Witty Mosaics Offer a Beautiful Solution to the Pothole Problem

One Artist Is on a Quest to Improve City Streets via a Durable Ancient Craft

Back in 2013, Jim Bachor had the idea of bringing art to bear on a particularly non-artsy problem—potholes.

Outside his Chicago studio, the pavement was marred with pits and divots. Inside, his tables were full of in-process mosaics. Mosaics build images by assembling small bits of stone and glass fixed with mortar. But they’re not just gorgeous (and painstaking). They’re also as durable as any asphalt. So why not use them to fix up the street?

Bachor got to work.

Now, he’s in the midst of his fourth springtime pothole-filling campaign. He scouts for a likely spot, designs and creates a suitably sized piece, and returns—on a dry day, with some wet cement—to set the work. Then he posts on Instagram, letting his thousands of followers know where to find the latest in what has become an ongoing public art exhibition. A map on his website also plots locations—mainly west and north of downtown Chicago. Sometimes the first visitor to a newly installed mosaic gets a “goody bag” that Bachor has left nearby. (The bag’s contents are a surprise.)

Bachor’s fans have contributed to Kickstarter campaigns to fund this street art, which is otherwise not remunerative; it’s important to Bachor that his pothole mosaics cannot be purchased. Chicago officials are measured in their response. Bachor did not ask for permission before starting, and has never spoken to anyone in municipal services directly, but a city spokesman reminded Chicago Tribune readers that pothole-filling is best left to “professionals.” Some of Bachor’s efforts have been paved over by professional repairs.

Which doesn’t dim Bachor’s enthusiasm. Covered or not, a mosaic lasts. In fact, it was this endurance that first drew Bachor to the form.

On a revelatory trip to Europe in the late 1990s, he fell in love with ancient art and history and “really dorked out,” as he put it in a recent interview, with a self-taught course of research and travel. As he learned more, mosaics captured his imagination.

They’re “indestructible,” he explained. “On my first trip to Pompeii the guide was pointing out the floor mosaic and said, ‘That’s how the artist intended it to look’”—a couple of millennia ago. With mosaics, Bachor said, “you can create something that in theory could last for thousands of years.” Bachor returned to Pompeii in 2001 to volunteer at an archaeological dig. He later took a course in mosaic-making in Ravenna, Italy, before beginning to craft his own.

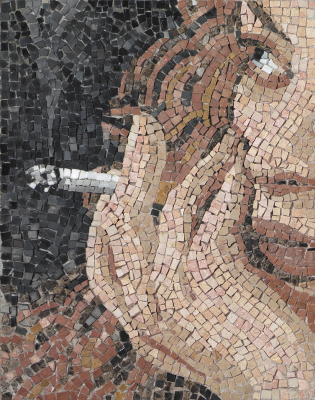

It’s a tough craft, Bachor said. You’re “confined by your materials” and it’s “hard to master.” But the challenge keeps him interested. How do you create something life-like using only hard, colored chips? Bachor orders smalti—tiny pieces of glass—made by Italian makers in Murano. They’re beautifully colored and expensive. So cost also limits his palate and options. But he’s committed to the old, enduring ways of making this old, enduring art.

While his techniques are traditional, Bachor’s images hardly seem antiquated. One set of pothole mosaics filled the streets with various bright flowers. Another used images of ice cream treats—cones, pops, bars. In his current series, which Bachor has titled “Pretty Trashed,” he plans to render various common pieces of garbage. So far, he’s done a crushed can and a parking ticket. His earlier career, as a graphic designer working often in advertising, influences his preference for bold colors and pop subjects—like his mosaic cereal box or coffee cup.

Though Bachor occasionally still works in design, most of his time now is taken up with mosaic projects. And not just the three dozen potholes that Bachor has mended in Chicago streets—plus the one he recently did in Detroit. He’s also completed commissions for a sports store, a subway station, and a kitchen, among other sites.

But the street pieces might be the purest representation of what he knows mosaics can do. Every mosaic is a “crazy time capsule,” Bachor said. It’s art of the past, filling a present need, and ready for a long future.

Send A Letter To the Editors