Since the military coup of 2006, the Thai government has prosecuted hundreds of Thai citizens who made comments about the monarchy, under the authority of Thailand’s lèse-majesté laws. The sentences have been stunning, with people forced to serve 10, 30, or even 60 years in prison for “crimes” that generally are nothing more than a few sentences on Facebook.

Under the lèse majesté laws anyone can be charged with the crime of disrespecting the king, queen, or any heir to the throne. The current monarchy-backed military junta has used these laws to protect members of the King’s families, including, absurdly, their pets. Late last year, a young man was arrested after he posted a meme that mocked the king’s dog on a satirical Facebook page. Because of his joke, he now faces up to 37 years in prison.

These prosecutions indicate a problem far older than social media: Thailand’s constitution is designed to protect the king above everything else, including justice. Today, the first chapter of the constitution reads, “The King shall be enthroned in a position of revered worship and shall not be violated. No person shall expose the King to any sort of accusation or action.”

Because of this, the whole kingdom of Thailand is wary of honest conversation about the monarchy—and about the army generals who have frequently attempted to manipulate our country’s democratic system (nominally in place since a 1932 coup overturning the absolute monarchy of King Bhumibol’s uncle). This is quite a chilling effect, as the royals’ first coup to overthrow the constitutional government and regain power was attempted after democracy failed in 1933. The last, to date, occurred in 2014. Each time the king regains power, none of the coups’ leaders are ever brought before a court of justice.

To understand Thailand’s cycle of “coup, uprising, crackdown, election, coup” is to understand the relationship King Bhumibol—the world’s longest reigning monarch, having come to power in 1946—has with coups. By my count, approximately 10 coups have been staged for the king between 1947 and 2014. Each time, the palace’s Privy Council and other powerful actors have been able to generate enough military power to retain control for themselves and the civil servants that constitute this country’s elite.

This preoccupation with meddling in election results and quashing uprisings has left the majority of Thais with a subpar quality of life.

Young King Bhumibol.

I was born in 1966 in a rice-growing village 100 kilometers from Bangkok, Thailand’s capital. Because of its location, births were overseen by a midwife, rather than a medical doctor. As a youth, I was among the approximately 37 percent of Thai people suffering from thalassemia, a genetic blood disorder that degrades the carrier’s blood cells and can lead to anemia. I often think about how lucky I am to have survived my childhood sickness under the spotty care of the veteran medics and nurse’s assistants whom we called “doctors.”

This inferior health care was the norm for more than half of Thailand until the 1990s. If someone in the family needed serious medical attention, it meant selling anything you could to pay the medical bills and/or appealing to civil servants, who often seemed to only respond to bribes of food, gifts, or cash. (For this reason, the most secure life you can have in Thailand is to be a civil servant.)

Thus the less-secure classes cherished free universal health care when they experienced it for the first time in 2002, after it was implemented by Thaksin Shinawatra’s newly elected Thai Rak Thai party. When this happened, the whole country realized that bribing or personally knowing a civil servant was no longer the only option for getting reliable access to healthcare.

I like to think that the plan was implemented as a result of the mobilization of rural people who spurred the Thai Rak Thai party to power. However, the party dissolved after the monarchy regained control via yet another coup in 2006. This coup led to Shinawatra’s exile and many of his supporters being banned from practicing politics for years.

But dissatisfaction with the monarchy’s status quo, mainly among rural and lower-class Thais, remained, and led to massive demonstrations in 2010. Protestors from the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (commonly known as “Red Shirts”) took to the Bangkok streets in April and May of that year, and were met by tens of thousands of Royal Thai Armed Forces who opened fire on crowds, killing 100 people and leaving close to 2,000 injured. Shocked rural and urban Thais might not have supported Shinawatra’s political party—I myself do not support it—but the massacre alerted them to the brutality and selfishness displayed by the elite establishment and its protected class of civil servants.

The crackdown in May 2010 was yet another catalyst for many political activists to install democratic principles in Thailand. I answered my calling a few years before this, when I self-published an essay titled “Why I Don’t Love the King” and decided to live in exile outside Thailand. Today, I’m in Finland, but continue write on the “unspeakable” (under lèse-majesté) issues still affecting Thailand.

For instance, much of the national tax revenue is being funneled towards the nation’s elite. The budget allocation to the palaces has increased greatly since King Bhumibol came to power in 1946. And since the 2006 coup, the purpose of the national budget has been to support the development of the capital city of Bangkok and to look after the two million civil servants, military, and police, all in the name of protecting and honoring the King. This has worked out well for King Bhumibol; for almost a decade Forbes has ranked him as the world’s richest monarch, with a net worth of $30 billion.

Meanwhile, rural politicians fight amongst themselves over budget scraps, which they use to secure their families’ fortunes. The members of parliament in my hometown province, Suphanburi, have been passing positions between networks of family members for as long as I can remember.

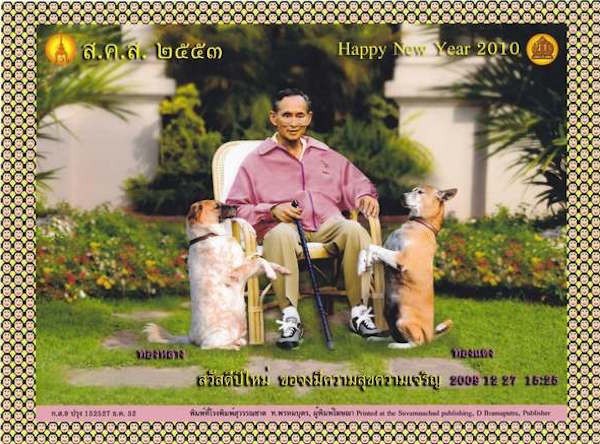

2010 New Years Card for the Thai people, given by His Majesty the King of Thailand, King Bhumibol Adulyadej.

Growing up, we would hear things like “by the time the commission fees have been divided up, the money remaining for the construction of roads will only be around 20 percent.” On top of that, the prices for building materials such as brick, stone, and cement are greatly inflated, to the point where one of the Crown Property Bureau’s largest sources of income is from cement sales. As a result, Thailand’s road projects often take forever.

These issues have not spurred Thailand’s remaining political parties to action. No political party explicitly opposed the coups that occurred in 2006 and 2014, and they never felt the need to mobilize so that they could tell the military to go home. Party leaders resisted action so that they could protect their own families and businesses.

And so the current Thai junta survives, even though junta members have done nothing to endear themselves to the public, choosing instead to strengthen their ties to the monarchy. In March 2015, under the orders of Prayuth Chan-o-cha, a retired army general who leads Thailand’s National Council for Peace and Order, Article 44 was added to Thailand’s interim constitution, granting the junta unlimited legal power whenever the King feels threatened.

In return, the Privy Council, the body that advises the King, as well as other palace insiders, pushed out propaganda arguing that Thailand is not ready for democracy and is better off under the protection of 1,400 generals and 400,000 soldiers.

King Bhumibol seems to fear that he cannot keep the hearts of all Thai people submissive, and that they will one day rise up to eliminate the monarchy once and for all. And yet, because of his increasing reliance on lèse-majesté, many people outside of Thailand believe the king is universally beloved, and have no idea that there might be a different reality than the anachronistic story pushed by the palace. Indeed, the harsh lèse-majesté sentences have helped encourage that fantasy within the country as well.

There is a saying among the critical voices in Thailand that Thai people are living under a coconut shell, believing that Thailand is the most fantastic nation in the world, that Thai people are the sweetest human beings, and that the Thai king is the king of all kings. But outside of the coconut shell, the view is much darker.

*An earlier version misstated the year of the 2010 demonstrations.

Send A Letter To the Editors