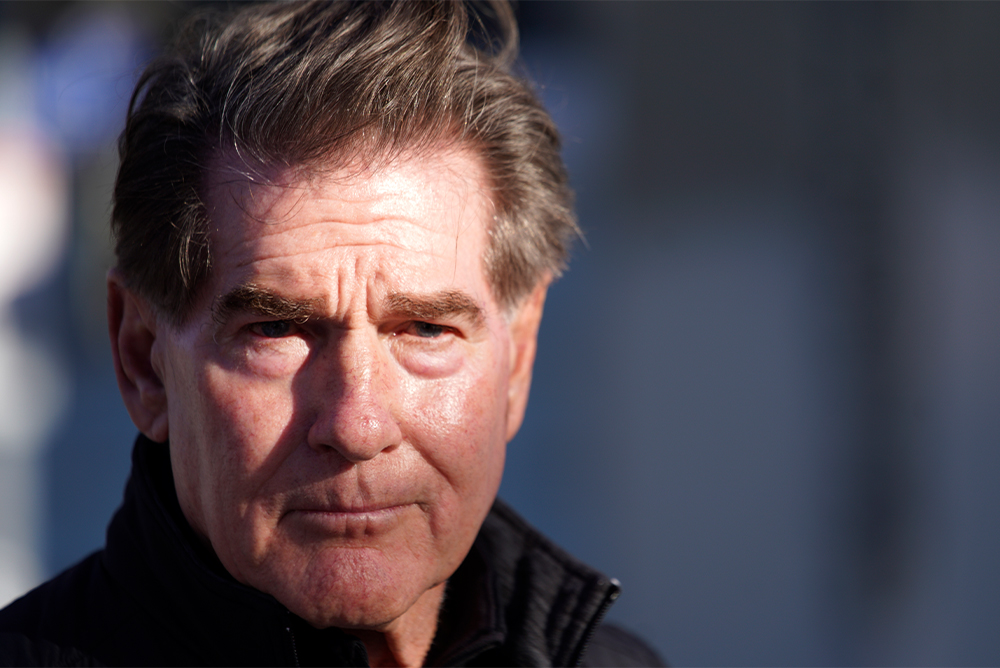

“In baseball, as in politics, success is often a matter of positioning,” writes columnist Joe Mathews, reflecting on former-Dodger-turned-Republican-candidate Steve Garvey’s bid for California’s U.S. Senate seat. Courtesy of AP Newsroom.

Many of us aren’t old enough to remember it, but Steve Garvey, now the leading Republican candidate for California’s U.S. Senate seat, started his career on the left.

The left side of the infield, that is. When the Los Angeles Dodgers first called up Garvey to the majors at the end of the 1969 season, he played third base.

Soon, however, Garvey on the left became a defensive disaster. He had a powerful arm, but he was dangerously inaccurate. He so often threw balls over the first baseman’s head and into the stands that fans began bringing gloves—not to catch a souvenir, but to defend themselves.

In 1973, the Dodgers moved Garvey to first base, where he only had to catch the ball (first basemen rarely throw). With his defensive liabilities hidden, he could focus on his excellent hitting. He’s stayed on the right side ever since.

In baseball, as in politics, success is often a matter of positioning. You may fail in one spot, but flourish in another where your weaknesses are less apparent.

That’s also the strategic thinking behind Garvey’s current campaign for Senate. At 75, the former first baseman is a first-time political candidate for a powerful office. He has little record of public service, and a post-baseball record with some ugly errors.

But he may well be in the right position. He’s the only Republican with a recognizable name running for U.S. Senate in the March election, which is enabling him to consolidate support on the right side. He also has the good fortune to be running in California’s peculiar top-two election system—which makes our state’s politics a lot like baseball, and less like democracy.

Baseball is often described as a team sport, just like American politics, which is a contest between Democrats and Republicans. But in reality, baseball is an individual sport: The sport’s fiercest battles are between individuals—the pitcher vs. the hitter—and within teams, as teammates compete against each other for positions and playing time.

California’s top-two system makes party politics more like this—it sets up clashes between individual politicians who are members of the same team, usually the dominant Democratic Party. Currently, three ambitious Democratic members of the House of Representatives—Adam Schiff, Katie Porter, and Barbara Lee—are fighting each other for the U.S. Senate seat, and dividing up votes.

Garvey is using that dynamic to his advantage. With his consolidated GOP support, he has a good chance of winning the most votes in the March primary. At the very least, he is all but certain to be one of the top two candidates in the returns, allowing him to advance to the November election against one of the three Democrats.

Garvey, a Republican who has said he voted twice for Donald Trump, would be a heavy underdog in November against any Democrat. But simply getting Garvey to November would be a huge victory for the Republican Party, in California and nationally.

In previous elections, when two Democrats advanced in the U.S. Senate races, the GOP saw drops in turnout among its voters, hurting Republican candidates for seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. But with the well-known Garvey on the ballot, more Republicans would show up, which would, in turn, boost the Republican congressional candidates in House races.

That’s significant because the results in several California swing districts could determine which party controls the House of Representatives.

Garvey’s ability to draw votes may depend on how well he can hide his weaknesses. He has kept an unusually low profile so far, and up until the first televised debate of the campaign last night, he’s avoided media scrutiny that could bring up many embarrassing moments from his past.

At the end of Garvey’s playing days in the late 1980s—he retired from the San Diego Padres after spending most of his career with the Dodgers—he went through a public divorce; his first wife, Cyndy, wrote a tell-all book that tarnished his ‘Mr. Clean” image.

Also in this period, two different ex-lovers filed paternity suits, revealing Garvey had fathered two children out of wedlock. The scandal inspired a famous bumper sticker on disappointed fans’ cars, across Southern California: “Steve Garvey is Not My Padre.”

Since then, Garvey’s notices have not been much better. Early in the 2000s, the Federal Trade Commission pursued penalties against him, alleging he made more than $1 million through “flagrantly false and deceptive claims on behalf of a weight-loss program in infomercials.”

In 2006, the Los Angeles Times reported that Garvey and his second wife, Candace, were living extravagantly while dodging debts—bouncing checks (including at a grocery store), and failing to pay phone and electric bills. Garvey stiffed his gardener, his pediatrician, his nanny, and his church. One attorney to whom he owed money told the Times: “Once a Dodger, always a dodger.”

At the time, Garvey acknowledged financial problems, but blasted his creditors for attacking him in the press.

Memories of those reports have faded. As a candidate, Garvey hasn’t really explained these problems or how he overcame them. His web site portrays him merely as a successful businessman and philanthropist.

He hasn’t said much to the press about much of anything else. He’s done few public events, and offered little detail on his policies or what he might do for California in the Senate.

Garvey’s campaign visuals and videos are mostly about his baseball career. They emphasize the days when he helped lead Dodgers and Padres to the World Series. His interactions with voters, too, are often about his glory days at first base.

After all these years, he’s still hiding his weaknesses over on the right side of the field.

Send A Letter To the Editors