible in our history books. They are silent, transient figures in a historical record that obscures about as much as it tells. How should we understand the persistent erasure of women’s history—particularly of centuries of life altering experiences—that society has ignored, forgotten, or dismissed as quotidian and mundane?

On March 29, 1929, Elizabeth Rose Poole, then 17, grabbed a silver spoon and likely took a deep breath before inserting it into her vagina—in hopes of inducing a miscarriage. She became ill, and her condition got progressively worse. On March 31, her parents called on Dr. C.R. Brown to attend to her, but he was unable to do much, and Elizabeth died on April 3, 1929. The coroner listed her cause of death as a “septic pulmonary embolism following abortion” and “acute septicemia.”

We know precious little about Elizabeth. As a teenage girl in 1920s America, she had achieved few of the milestones that would cement a place for her in official records or archives. She hadn’t wed, so there was no marriage certificate. Though her father was at one point well-known, she wasn’t a socialite. There were no mentions of her in the society pages.

Census records help historians understand the people we study, but here, too, Elizabeth Rose eludes. The 1920 Census indicates that the Pooles had six children; only Elizabeth’s younger brother was in school at that time, and while two older siblings worked, Elizabeth (then eight) and two other siblings were unaccounted for. By the 1930 Census, her younger brother and sister (ages 17 and 16, respectively) were both in school, and her older siblings were all working. Elizabeth’s death record in the medical examiner’s office indicates her occupation as “at school,” but I couldn’t find her in any of the San Diego high school yearbooks from the time of her death that I found online.

We will likely never know with whom Elizabeth became pregnant. Was it a boy from the neighborhood or school? Perhaps an older man? Someone she met over the course of her daily routine? A newcomer to town?

Other women who died from illegal or self-induced abortions in San Diego around the same time—like Thelma Jeanne Ferrie, or Gertrude Freedman—share similar blips in the historical record. They’re there, and then they disappear, leaving only slim pieces of evidence (an address, a marriage date) of their brief time on this earth.

Elizabeth didn’t have the “privilege” of being a wife. But being married wouldn’t necessarily have made her pregnancy any less inconvenient. Thelma Jeanne Ferrie, who died after an abortion attempt in San Diego in 1931, was married and had a young son. She sought an abortion after she, her husband, and her mother—who all lived together—realized they could not afford another child in the household.

We know about Horace Poole because a railroad company paid him to jump from a cliff into the ocean a few times—something few of us will do (especially since jumping from the top of the La Jolla caves is now prohibited). His life and memory are preserved because somewhere along the way, someone thought that exceptional act was worthy of remembering.

Last year, when I taught a course on the moral and social aspects of studying history, I posed several questions about this phenomenon to my students: Who decides what history is important? What responsibilities do we have toward the dead? And, do our subjects have the right to be forgotten?

As someone who has extensively researched and written about women who have had and sometimes died from illicit abortions in the first half of the 20th century, I have often pondered on the ethics of what I do: dig through archives to write and tell stories of women’s experiences, stories about which they likely felt shame.

Since women themselves have never wanted to talk much about the procedure—abortion stigma still exists today, even though times have changed—archives reflect medical authorities’ and law enforcement agencies’ investigations, rather than women’s experiences and feelings. Historians such as Leslie Reagan and myself have noted that in the 19th and early 20th centuries, many women had illegal abortions, and they shared information about how to access the procedure through close networks of friends, family, medical providers, and druggists. But word-of-mouth does not produce a historical record as robust as the paperwork produced by professional medical societies or law enforcement.

This paucity of sources raises questions about what we think is worthy of, or important to, remember. When we glorify stories like Horace Poole’s, we commemorate individuals for their exceptionalism. When we deal with widely-shared but controversial experiences such as death and abortion, we sweep stories under the rug. When I tell people I meet that I wrote a book about the history of illegal abortion, they usually respond with raised eyebrows, arms crossed in front of the chest, or some apologia—pro or anti-abortion. They’re uncomfortable. I’m (slightly less) uncomfortable. We move on to another subject.

As much discomfort as these stories may bring, they are worth sharing. Otherwise, we contribute to historical amnesia—a historical amnesia that might lead some Supreme Court justices to opine that “abortion is not deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and tradition”—which simply isn’t true. For centuries, abortion was a pervasive, personal, and painful practice in the United States, and a common, shared experience that the historical record neglected, while elevating the random and seemingly extraordinary feats of otherwise inconsequential men—like Horace Poole’s illuminated dive.

Send A Letter To the Editors