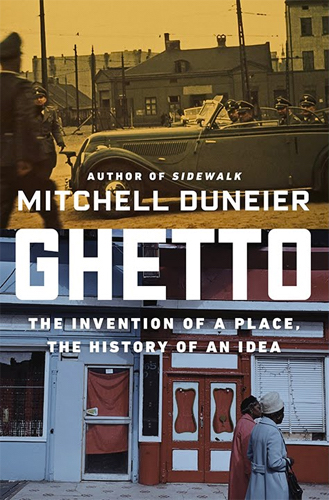

On March 29, 1516, the city council of Venice, Italy issued a decree forcing Jews to live in il ghetto—a closed quarter named for the copper foundry that once occupied the area. The term stuck, and 500 years later the ghetto—both the term and the reality to which it refers—is still with us. How did the ghetto go from being a word associated mainly with the segregation of European Jews to a concept used to describe the lives of poor blacks in U.S. cities? How is it that centuries after Napoleon emancipated the Jews from their ghettos, Americans still perpetuate residential exclusion? And why, despite the heavy social costs that come with segregation, aren’t Americans any better at countering the impulse to ghetto-ize? Princeton University sociologist Mitchell Duneier, winner of the seventh annual Zócalo Book Prize for Ghetto: The Invention of a Place, the History of an Idea, visits Zócalo to examine why the ghetto endures.

The Takeaway

Mitchell Duneier Explains the Invention of the Ghetto, as Place and as Idea

The Zócalo Book Prize Winner Discusses the Evolution of Ethnic Enclaves, from Renaissance Europe to the Modern U.S.

When sociologist Mitchell Duneier was growing up in the 1960s, he said, “references to the word ghetto were references in my house and in my segregated Jewish community on Long …