From left to right: Khalil Kinsey, Maurice Harris, aja monet, and Jacques McClendon.

On the rarified second level of SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, California, amid premium owner suites and premium beer sales, there’s an Angela Davis quote plastered on a wall.

“Our histories never unfold in isolation,” reads the excerpt from the scholar and activist’s 2015 book, Freedom Is a Constant Struggle. “We cannot truly tell what we consider to be our own histories without knowing the other stories. And often we discover that those other stories are actually our own stories.”

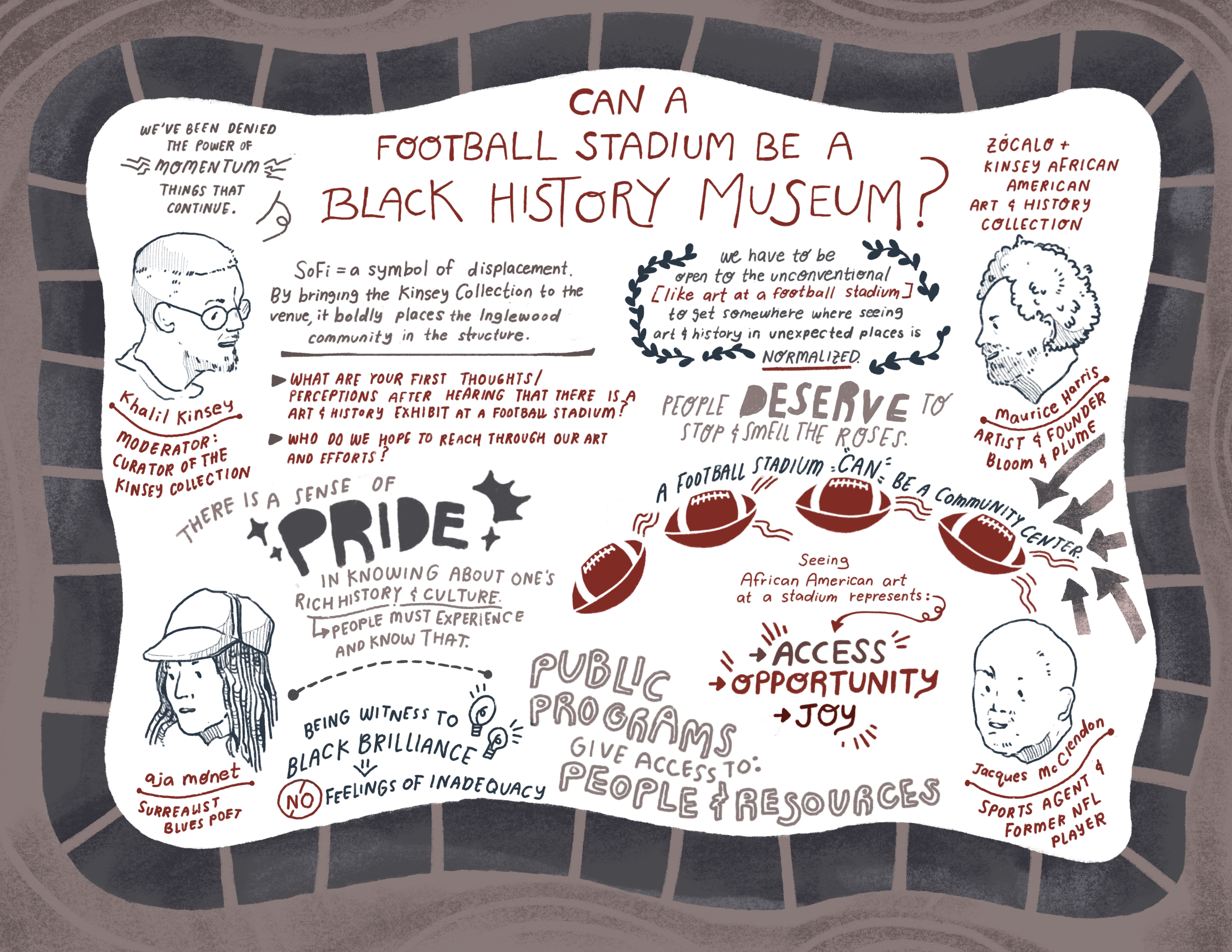

The quote is part of a temporary exhibition by the Kinsey Collection, one of the world’s largest private troves of African American art and history, which has taken up residence at the sports and entertainment venue. It was the inspiration for Zócalo’s public program there last night, which asked: Can a football stadium be a Black history museum? The conversation was presented in partnership with the Kinsey African American Art & History Collection at SoFi Stadium and California Humanities.

At first, the panel, made up of a poet, an artist, a former football player, and the chief curator of the Kinsey Collection, prevaricated around the framing question.

It’s certainly random, Maurice Harris, the founder of floral design studio and coffee shop Bloom & Plume, finally said. But soon the panelists leaned in. During the conversation, they made a case for why it matters to bring history—especially history that’s all too often left out of textbooks—to spaces like this, in order to meet people where they are and make these stories as accessible as possible.

The program began with a poetry reading by panelist aja monet. Before reciting “An ode to Black skin,” monet commented on an original Phillis Wheatley collection of poetry hanging on display nearby. For those who might not know, Wheatley, she explained, was the first published African American woman poet, who wrote at a time when it was illegal for enslaved people to read or write in the U.S. “What a treat we all get to witness this in a stadium,” she said.

Khalil Kinsey, the moderator, started off the discussion then by explaining why he and his family brought Wheatley, alongside other known Black luminaries and names that have been lost to history, to SoFi Stadium.

Kinsey said that he and historian Larry Earl, who co-curated the show, first thought about the people of Inglewood. Since SoFi opened its doors in 2020, many locals have seen the towering, futuristic venue (which remains the most expensive stadium in the world) as a symbol not of uplift but of displacement and erasure, ushering in a wave of gentrification that promises to transform the area.

We wanted to reflect communities here, and place them “boldly” in this structure, said Kinsey.

The two curators also thought about football itself.

An estimated 70% of NFL players today are Black, but it was only three years ago that the NFL ended “race-norming” in dementia testing, a practice rooted in eugenics, which assumed that Black players started out with lower cognitive function than white players. Currently, the league is facing multiple racial discrimination lawsuits.

By putting Black stories in a football stadium, Kinsey said, he and Earl hoped that the exhibition could be a “small part of lending a broader view of humanity for the athletes on the field.” This is an experiment for both SoFi and the Kinsey Collection, he added. “But we were eager to see its effectiveness because we’re terribly interested in improvement.”

Kinsey asked the panelists to share their reactions to the exhibition.

“When I see African American art in a stadium, what it means for me is access, opportunity, joy,” said Jacques McClendon, a sports agent and former NFL player. “Football has an immense platform and immense responsibility,” he added. And, having spent a career in football stadiums, he knows that these venues can be more than a place for sports. “They can be community centers,” McClendon said, gesturing around the room at people in the audience.

monet said that it took her a moment to wrap her head around what she might add to the conversation—“A poet in a football stadium?” she joked. But then, she said, she started to think about how poets can help people find the layers and dimensions in the world around them. “Poets can see a forest in a tree, or a museum in a stadium,” she said.

Noting the pervasiveness of white history on structures, institutions, streets, in the U.S., she said, “it’s on us to try and be committed to broaden and expand and include what makes America ‘America,’ and what makes Black people a part of that story.”

Harris spoke about how he sees the exhibition at SoFi in parallel with his own work, running a bespoke floral design studio and a coffee shop.

There are a lot of hurdles in getting people to go to a museum, he noted. “If you can find a way to show folks something they weren’t expecting in a place they were already going, I think that’s really moving the needle and pushing the conversation forward.”

That’s why he opened a coffee shop, he said. It offers him a means of sharing his arrangements in a more public space to make beauty more accessible. “For so long, especially as folks of color, we’ve just been in survival mode. We don’t have time to make it pretty. We should have time to do nothing for a second. To smell the roses.”

That’s something that artists can help with, monet agreed. “How can we democratize art so people understand they are the artists of their own lives? Imagine what beauty we could create—the things that could be possible.”

In-person audience members and those on the live YouTube chat had a chance to ask the panelists questions at the end of the discussion.

One person wanted to know what the future of the Kinsey Collection might be, since it departs SoFi next week.

We’re beginning conversations about how to give it a permanent location in Los Angeles, said Kinsey.

The final question of the night asked how people can do more to capture and amplify local stories here in Inglewood.

Kinsey spoke about the power of momentum. “I think that we’ve been denied the power of momentum. Things that continue. And that as a result of continuing, they build, they grow, they speed up, they accelerate.” But this can only happen, he said, if you’re consistent and moving forward. “I’d encourage you to just start. You’ll be surprised at the signs that appear along your path just by keeping your head down and staying focused on that mission.”

People stayed late after the discussion for a reception with KCRW DJ Novena Carmel that gave audience members the chance to eat, drink, talk, and dance together. Many also took the opportunity to get one last look at the traveling exhibition, named the “Myth of Absence.”

“When this closes: white walls,” Kinsey said, touching on the collection’s departure during the discussion. “It’s going to feel different. And the people who have been here will always notice that.”

Send A Letter To the Editors