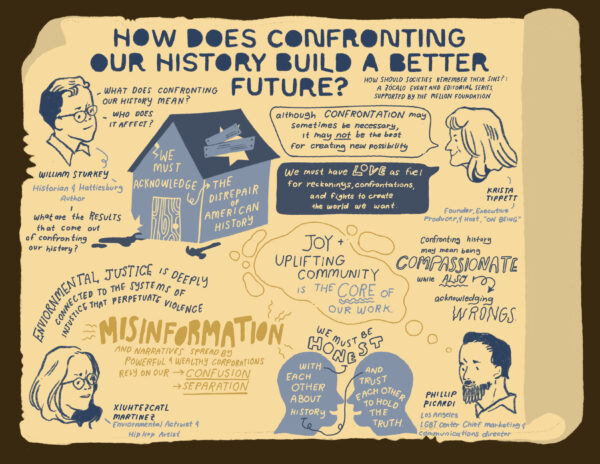

From left to right: William Sturkey, Xiuhtezcatl Martinez (Xochimilco), Phillip Picardi, and Krista Tippett.

Confronting America’s history is like fixing or maintaining an old home: acknowledging the parts that are in disrepair, and those that are rotten to the core. This is the metaphor historian William Sturkey opened the fourth and final program in the Zócalo/Mellon Foundation series “How Should Societies Remember Their Sins?,” and in which the panelists found themselves building upon throughout the night.

“How Does Confronting Our History Build a Better Future?” featured environmental activist and hip-hop artist Xiuhtezcatl Martinez (Xochimilco), L.A. LGBT Center communications officer and former editor-in-chief of Out magazine Phillip Picardi, and “On Being” founder, executive producer, and host Krista Tippett.

To open the conversation, Sturkey, the moderator, turned to Tippett: What does it mean when confronting our history also means confronting other people in this society?

Tippett shared that through her work she tries to shine a light on spaces where confrontation isn’t necessarily the key, instead focusing on building “hospitable spaces.” She acknowleged that there are limits to the types of spaces she aims to create, but she still sees value in the work of fostering “quiet encounters and relationships away from the glare of the hyperreactive society and so-called discourse that we have.” Later in the night, she added: “Confrontation is a necessary word, and a necessary act. But it’s not necessarily very pragmatic.”

Next, Sturkey asked Picardi to explain what confronting history looked like to him. Picardi described a moment when he was editorial director at Teen Vogue, in the wake of Nancy Reagan’s death in 2018. As other outlets were publishing laudatory coverage of the late public figure, Picardi and his team decided to run a piece titled “Former First Lady Nancy Reagan Watched Thousands of LGBTQ People Die of AIDS” to reckon with her legacy during the HIV/AIDS crisis. “I understand that the critique was that it may have felt disrespectful of the recent passing of this woman, and I do hold space and compassion for that,” Picardi said, “while also holding a deep-seated rage for the people who died in shame, who were people who I could have built connections with and who could have been proud forebearers of queer tradition that never got to live out the full potential of their lives.” He added: “If we’re not going to be honest with each other about the history, I think we’re just doomed to repeat the sins of our past.”

What, Sturkey asked the panelists, are the most important results that come out of confronting our history that will help us build that better future?

Martinez said that Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission—taken in concert with more recent government raids and arrests of Indigenous people opposing the construction of pipelines through their land—is demonstrative of why reconciliation alone isn’t always enough. Instead, Martinez offered the Land Back movement as an example of effective change that can return power and resources to Indigenous peoples. Later, he added that the movement was already steeped in a sense of forgiveness, one of the core tenets of reconciliation: Land Back has nothing to do with revenge or “enacting the same violence that we suffered,” he said. “Land Back for many of us encompasses a liberated future for all of us.”

Picardi commented on the hard task of asking the most impacted people to do the heaviest lifting to enact societal change. “We’re often asking folks who bear the brunt of society’s ills to hold the grace,” he said. “People are fed up right now with having to be graceful.”

Tippett encouraged those that are not the “most vulnerable to being wounded” to step up to do this essential work. She reflected on the ways in which a stubborn refusal to fully reckon with our history has left us haunted and fractured. America, Tippett said, has a way of believing that we’re always getting better. Instead of facing the centuries of atrocities, like lynching—which happened “town by town, tree by tree”—we avoid internalizing hard truths. What we stand to gain, then, in confronting history is “wholeness,” a future of “whole human beings in a whole society.”

Sturkey pointed out that two of the three panelists (Tippett and Picardi) earned a master’s degree in divinity. It’s often said that religious texts point to a “usable past” of redemption and restoration. What do you think about the role of religion in historical confrontations?

While Tippett said she doesn’t look to religious institutions or “the loud voices who stand up to represent everyone else,” she does see some benefit in turning to the vocabulary of religion. “I care about these traditions as the place in the human enterprise across time and space where we have language and practices and rituals like confession and repentance and lamentation and redemption.”

Reflecting on religion, both Martinez and Picardi drew on their personal histories and confliction with the Catholic Church. Martinez: “My understanding of Catholicism is as the primary tool to dehumanize and justify the genocide of my ancestors, and the stealing of our lands, the erasure of our language.” Still, Martinez said he aspired to learn and understand how to reach beyond that violent history to “create reparative conversations.”

Picardi, a gay, ex-Catholic, said he reframed and reclaimed his relationship to the Church after attending divinity school. Now, working at the L.A. LGBT Center has shown him new ways to understand his faith and the work it calls people to do. “If you want to see god, go see a social worker,” he said.

The night ended with a special performance by musicians from the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, a Black musical ensemble founded in Los Angeles in 1961. But before the reception, Tippett urged the audience and her fellow panelists to take a moment to reflect on the transformative nature of the very moment they all found themselves in. For Tippett, the very stage that had been set that night was unimaginable to her in the past—“this configuration of humanity, this subject, these questions.”

“Even just 10 minutes after we sat down up here tonight,” she said, “I was listening to the three of you and looking at you and thinking of what we were discussing and how we were discussing,” she said. “When we have these moments of seeing the generative narrative unfolding, the fuller telling of truth, the fuller living into truth—let’s take that in.”

Send A Letter To the Editors