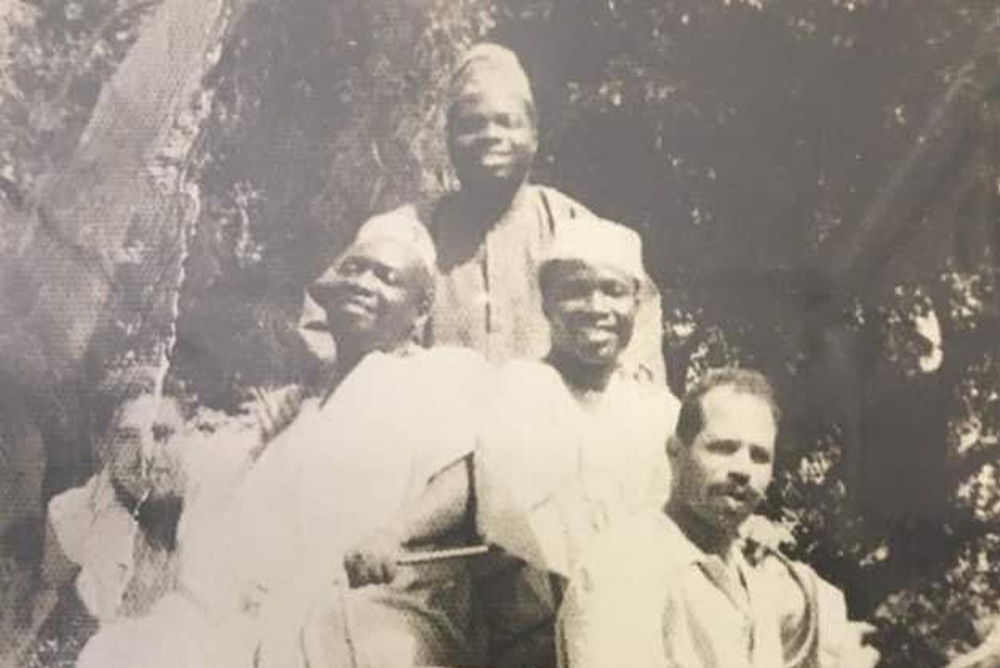

Writer Ahmad Adedimeji Amobi reflects on his father, second from left, who spent his life promoting Arabic and Islamic learning in Nigeria. Courtesy of author.

On a phone call the other day with a new friend, Zay, we ended up on the topic of religion. “Did you attend madrasah?” I asked her, referring to the Arabic schools that offer primary and secondary education where subjects like the linguistic characteristics of Arabic and Islamic theology and jurisprudence are taught.

She responded yes, but that she no longer remembers most of the things she was taught there. “I can still write my name in Arabic, I can still write Bismillahir Rahmanir Raheem, and oh, yeah, I can still write some of the 99 names of Allah,” Zay said.

Zay’s experience is reflective of people of my generation in the southwestern part of Nigeria, where I’m from. Most only attended madrasah when they were young, before dumping it when they emerged more fully into life. Some, like Zay, told me they ran away from madrasah because their teachers, or ustadhs, flogged them too fiercely. But others told me that they dropped out to focus on their Western education, which they knew was the more economically sound path.

For me, balancing these two schools of knowledge has always seemed normal and natural. Growing up, I attended Western school Monday through Friday and attended madrasah on Saturdays and Sundays. The reason my experience was different was thanks to my father, who spent his life promoting Arabic and Islamic learning in Nigeria. The more I’ve learned about his efforts, the more I’ve realized why it meant so much for him to encourage Nigerians to be proud to speak Arabic, and study at madrasah, rather than let this education fall by the wayside in a country where there is little profitable motivation to pursue it.

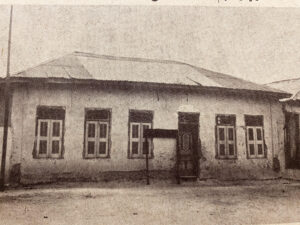

In the 1960s, the author’s father established the Arabic studies school at the family house in Iwo. Courtesy of author.

Growing up, I knew, even as much as my mother tried to conceal it from me, that my father had died when I was still in her stomach. As I got older, I started to ask for more information. When I was 10, she pointed at an old landscape photo that hung above the window of our living room. In the picture, my father, a Black, plump man, is standing amid Arab men, smiling. Later, when I was 15, I came across an undated, self-published book my father wrote, titled “The Presence of Arabic Language and the Religion of Islam in Southwest Nigeria.” In the introduction, he observed that Christian missionaries were “snatching the children of Muslims into their English schools in order to get them to abandon their religion and take up their religion or believe in any other religion.”

To understand what he meant by this, it’s important to understand the history of Islam and Christianity in Nigeria. Both are understood to be colonialist ideologies because Nigeria, before it became Nigeria, had its own traditions. But both belief systems have permeated Nigeria thoroughly (today approximately 51% of the country identifies as Muslim and 47% identifies as Christians).

My father was likely writing in the 1950s, at a time when more students began to leave Arabic schools for English schools. The Christian missionaries, my father posited, were able to sell them on a Western education because it promised them more opportunities for advancement. Arabic studies, at the time, only promised to teach a better understanding of how to worship God—seemingly at odds with a growing and modernizing economy. He recognized that if something didn’t change, it would put the study of Arabic and Islam on a path of gradual erasure in the Nigerian educational system. So, he thought: Let me establish something similar in Arabic so as to attract back the Muslim children.

In the 1960s, he began this work, establishing his own Arabic school, which originally started at the family house in Iwo, before it took on a modern classroom-based learning setting in 1962. He called the school, which I later attended, Markaz Shabaab–l–Islam, or the Islamic Youth Center. Other scholars in the region, like Sheikh Adam Al-Ilory, created similar educational programs to build standards and structure around Arabic studies at the time.

Despite their work, the present structure of the Nigerian education system offers fewer and fewer opportunities for advancement for those who attend madrasah. That’s why, though the number of Arabic students produced every year in its junior schools equals, if not exceeds, the number of students produced in Western schools, the drop-off point that follows for secondary school is steep. Unlike madrasah, Western schooling offers students an opportunity to dream of, for instance, attaining government or white-collar jobs. When students finish madrasah, there should be something equivalent in the system which guarantees them an application to higher institutions, for instance, without sitting for external examinations, to incentivize further Arabic study.

I think about what it would look like if Nigeria valued Arabic education more and rewarded the efforts of those who are still passionate about learning the language. It is not about Islam, the religion, but Arabic itself, because faith is different from knowledge, just as a Western education is different from Christianity. The way I see it, for the Arabic language to have permeated our culture so thoroughly since its introduction in the 11th century through the northern part of the country, disseminating through trade and migration with North African countries like Egypt and Sudan, makes it even more deserving of study. This is especially the case in a complicated region like the southwest, where our Indigenous language—Yoruba—does not share similar phonemes with Arabic.

Though my father’s struggle was a long time ago, his determination inspires me today; he started his Arabic studies at a young age, learning the rudiments of the Qur’an from his paternal grandfather, Sheikh Bukhari. To learn modern Arabic, he traveled to different Arabic-speaking countries. His first trip, to Saudi Arabia in 1942, came at a time when such a trip necessitated taking camels and horses. When such transportation was not possible, he trekked on foot. What made it worth the struggle? I think the answer is that faith and a thirst for knowledge can be chronic.

Before I read my father’s book, I was unconsciously starting to throw myself wholly into Western education, because that’s understood to be the path to thrive in the country. But his writing has helped me recognize how important it is to not throw away his work, and this legacy of being a student of two schools of knowledge.

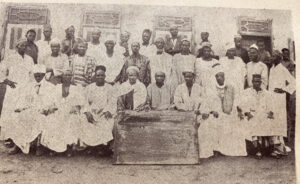

The final pages of my father’s book include three photographs. The first is a group picture of my father and his first set of students at the Islamic Youth Center. Tiny in the picture, he looks way younger than the photo my mother first showed me of him. The second picture is of him, flanked by older men, robed in Agbada, embroidered, traditional Yoruba attire. All of them wear caps and firmly-knotted turbans. The caption under this picture reads, “a picture taken by friends and well-wishers as send-off for Al-Hadj Ahmad Muhaly Al-Bukhary on his trip to Mecca and some Arab countries.” The third picture is an isolated picture of the first building in the school my father established. A wooden signpost rests against the wall of the building, the door and the windows shut. The caption below the picture reads, “Here is the picture of Islamic Youth Center in Iwo.”

Staring at these pictures, I wonder if my father knew that all his hard work would make a difference. But the more I look, the more I am certain he knew that the school he built would. It was his way of ensuring that he could share his wisdom and teachings with generations to come—offering inspiration to me and others who continue to matriculate through that door captured in the photograph.

Send A Letter To the Editors