The public square is the meeting ground where people make society happen. In these spaces, physical or metaphorical or digital, we work through our shared dramas and map our collective hopes. Ideally, the public square provides room to solve the problems we face. It is also where new, thorny issues often arise.

This “Up for Discussion” is part of Zócalo’s editorial and events series spotlighting the ideas, places, and questions that have shaped the public square Zócalo has created over the past 20 years.

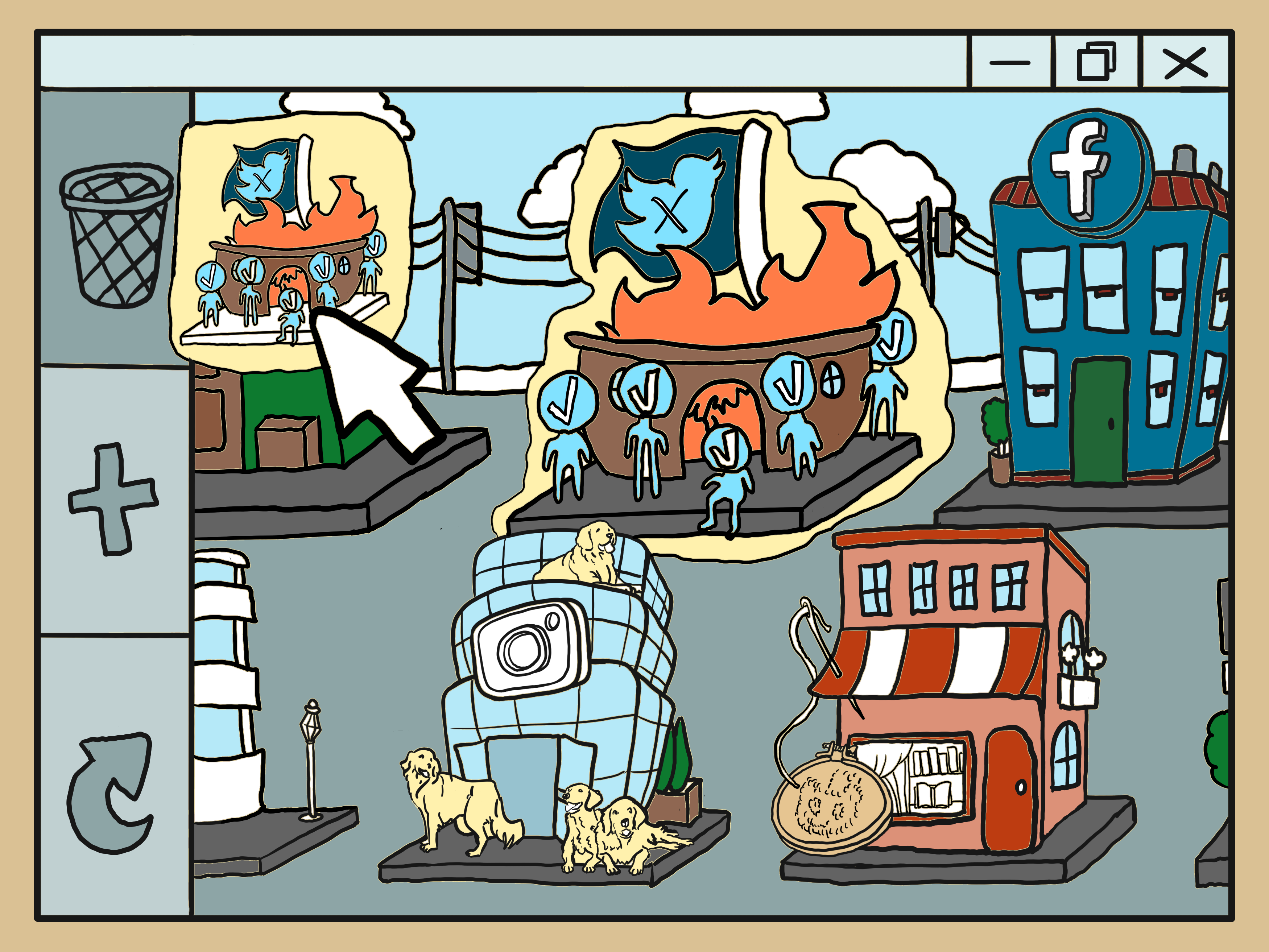

Here, our contributors take on the virtual worlds where we connect, from internet discussion boards to “the fediverse.” These very online writers are scrolling the puppies of Instagram, building governance structures to regulate digital discourse, and breaking the spells cast by technological magic.

They were the perfect people to answer the question: What is the future of the digital public square?

The past few years have been dark ones for the digital public square.

Elon Musk has transformed Twitter (now X), a space much used, if not always loved, by activists and diverse voices, into a far-right echo chamber where only those willing to pay reach audiences. Reddit, long a platform of choice for communities hosting conversations about “Call of Duty” or crochet, declared war on its own users last summer, ousting moderators who protested changes the company made, and limiting the tools users can use to access and edit the site. Lawsuits and court cases, as well as changes platforms have made to their software, have made the task of researching online communities harder. Scholars warn that we are ill-prepared to monitor mis- and disinformation online in the run-up to the 2024 U.S. presidential election.

If there is a silver lining to these storm clouds, it is that millions of users are discovering better ways to interact online. Over 100 million users joined Threads in its first week of operation, a new social network from Meta, whose main selling point seems to be “it’s not Twitter.” Smaller bands of dissidents have joined Mastodon, an open-source Twitter alternative where each server can have its own rules of the road, while some Reddit communities are migrating to Discord channels, choosing to hold conversations under their own rules rather than under Reddit’s management.

Users are choosing spaces where they can decide what speech is allowed and what is banned, taking control of moderating these online spaces from the big corporations and bringing it back to communities.

In 2000, the political scientist Robert Putnam warned that Americans were allowing our civic fabric to unravel by isolating ourselves and withdrawing from local institutions like the bowling league and community groups. Social media has countered one of Putnam’s concerns—the loss of “weak ties,” connections between people who know each other but not necessarily well. (My wife and I are college friends who reconnected on Facebook—thank you, weak ties.)

But Putnam’s warning that we have been losing the practical training in democratic practices that we got from the Elks club or the PTA seems worth addressing. As people take responsibility for governing and moderating their online spaces, perhaps this can become a new training ground for engaged citizenship.

Ethan Zuckerman is professor of public policy, information, and communication at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and director of the Initiative for Digital Public Infrastructure.

There is no single digital public square. My Reddit, X (Twitter), Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky—each is completely different from yours, and each is distinct from the other. In that way, we each have several of our own public squares, like owning—or, perhaps more accurately, renting—homes in several different states, each with its own set of rules and norms.

As custodians, we each create spaces where we can invite over our friends, though sometimes we have to deal with intruders or neighbors we might not have chosen.

My Reddit and Instagram presences reflect the fair amount of time I’ve spent cultivating them. These public squares give me what I want. On Reddit, I see discussions about cross stitch (the only craft I can handle), journalism, literature, movies, reality TV, the gig economy. The subs I follow are well moderated, with rules that keep out or at least minimize those who are misogynistic and racist (we all know they find their way to even the most pleasant of spaces). I indulge my gossipy side with “Am I the Asshole,” where I waste far too much time; I peek in on Reddit throughout the day. I only check into Instagram—about 70% golden retrievers and 30% friends’ kids—a couple of times a week.

But there are limits to the idea that you can make the public square you seek. If, god forbid, I were to post something on Reddit that made it to the front page, I’m sure I would be confronted with a barrage of harassment. My Twitter used to be quite pleasant, as Twitter goes (or went), but changes Elon Musk has made have bulldozed the public square I made for myself. Every day I seem to be placed on at least three spam bots’ “Hi” lists. No longer do replies appear in a way that prioritizes the people I chose to follow—now those folks’ thoughts are buried where I can’t find them. They are beneath the blue checkmarks I have no interest in, purchased by people whom I’m suspicious of at best.

That means, to make these digital public squares work for me, I have to be willing to give up when I can’t keep a level of control. I don’t want to spend time in a place that doesn’t offer me intriguing discussion mixed with joy and pop culture recommendations (I like my morning scroll to include the latest discourse on Vanderpump Rules). Because the ultimate power I have over my social media spaces is to decide where I want to be.

Torie Bosch is the opinion editor at STAT and the editor of You Are Not Expected to Understand This: How 26 Lines of Code Changed the World.

Two crucial features of the 21st-century digital square receive less attention than well-known attributes like its lack of gatekeepers, the importance of algorithms, the presence (or lack) of echo chambers and filter bubbles, and the tantalizing possibility of virality.

First, today’s digital public square is enormous. Second, it is optimized for search. This means that each of us is only going to be familiar with an infinitesimally tiny piece of it: the piece we want to see. We search for content directly, or algorithms and curating networks serve up information we’re apt to like.

Our siloed digital lives therefore can make it hard for us to have a broad conversation about what the digital public square is, or what it should be. The problem here is that the piece of the digital square that I see (say, a supportive community that shares my interests and hobbies) might be very different than the piece of the digital square you see (maybe: political arguments).

That’s where the kind of research we do at NYU Center for Social Media and Politics comes in. We analyze large quantities of data that can help us better understand what is actually happening in the digital public square writ large. Anyone can find an example of anything on a social media platform, but studying things like trends over time, content proportions, and actual exposure to information on social media platforms requires more than just finding cases of something. For example, we analyzed over 1.2 billion tweets to get a large-scale picture of hate speech on Twitter over the course of the 2016 election campaigns. Without this kind of at-scale understanding of what is happening online, it is hard to even agree on what problems need to be solved, let alone what the solutions might be.

The catch is that we need access to data to do this kind of research—and that access remains completely at the whims of the platforms. This begs important questions. Does the public only want to know what is happening in the digital square when the platforms decide to let us? Or do we need to turn to legislation and regulation to make sure society knows what is actually happening in its digital square.

Only once we know what is really happening in the digital public square can we begin to figure out whether it is, or is not, working for us.

Joshua Tucker is professor of politics and co-director of the Center for Social Media and Politics at New York University.

In many places around the world, the digital public square is just a fiction. Internet shutdowns are on the rise, with governments restricting access to websites they perceive as a threat, or shutting down internet services altogether in specific regions or around elections. There were 187 documented government-backed internet shutdowns in 2022. Meanwhile, journalists, advocates, and ordinary citizens are subject to increasingly pervasive digital surveillance. For example, the notorious Pegasus software was used to spy on the communications of at least 189 journalists, 85 human rights defenders, as well as judges, lawyers, and union leaders in 20 countries such as India, Hungary, and Morocco from 2016 to 2021.

In the face of such digital repression, the U.S. and other democracies must advance a rights-respecting, democratic vision for governing technology. There’s low-hanging fruit: in the U.S., Congress has yet to pass a comprehensive law to protect people’s online privacy, or to stop law enforcement from ignoring warrant requirements and simply buying data about suspects from commercial data brokers who track internet users’ every move. Too many people still lack access to affordable, high-quality internet service. And in the deluge of content that floods online sites daily (including mis- and disinformation and, increasingly, fake content created through generative AI), governments must figure out how to support authoritative information on issues ranging from elections to public health without starting a political food fight.

A free, democratic digital public sphere requires two elements: first, the ability to express ourselves, access information, and find community online; and second, the ability to do so privately, without fear of government surveillance or profiling by companies. Our digital world is complex—but there are steps lawmakers can take now to boost these essential features of the digital public sphere.

Alexandra Reeve Givens is the CEO of the Center for Democracy & Technology, a nonpartisan nonprofit focused on protecting civil rights and civil liberties in the digital age.

We live in an era of magic. There is technological magic—the quasi-spiritual power we ascribe to things like AI, self-driving cars, and space travel. Then there is traditional magic—witness the surge of interest in astrology, divination, and herbalism, as people try to make sense of this rapidly changing world.

Magical practices have long served society, giving us a sense of our place in a big, chaotic world and reminding us of our interconnectedness, and our bonds with other living creatures and the earth. The implicit assumption of astrology, after all, is the idea that we share a common humanity shaped by the stars and the rotation of the earth.

Our sense of awe for technology dates from at least the Industrial Revolution, with the rise of what philosopher Leo Marx called the technological sublime — that magical feeling we attach to technology for its potential to reshape our lives. As Sabine LeBel has written, this “elevates technology with an almost religious fervor, while simultaneously overlooking some of the consequences of industrialism.”

This flavor of magic posits that more and better technology will always advance human progress. It is also likely to shape the future of the digital public square, as LLMs, sorting and selection algorithms, image recognition, and other technologies operating under the banner of artificial intelligence shape the interactions we have in online spaces.

But this limits what we think possible. What if our digital public square moved beyond magic as technical wizardry and incorporated the magics of interconnectedness, social responsibility, and care? What if our visions of the future set aside technology as the primary solution and brought forth social and community infrastructures designed around the needs of the most marginalized?

There are many practical steps forward. Imagine, for instance, the sort of digital public infrastructure proposed by scholar Ethan Zuckerman, which takes lessons from public broadcasting. Or consider the promise of the fediverse, which enables more control of our social spaces, provided you have the technical capacity and skill to implement and manage them. Legal frameworks like Europe’s GDPR, Brazil’s LGPD and California’s Delete Act are worth studying—for both their benefits and limitations for future legal thinking.

But to move forward more effectively in digital society, we first need better visions of the future that inspire us to a stronger, more magical society that’s human first and then digital.

AX Mina is an artist and culture writer exploring contemporary spirituality and technology. She co-produces Five and Nine, a podcast about magic, work, and economic justice.