You would never know it from their denunciations of “Obamacare,” but in the battle over the 2010 healthcare law, conservatives have been fighting against ideas they once approved–and still approve in other contexts.

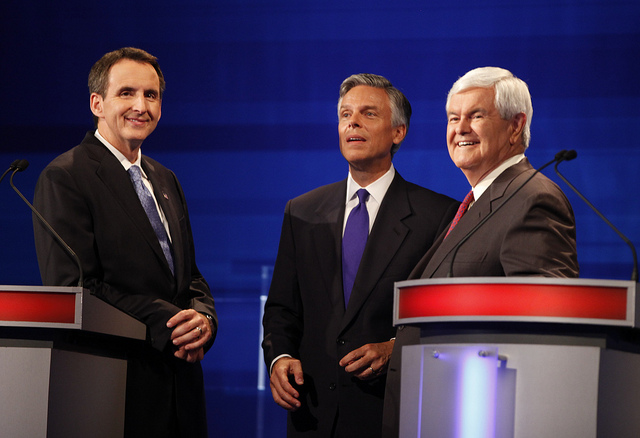

The 2010 legislation calls for the establishment of insurance exchanges, subsidies to the poor and near poor to make insurance affordable, and a mandate requiring individuals to maintain a minimum level of health coverage. That approach was championed originally by the leading conservative think tank, the Heritage Foundation. It was the basis of legislation co-sponsored by 20 Senate Republicans in the early 1990s, and it was the framework of the reforms that Mitt Romney enacted when he was governor of Massachusetts. Romney isn’t the only Republican presidential candidate haunted by his record on the issue; his main rival, Newt Gingrich, also used to support an individual mandate, though he has now apologized for it.

Moreover, the framework of the 2010 Democratic reforms bears a striking resemblance to current Republican proposals to convert Medicare into a “premium support” system. Under those proposals, Medicare would remain compulsory; Americans would have no choice about paying taxes for the program during their working years. Then, when they became eligible for Medicare–whether at age 65, as under current law, or at age 67, as under the budget introduced by Rep. Paul Ryan and approved by House Republicans–they would receive a “premium support” (more generally called a voucher) to cover part of the cost of enrolling in a private insurance plan.

Moreover, the framework of the 2010 Democratic reforms bears a striking resemblance to current Republican proposals to convert Medicare into a “premium support” system. Under those proposals, Medicare would remain compulsory; Americans would have no choice about paying taxes for the program during their working years. Then, when they became eligible for Medicare–whether at age 65, as under current law, or at age 67, as under the budget introduced by Rep. Paul Ryan and approved by House Republicans–they would receive a “premium support” (more generally called a voucher) to cover part of the cost of enrolling in a private insurance plan.

Democrats object to Ryan’s proposed elimination of the traditional, public Medicare program and his plan to tie the value of the voucher to the consumer price index, which has long grown more slowly than medical costs. These provisions would dramatically shift healthcare costs to the elderly. But the Republican plan for Medicare does resemble the 2010 Democratic legislation in its basic “architecture”: health insurance exchanges, affordability subsidies, and an individual mandate.

Medicare is not the only area where Republicans would like to introduce changes that resemble the 2010 healthcare law. GOP proposals for privatizing Social Security follow a similar pattern. Under those proposals, Social Security would remain a compulsory program; workers would have no choice about whether to pay into it. But they would be able to choose among a set of private-investment alternatives (and the value of the annuities they received would vary with the success of their investment choices). In other words, there would be an individual mandate for retirement savings, but the vehicles for these savings would become private.

So while conservatives now object to the individual health insurance mandate and other provisions of the 2010 law, it’s not clear that this is an objection on principle. The rule seems to be that a mandate for private insurance is acceptable when they propose it, but when Democrats do, it is an intolerable violation of individual liberty.

As so often happens in the United States, a debate about whether a policy is legitimate has become a debate about whether it is constitutional. This coming spring, the Supreme Court will hear arguments about the constitutionality of the individual mandate. If the law had been drafted differently, it could have provided a clear constitutional rationale under the taxing power of Congress–the same rationale that Social Security and Medicare have. For example, the law could have imposed a healthcare tax and then provided an off-setting credit to all those with private insurance; the net result would have been the same as the mandate. But Democrats shied away even from the use of the word “tax” and instead justified the mandate under their authority to regulate interstate commerce. That choice has left the law vulnerable to challenge.

But should thoughtful conservatives want to see the mandate overturned? After all, a decision against the mandate could have wider implications, undermining the legitimacy of other proposals conservatives favor.

That concern was raised in a fascinating opinion on the individual mandate by Judge Brett Kavanaugh, a conservative, Republican appointee to the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals. The D.C. Circuit is one of the appellate courts that ruled in favor of the constitutionality of the mandate. Judge Laurence Silberman, appointed to the bench by Ronald Reagan, wrote the majority opinion, a striking affirmation of the mandate’s constitutionality.

But just as striking was the dissent by Judge Kavanaugh, a figure who bears watching.

Some observers have suggested that although we don’t yet know who will win the Republican presidential nomination, we do know the identity of the next Republican nominee for the Supreme Court–Brett Kavanaugh.

To the disappointment of some conservatives, however, Judge Kavanaugh did not vote to strike down the mandate. Nor did he vote to uphold it. He ruled instead that under the 1867 Anti-Injunction Act, no one has standing to contest the mandate until penalties are imposed under the law–that is, not until 2015. But by then, he noted, the law might be revised (or possibly repealed), so the courts would never have to resolve the issue at all.

Toward the end of his opinion, Kavanaugh introduced another reason–a “results-oriented” consideration–for judicial restraint on the mandate:

This case also counsels restraint because we may be on the leading edge of a shift in how the Federal Government goes about furnishing a social safety net for those who are old, poor, sick, or disabled and need help. The theory of the individual mandate in this law is that private entities will do better than government in providing certain social insurance and that mandates will work better than traditional regulatory taxes in prompting people to set aside money now to help pay for the assistance they might need later. Privatized social services combined with mandatory-purchase requirements of the kind employed in the individual mandate provision of the Affordable Care Act might become a blueprint used by the Federal Government over the next generation to partially privatize the social safety net and government assistance programs and move, at least to some degree, away from the tax-and-government-benefit model that is common now. Courts naturally should be very careful before interfering with the elected Branches’ determination to update how the National Government provides such assistance.

The only surprise about this point is that it took so long for a conservative to make it. The individual mandate is the child of conservative thought. Killing that child might be satisfying for immediate political reasons, but it would make no sense from the standpoint of conservatives’ long-term goals. In thinking about what the Supreme Court will do, conservatives might heed an old caution: watch what you wish for.

Paul Starr, a professor of sociology and public affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton, is co-editor of The American Prospect magazine and author of Remedy and Reaction: The Peculiar American Struggle over Health Care Reform.

Buy Remedy and Reaction: Amazon, Skylight, Powell’s

*Photo courtesy of IowaPolitics.com.

Send A Letter To the Editors