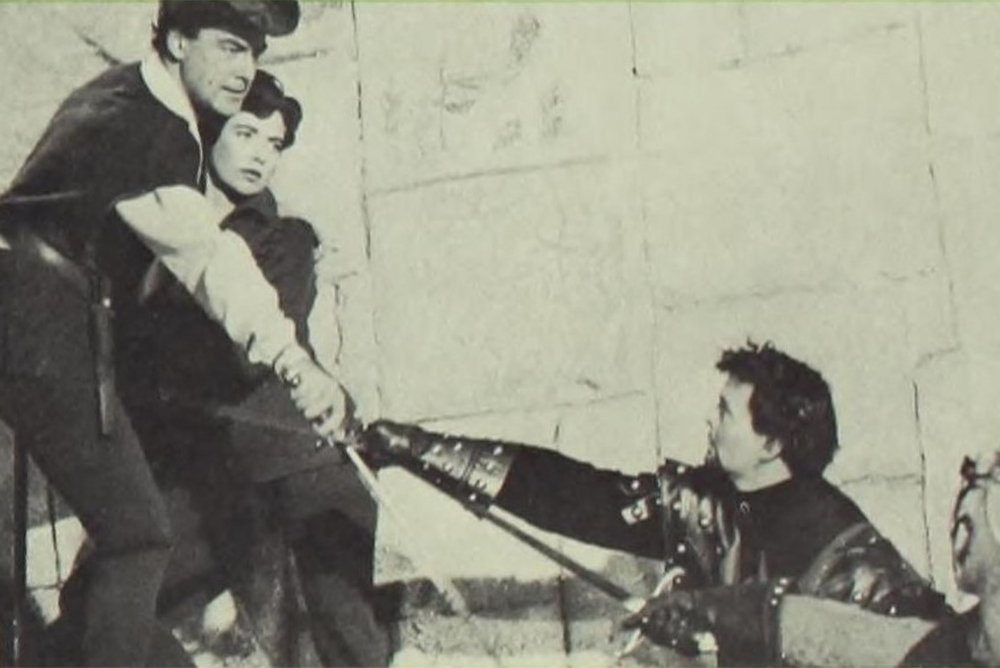

In 1955, blacklisted writers made The Adventures of Robin Hood (above), a hugely popular TV show that resonated with the moment. How did they pull off such a coup? The answer lies with pioneering producer Hannah Dorner Weinstein, historian Julia Bricklin explains. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

In September 1955, 67 TV critics got the opportunity of a lifetime: An all-expenses paid trip to London for a week, courtesy of Johnson & Johnson and Wildroot Cream Oil.

They were there to learn about a new TV program called The Adventures of Robin Hood. The series was the first British-American co-production, and one of the very first programs available in the UK’s then-fledgling commercial television landscape. The half-hour episodes starred Richard Greene as the title character and Bernadette O’Farrell as love interest Maid Marian. It filmed at England’s historic Nettlefold Studios, renamed Walton Studios.

The junket was something out of Mad Men. The critics boarded a martini-and-cigarette-laden charter out of Idlewild Airport, which would later become JFK Airport. They stayed at London’s new Westbury Hotel, and luxury buses shuttled them around to the usual tourist draws, including Nottingham and Sherwood Forest.

Then, there were parties on the actual set at Walton, where the entertainment journalists could mingle with the show’s producers, set designers, actors, and directors.

But not the writers.

The writers of Robin Hood would never be made available for interviews. And they would never be credited for their work on the program, at least not with their own names. Indeed, some of the writers of Robin Hood would not have been allowed to leave the United States.

That’s because they were among Hollywood’s blacklisted—media workers victimized by Sen. Joe McCarthy’s persecution of those accused of communist ties and banned from working.

Had the writers’ identities been discovered, the show couldn’t have proceeded. Johnson & Johnson and Wildroot would have immediately withdrawn their millions of dollars in investment. And this loss of investment would have led to the withdrawal of Official Films, the U.S.-based distribution company that sold the program to CBS-TV in America and the CBC in Canada. Naturally, the broadcasters themselves would have withdrawn their commitment to air it.

So why did the show use these writers despite those risks?

The answer to that question was Hannah Dorner Weinstein.

Weinstein developed the series with leftist writers Ring Lardner Jr., Ian McLellan Hunter, and others. She’d worked with many of them on FDR’s 1944 re-election campaign, as executive director of the Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences and Professions (ICCASP), which she co-founded. They’d also worked together when she was a vice-chair and co-founder of Progressive Citizens of America.

Lardner and Hunter had both been targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), and were unemployable as screenwriters. Their involvement in Robin Hood was known only by Weinstein and two or three others on the show who were sworn to secrecy.

In making Robin Hood, Weinstein followed a formula she developed two years earlier with two other blacklisted writers, Walter Bernstein and Abraham Polonsky. With the writers using pseudonyms, they’d created a single-season detective program called Colonel March of Scotland Yard. That series, featuring actor Boris Karloff (a friend of Weinstein’s), caught the attention of British mogul Lew Grade who decided to help Weinstein build her own studio. She did, and in 1954, Sapphire Films was created.

Still under surveillance by the FBI and the CIA for her own political activities back home in New York, the petite former journalist implemented a strict procedure for getting scripts and notes back and forth across the Atlantic. She did the same with getting the writers paid—no easy feat, considering they had to use pseudonyms for everything. Weinstein, 44 and a single mother of three, sweated mightily each time a journalist asked to speak to one or more of the show’s writers. She’d redirect the questioner to a trusted producer or assistant who would then find a way to deflect.

Weinstein’s choice of the legend of Robin Hood to challenge the cultural climate of the Cold War, and allegorize the contemporary geopolitical conflicts of the period was an apt one. As historian of blacklist-era entertainment Andrew Paul summarizes, Robin Hood “was an outlaw with a keen sense of social justice…His antagonistic attitude toward the authoritarian Prince John and the Sheriff of Nottingham had the potential to reflect midcentury antifascist sentiments. And his empathy toward the poorest of England’s inhabitants could reflect socialist and Popular Front positions on wealth distribution.”

For example, in one episode of the show, called “The Miser,” a lord collects double rents from his tenants to cover his own taxes. Robin tricks him into thinking that an alchemist can turn buttons into silver and returns the money to the villagers. In another episode, “A Year and a Day,” Robin assists a serf who has taught himself how to do surgery by helping the man gain his freedom so he can treat the poor for free.

Lardner and Hunter weren’t the only blacklisted writers involved. Episodes were written by Adrian Scott, John Howard Lawson—members of the Hollywood Ten along with Lardner— and Howard Koch, Waldo Salt, Gertrude Fass, Fred Rinaldo, and Robert Lees (creators of the Abbott & Costello franchise), Arnold Manoff, and Hyman Kraft. Lardner headed up a writing cadre in New York; Scott did the same for Los Angeles.

Weinstein’s productions gave blacklisted writers the ability to put food on their tables, while allowing those same writers to impart sociological subtext about fascism, persecution and, leadership (good and bad). She also allowed them to take aim at the injustices of the Hollywood blacklist.

In “The Vandals,” for example, the sheriff interrogates a village ironsmith to make the man confess that he has made arrow tips for Robin Hood.

“I know you are a decent citizen now,” the lawman goads him, mimicking the language used by Congressional inquisitors who baited former radicals into naming the names of communists and fellow travelers.

Above all, though, Robin Hood was entertaining. The series was a huge hit in the U.S., Britain, and Canada, often taking a spot among the top 20 programs. It was in production for four years and wound up with 143 half-hour episodes. Before its first season was half over, Official Films and sponsors commissioned more seasons of it—and of Sapphire-produced costumed dramas The Adventures of Sir Lancelot and The Buccaneers, featuring a very young Robert Shaw (1956) and then Sword of Freedom (1957).

Ironically, the popularity of these Sapphire programs made life even more difficult for its writers. Talent agents wanted to poach them, but could not find out who they were. The writers couldn’t be at the 1955 junket, and they weren’t ever available stateside, either. The job of deflecting chiefly fell to story editor and trusted lieutenant Albert Ruben, who ran interference between the production company and these types of requests from press or advertising executives.

What made it all work was that Weinstein and her writers trusted each other, perhaps because she faced the same risks that they did. In 1950, she had been fired from her job as a public relations executive for her leftist activity, and her appearance on McCarthy’s list of “concealed communists.” The listing was incorrect—she was not a communist. But, had she not left the country, it was likely she would have been subpoenaed by some arm of McCarthy or the House on Unamerican Activities Committee, or had her passport revoked, or both.

So it was that, in the mid-1950s, this woman who had been outspoken for decades made a shift and let her television productions be the face of her activism. “Meet Hannah [Weinstein],” a British, syndicated columnist wrote in 1959, “the Quiet Woman of television. You won’t have seen her on your screen. She rarely makes news in the papers, avoids interviews if she can. But the fabulously long-running Robin Hood, Sword of Freedom, and Sir Lancelot all owe their tele-creation to this petite American.”

Their writers quietly owed their livelihoods to her, and never forgot.

Send A Letter To the Editors