With party conventions and a presidential election coming up this year, former Clinton staffer Ben Austin reflects on volatile times at the 2000 Democratic National Convention in downtown Los Angeles. Activists demonstrating outside the Staples Center. Courtesy of AP Newsroom.

In 2000, I ended up in a cage outside the Democratic National Convention (DNC) in downtown Los Angeles wearing a dark suit, swimming against the current in a sea of pierced protesters, raging against Rage Against the Machine.

As a kid who grew up in Dogtown and Z-Boys’ Venice, back when shops on Abbot Kinney sold cheap crack instead of artisan coffee, I had spent plenty of time raging against the machine. My punk rock youth took place in an alcoholic home, with a father who committed suicide, in a Venice patrolled by gangs. I knew who “The Machine” was, and it certainly wasn’t me. But there I was, in my suit, having quit a job at a fancy law firm to become the communications director for the 2000 DNC host committee, trying to control an uncontrollable demonstration. I was playing the part of “The Man” right out of central casting.

At the time, I lived in a strip of Marina del Rey called the Marina Peninsula that L.A. Times columnist Patt Morrison once labeled the “Clinton Ghetto” because so many of my fellow Clinton White House expats lived there: Rica Rodman, Jon Orszag, Rod O’Connor, Chad Griffin, and Rick Miller, to name just a few.

The Democratic National Convention was organized by the Republican Mayor of Los Angeles Dick Riordan—for whom I’d later serve as deputy mayor—and led by his top aide Noelia Rodriguez. Riordan’s close ally, civic leader Eli Broad, was bankrolling the convention just as he was stepping into his now-iconic role as a literal and figurative architect of modern Los Angeles. Simultaneously, the 2000 Republican National Convention in Philadelphia was being hosted by a Democratic mayor—across-the-aisle collaboration that feels like a quaint anachronism today.

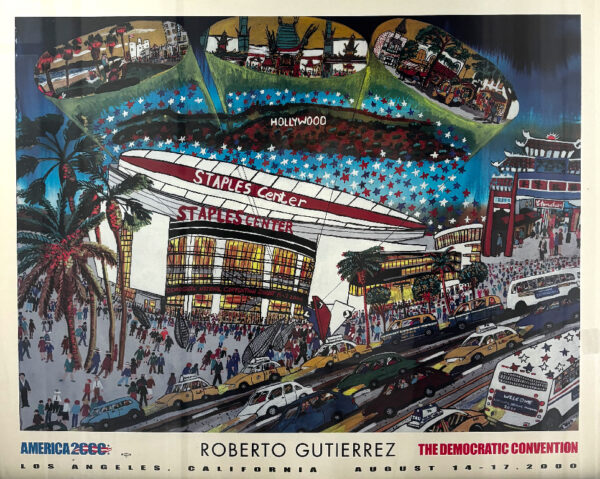

Part of what drew the DNC to Los Angeles was the brand-new Staples Center, which two decades later, already marks a bygone era. In 2021, Staples Center was renamed the Crypto.com Arena—just a year before Sam Bankman-Fried’s infamous fall from grace that would ironically re-anoint staples as a smarter 21st-century investment than crypto. Two months before the DNC, the Staples Center hosted the first Lakers world championship since the Showtime era. As a fanatical lifelong Lakers fan, I took full advantage of my temporary, DNC-related all-access to watch the series-clinching championship game standing directly behind the basket. At one point, Shaq’s giant hand engulfed mine in a high-five, and I even walked into the locker room after the game to brazenly steal one of Kobe’s towels (which I still have).

When convention week finally began and the political world descended upon Los Angeles, Democratic consultant Paul Begala’s famous quote about politics came to mind: “Washington is Hollywood for ugly people.” For one fleeting week, the ugly people took over Tinseltown and got to be the movie stars.

I spent much of that week interacting with reporters in a time before the internet rendered them an endangered species. The center of gravity in the media universe for convention week was the L.A. Times, the cultural and political chronicler of Los Angeles, with great journalists like Jim Newton, Matea Gold, Michael Finnegan, Jim Rainey, Duke Helfand, Beth Shuster, Mark Barabak, Bill Boyarsky, Steve Lopez, Patt Morrison, and Janet Clayton.

This was all happening against the backdrop of a city finally emerging from a deep recession and civil unrest in the wake of the Rodney King beating. The convention slogan labeled Los Angeles “the capital city of the 21st century.” With the new millennium, we were ushering in a new downtown, a new economy, and a new identity. This same pre-millennium optimism had also infused the party’s national narrative. My old boss Bill Clinton famously framed his administration as “the bridge to the 21st century.”

Now, six conventions later, a series of budget cuts—including this month’s draconian layoffs—have hollowed out the L.A. Times newsroom just when democracy needs journalism the most. And the capital city of the 21st century has transitioned from an era of civic giants like Tom Bradley, Dick Riordan, Eli Broad, and Antonio Villaraigosa into an era of casual corruption. It seems like every other council member is in jail, is under investigation, has been indicted, is overtly racist, chills cash bribes in their freezer, or is for sale at the bargain price of a USC professorship or a lap dance.

A few months after the DNC, the Florida recount would shake American democracy. Less than a year later, 9/11 would upend our collective sense of security and redefine U.S. foreign policy. Two decades later, January 6, 2021, would usher in an unimaginably darker descent into tribalism, authoritarianism, and national division.

But inside the convention hall on August 17, 2000, the biggest scandal was Al Gore’s slobbery kiss of his then-wife Tipper on stage before his acceptance speech. And the biggest concern amongst political operatives like myself was bartering the green “middle-school-geek” credential into a “political-nerd-cool-kids-club” orange floor pass by the end of the day.

Three nights before that speech, Rage Against the Machine performed a concert in a designated protest zone outside the convention hall. The show would be a harbinger of the darker times ahead—at least for those who were paying attention.

I left in the middle of the concert to hear President Clinton’s speech from the convention floor (brandishing my successfully acquired cool-kid orange credential), after lead singer Zack de la Rocha defiantly declared that “our democracy has been hijacked.”

By whom, I thought?

Soon after I left, the concert devolved into violence between the protesters and the Los Angeles Police Department, which was still embodying the macho cowboy culture left over from Chief Daryl Gates. The title of Rage Against the Machine’s new album, The Battle of Los Angeles, was all the excuse they needed to break out their fancy riot gear.

Rubber bullets, tear gas, and chaos engulfed downtown Los Angeles that night, while I instead listened to President Clinton tout an airbrushed version of 1990s “peace and prosperity” from within the sheltered confines of the convention hall. I was proud to have played what I felt like was my very small part in that peace and prosperity: to have done everything from working on his presidential campaigns and in his White House as a young (unimportant) staffer to flying around the world on Air Force One representing the United States.

But I had a hard time relating to the existential split-screen inside and outside the convention hall. I couldn’t understand why the protesters were so angry, and I didn’t immediately appreciate the Orwellian irony of journalists getting shot at inside what we’d labeled the “First Amendment zone.”

As we approach the 2024 nominating conventions and presidential election and I reflect on that moment in time, I can see now how that night represented a liminal state for our local and national narratives—a transition from a troubled past into an imagined future that never materialized. The stark contrast inside and outside the convention hall that night signified those narrative threads coming apart at the seams.

Seven years later, I saw Rage Against the Machine perform again in a diametrically different Southern California setting: Coachella. As I took in the bucolic scene, it occurred to me that they might have known more about the trajectory of our city and our nation than I gave them credit for at the time.

Maybe I was The Machine. Maybe I had left something behind in my youth, in other epochs, and maybe it would do me good—however difficult the task—to sort through it all: the man, the machine, and all that rages in between.

In retrospect, maybe we also shouldn’t have been in such a hurry to usher in the 21st Century.

Send A Letter To the Editors