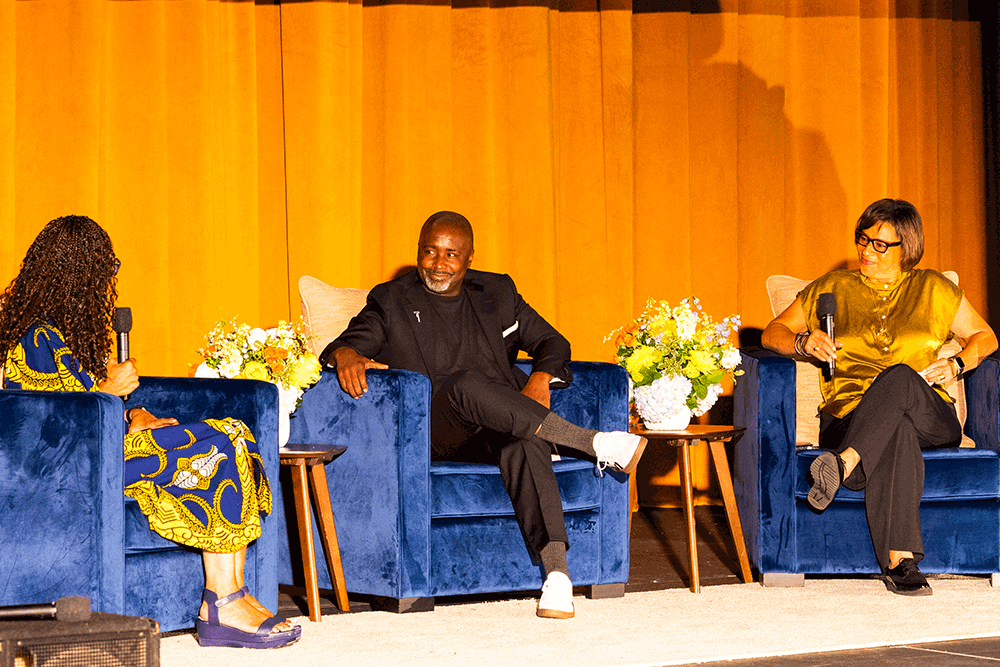

From left to right: Destination Crenshaw senior art advisor V. Joy Simmons, Los Angeles City Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson, and architect Gabrielle Bullock.

“We are the hub of a community,” asserted Crenshaw High School principal Donald Moorer, who opened Thursday’s Zócalo event. It was the first in a series partnering with Destination Crenshaw, the organization behind the 1.3-mile-long public art and infrastructure project being erected along Crenshaw Boulevard.

The event was an invitation for panelists and audience members to consider the community stakes of the ambitious project—which includes pocket parks and original artworks by Alison Saar, Maren Hassinger, and Kehinde Wiley—and what it means for Black history, Black art, and Black success.

The event’s title, “How Do You Grow a Rose From Concrete?,” was inspired by the famous Tupac Shakur poem, “The Rose That Grew From Concrete.” And as the project’s concrete is still being laid, some of the visionaries behind it took the stage at Crenshaw High: architect Gabrielle Bullock, Los Angeles City Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson, and Destination Crenshaw senior art advisor V. Joy Simmons.

They took turns asking one another questions, co-moderating the event—a format that held true to the sense of co-creation, collaboration, community, and contribution that all of them hope Destination Crenshaw will instill in each person who finds themselves in its midst.

Simmons asked the councilmember, a “son of South Los Angeles” whose mother was one the first people to graduate from Crenshaw High, what the Crenshaw Corridor was like when he was growing up. “The thing I remember most,” he said, “was that there was always motion.” Whether it was cars bouncing on hydraulics, young people doing the latest dance moves, entrepreneurs sweeping in front of their storefronts, or churchgoers coming and going, Crenshaw is “where life happens, where we witness what others are doing.”

When Crenshaw got wind that L.A. Metro was expanding a new train line and potentially cutting through their neighborhood—without stopping—Harris-Dawson was part of early efforts to win a Leimert Park station.

“This train could be a knockout punch” for the neighborhood, he said, transforming real estate, safety, and its connection to the rest of the city. For Harris-Dawson and others, one aim was undeniable: “We set out to do a project that would make us permanent in the City of Los Angeles. So no matter what happens going forward, there’s not going to be a situation where you get to say we were never here.”

That spirit of visibility—to be seen for what Crenshaw is—is one of the main reasons the train will be overground. In those earlier days, at the same time that Crenshaw community members were fighting for the train to be underground, Beverly Hills was fighting for it to stay above. Harris-Dawson asked why, and learned that they wanted to display what they had to offer: their shops, businesses, restaurants, museums, landscapes. Crenshaw could do that, too.

Drawing on an understanding that people will oppose what you do to them and embrace what you do with them, Harris-Dawson got community buy-in from businesses, neighbors, and leaders along the way. In fact, the construction site was able to get over 70% of its workforce from local hires, Destination Crenshaw president and COO Jason Foster noted later.

“I want the people of South Los Angeles to feel like it’s theirs,” Harris-Dawson said, just as other Los Angeles areas like Boyle Heights and Chinatown feel a sense of ownership over their neighborhoods. He also hoped that because consumers of Black culture would have to come to Crenshaw to experience this cultural project, the neighborhood could prosper.

“This project for me is a gift,” said Bullock, who co-led the design for Destination Crenshaw. Like Harris-Dawson’s efforts, the architecture firm Perkins&Will gave the people of Crenshaw power in design voice, she said. “In the end, we are merely interpreters.”

Bullock has been involved with other large-scale projects that highlight Black America: the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.; the National Center of Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, Georgia; and Emancipation Park in Houston, Texas.

How does Destination Crenshaw compare? Simmons asked.

Because the project’s origin is in the community and will represent them, Bullock said, it is unique.

At one of the first “visioning workshops,” where community members were encouraged to bring an artifact or object that meant something to them related to Crenshaw, LA Commons founder and community leader Karen Mack brought in an image of the Sankofa bird, whose turning head is meant to symbolize the need to look to the past in order to move forward.

Hence, Sankofa Park will be the largest gathering area at Destination Crenshaw. The park itself has elements shaped like the bird, and on its highest viewing deck, you are able to look back and see where you’ve come from. “It’s about storytelling,” Bullock said.

The story Destination Crenshaw tells was important to Simmons, too. As the art and exhibition advisor, she selected artists who told a generational story of Crenshaw—ranging from in their 20s to 96 years old. There will be a sculpture on car culture by Charles Dickson (who will join the second event in this series, on May 31). And the RTN Crew will once again adorn the Crenshaw Wall with a new incarnation of mural art. Simmons noted that since at least the 1970s, the retaining wall has captured traces of the community through art, serving as a sort of public canvas. “I wanted us to understand that we are not a monolith,” she said of her selections.

All the panelists shared what they hope people will feel and take away from this project: that people feel seen, feel the intentional work put into it, and go away with a sense of the excellence of Black Los Angeles.

Many members of the in-person audience had deep roots in Crenshaw, which was made clear during the Q&A period that followed the talk. One questioner was the daughter of a former principal of Crenshaw High, another was a community historian.

One audience member asked where the late Crenshaw rapper Nipsey Hussle was in all of this. The name Destination Crenshaw, in fact, was inspired by Hussle, who thought it should be called that to mark the historic Los Angeles community as such: a destination, in bloom.

Send A Letter To the Editors