Finding Inner Peace Between Thin Black Lines

Agnes Martin’s Monochromatic Art Was Her Answer to Taoism’s Call for Austerity

Black is a strong color, and makes a powerful line. It is also elemental and austere—things that would have appealed particularly to artist Agnes Martin, who grew up in a Calvinist household in early 1900s Canada and was later influenced by Taoism and Zen Buddhism.

Black is a strong color, and makes a powerful line. It is also elemental and austere—things that would have appealed particularly to artist Agnes Martin, who grew up in a Calvinist household in early 1900s Canada and was later influenced by Taoism and Zen Buddhism.

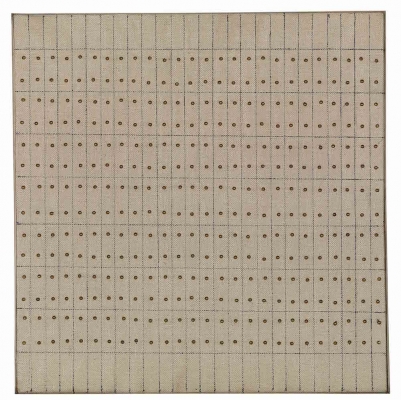

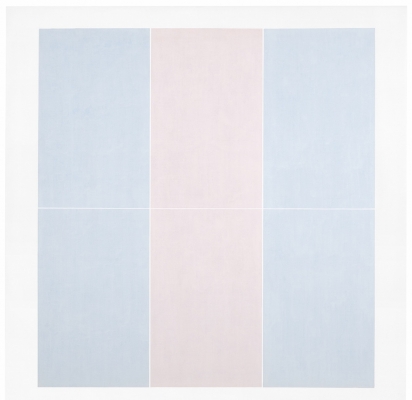

Martin is best known for her sublime abstract paintings of grids and lines, which at first glance may look like hand-drawn ledgers. Her early work from the 1950s and 1960s is mainly black, white, and earthen tones. In her long career, Martin did not solely rely on a monochromatic palette—she went into color, in a subdued way, in the 1970s—but she did return to it again and again.

After seeing “Agnes Martin,” the breathtaking retrospective of her work at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (through Sept. 11), a show that reminded me of the extraordinary beauty and discipline of her art practice, I wanted to explore some possible reasons why.

I found a clue in the opening lines of “The Untroubled Mind,” Martin’s thoughts from 1972, when she was returning to making art again after a hiatus of several years. These thoughts were recorded like a poem, in phrases, and read like a quiet but self-assured manifesto.

People think that painting is about color

It’s mostly composition

It’s composition that’s the whole thing.

The classic image—

Two late Tang dishes, one with a flower image

one empty. The empty form goes all the way to heaven.

The reference to the Tang dynasty of China is not accidental. In her writings and interviews, Martin often cited the strong influence of Asian philosophies. “My greatest spiritual inspiration came from the Chinese spiritual teachers, especially Lao Tzu,” she once said. Lao Tzu (now Laozi) has been generally accepted as author of the famous Tao Te Ching and founder of Taoism. In the same statement she also mentioned the influence of Buddhism, especially the Zen branch. Scholars can only conjecture as to where she picked up this knowledge, but it had a deep impact on her painting and her discipline.

Later in life Martin repeatedly spoke of the need for humility and ego-lessness, which is in sync with Taoism’s call for naturalness and simplicity. And as an adult, she meditated regularly, a Zen practice. She advocated looking inwards and of emptying the mind, tenets of Zen monks, some of whom became known for their monochrome painting. (She famously refused to accept awards or honorary degrees because, she said in an interview, “I don’t really think I’m responsible, so I don’t accept any awards.”)

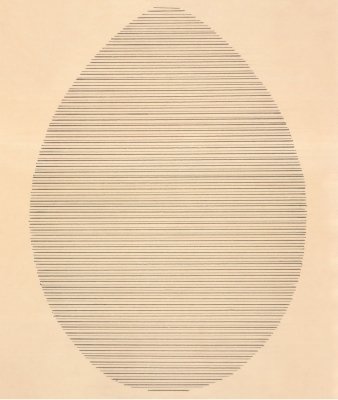

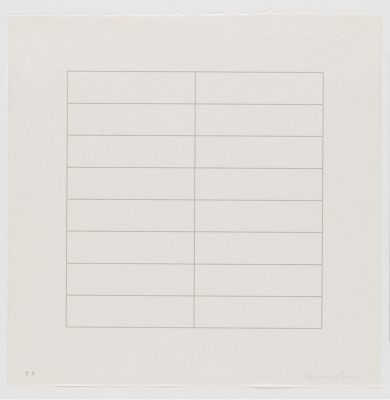

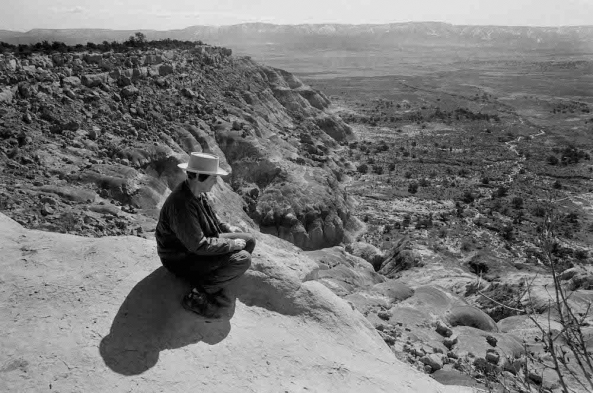

In the late 1950s, Martin had moved to New York City at the urging of her dealer, Betty Parsons. However, she left in 1967, packing up her things and going on a road trip for 18 months. She eventually settled in New Mexico, and reducing the distractions of daily life—diagnosed a paranoid schizophrenic, she had had more than one breakdown while in New York. In 1973, she announced her return to the art world with a series of 30 monochromatic screenprints, “On a Clear Day.” Each print is composed of thin black lines in grids or horizontal lines. “These prints express innocence of mind,” she wrote in 1979. “If you can go with them and hold your mind as empty and tranquil as they are and recognize your feelings at the same time you will realize your full response to this work.”

In this latter period, she often said that her work was about happiness, perhaps her way of describing inner peace. I find that looking at her work demands focus and shutting out distractions. Your eye swims around the soft lines, simple forms, and translucent pastel colors, until your mind finally comes to rest. The newly re-opened San Francisco Museum of Modern Art very deliberately sets her work apart, presenting seven of her paintings in an octagonal room, with seating in the middle, a kind of Martin “chapel” which facilitates quiet and contemplation.

Basic black-and-white drawings and paintings show composition most clearly. She must also have appreciated Chinese brush painting, which is traditionally done with a soot-based ink with highly flexible brushes. Arne Glimcher, her longtime dealer and friend, recalls in Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances that in the 1980s he had sent her a book on such work. On his next visit he saw “a series of grey canvases, each with diluted India ink washes under pencil grids, some with horizontal lines and others with vertical and horizontal lines.” Martin said to him, “Imagine yourself one of those little Chinese men in a brush painting and get into those boxes and look around.”

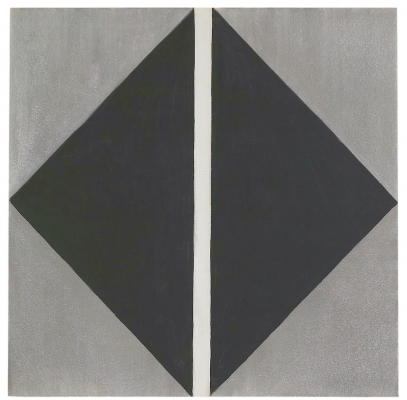

She did take up color—pastel washes worked into bars and grids, perhaps a reflection of the New Mexico sky and landscape. Still, I find it interesting that towards the end of her life she went back to the monochromatic palette in such important works as “Homage to Life” and “The Sea,” both from 2003, a year before she died.

In the latter, the black is intense, and the composition insistent—it is mostly black, with thin white horizontal lines pulsing across the large, 5-foot-by-5-foot canvas. Something in the slight irregularity of the white lines gives them a sense of movement, of surging rhythm, as of ocean waves that can be ever changing and yet patterned at the same time. It’s true, Martin had long avoided representing the outside world, and was more concerned with the truth within. Still, I do not think she could turn her back to the world completely—she just had to represent the elemental in her own way.

Send A Letter To the Editors