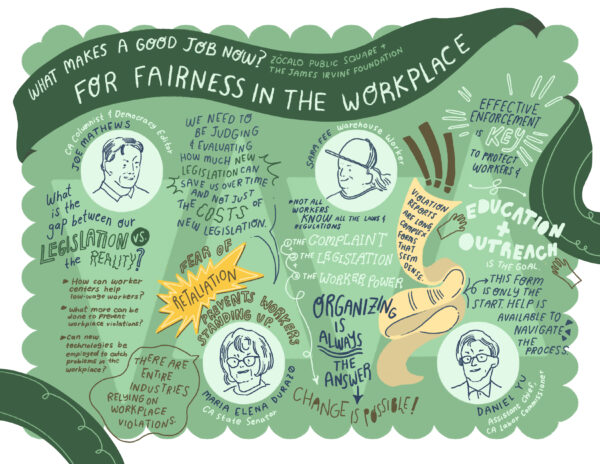

From left to right: Joe Mathews, Maria Elena Durazo, Sara Fee, and Daniel Yu.

California workers’ rights are bolstered by some of the country’s strongest labor legislation, mandating higher minimum wages in many sectors, increased sick days, and other protections. But around the state, “you see quite a bit of suffering” among low-wage workers, Zócalo California columnist and democracy editor Joe Mathews noted Wednesday night.

Mathews was moderating an event on the Capitol steps in Sacramento for the statewide Zócalo Public Square series supported by The James Irvine Foundation, “What Is a Good Job Now?” Many seemingly well-protected workers, he said, deal with wage theft, unpaid overtime, dangerous working conditions, discrimination, and rising employer retaliation.

What has to happen for laws to work on the ground, and why do they fail? The problems are complex, but the solution is usually communication and collaboration, said a panel of three speakers who focus on fairness in the workplace.

Mathews opened the discussion by asking, “What’s the gap between our legislation—our intentions, the policies we put in place—and the realities on the ground?”

Sara Fee, a founding member of Inland Empire Amazon Workers United and a warehouse worker at the Amazon air hub at the San Bernardino International Airport, said, “The gap is enforcement.” Worker power and organizing can help close that gap, and laws give organizers a place to start—but laws are difficult for workers themselves to enforce. For one thing, it’s not clear where complaints should go; human resources, she noted, works to limit company liability. Fee was lucky enough, she said, to have the help of the nonprofit Warehouse Worker Resource Center when she took action against Amazon.

California Labor Commissioner assistant chief Daniel Yu said that there are not enough investigators to cover every single violation in California, so his office focuses on making “each enforcement action more than the specific action itself.” For example, recovering wages for one group of workers gets them the money they are owed while simultaneously putting the employer—and other employers in the same sector—on notice, and offering worker education and outreach.

Mathews asked California State Senator Maria Elena Durazo if the state government is having conversations about the need to allocate more funds to enforcement.

Durazo said that unfortunately, budget conversations are typically one-sided: Lawmakers discuss how much something is going to cost, but “we don’t talk about how it’s going to save us from having to provide food or rental vouchers or all those other things” that the government pays for.

Bringing the discussion back to the ground level, Mathews asked where workers who feel they are being treated unfairly can start—what kind of complaint do you file, where do you go, and how do you get educated?

Yu, who acknowledged his answer might seem self-serving, recommended the California Labor Commissioner’s Office. The first step does involve filling out a very long form, he said, but added that he and his colleagues can also help by phone and redirect workers as needed to other government agencies.

Fee said that if she’d seen the form alone, she would probably have said, “Forget it.” But she had the help of a worker center, which does education and outreach at workplaces—including finding out if violations are taking place—and connects workers and enforcement agencies. Ultimately, the center helped build a bridge between workers and government, and helped her learn about her rights and stand up for them.

“Organizing is always the answer. Worker power is always the answer,” said Fee. “When you have people who have your back in your workplace, you can change things, and I know that you can because we’ve done it.”

Durazo added that it’s not a complicated form that keeps people from standing up for their rights but rather the fear of retaliation, job loss, or worse. “Entire industries rely on violations of workplace rights” to operate, she said. And employees in those industries “know that when they assert their rights they’re going to be fired and/or risk deportation, and/or risk other things.”

Mathews asked what more can be done to prevent these violations—could agencies utilize technology, like surveillance or algorithms that predict problems, rather than waiting for the problems to come to them.

“I won’t reveal all of our trade secrets in this conversation,” said Yu. But “we don’t abide by a strict complaint-based model. We are increasingly trying to be proactive.”

Durazo added that the state budget has included funding—which began during rampant COVID lockdown-era labor violations—for worker centers and on-the-ground organizations to do more outreach to help workers connect and build collective strength.

Fee said that putting these many pieces together is changing lives and making workplaces safer. “It’s a little bit slower than a worker on the ground would like it to be,” she said, and wages still aren’t high enough—but she is seeing effective cooperation among government agencies, workers, and organizations.

Yu offered one example of a “highly effective” partnership that led to a significant enforcement action. A janitorial subcontractor that supplied workers for various Cheesecake Factory locations was paying workers below minimum wage, making them work unpaid overtime, and not giving them enough breaks. Yu’s office typically would have gone after the subcontractor, but that business couldn’t afford the backpay, so the office also found the Cheesecake Factory liable. Such actions have a ripple effect. Subcontractors around the state began letting clients know they were following the law“This was impactful not only for the workers, but for the industry as well,” said Yu, adding that some employers have thanked the Labor Commissioner’s Office, “which is rare.”

Before turning to audience questions, Mathews asked the panelists for actionable advice—what are red flags to look for in a new employer, and what do you do when things start to go south?

Yu said getting paid late or not having an accurate pay stub are big red flags, and advised workers to start documenting patterns of violations or abuses.

Fee said to beware, after your honeymoon phase at any new job, if early promises—about future opportunities or a higher salary—seem false. And as soon as possible, organize.

The question-and-answer session came from the livestream audience, who dove into specifics of the panelists’ experiences.

The first question was for Yu: Is there a sector of the California economy that sees the most workplace complaints?

Yu said there are several industries, and named just a few: restaurants, agriculture, warehouse, garment, janitorial, residential care facilities, and construction.

Next up was Fee. What has been the hardest part of your organizing experience?

The retaliation, she said, including getting put “in unfavorable positions.” Retaliation “affects your mental health when you’re not allowed to express yourself or speak to other people in your workplace.” Ultimately, however, standing up is worth it, she emphasized.

Send A Letter To the Editors