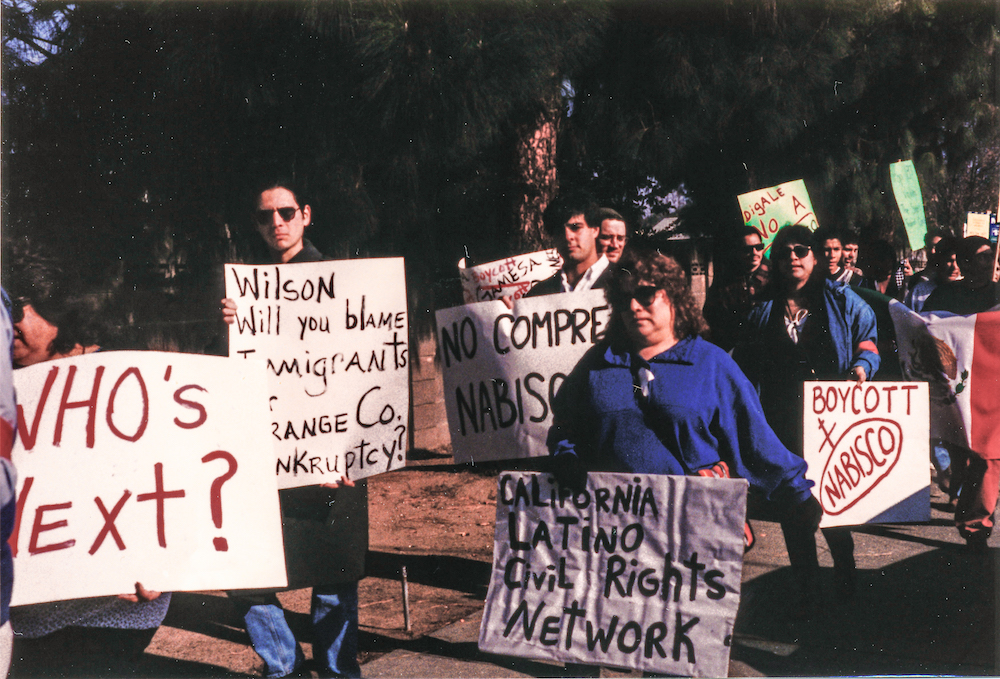

March Against Prop 187 in Fresno, California, 1994. Photo courtesy of David Prasad/Flickr.

It’s often said that California is just like America, only sooner. We confront the same issues as the rest of the nation, just earlier. Perhaps no issue exemplifies that sentiment better than immigration.

The things Donald Trump is saying about immigrants sound very familiar to those of us Californians who have been involved with immigration issues for the better part of our adult lives. Substitute former California Governor “Pete Wilson” for “Donald Trump” as the author of some of these quotes, and you could convince me that we are living in 1994 California, not 2017 America. We just got there sooner.

In 1994, California was still mired in recession, lagging behind the rest of the country in what would become the remarkable economic recovery of the 1990s. Instead of focusing on housing, job creation, higher education, or retraining workers for the burgeoning information economy, some prominent Republicans decided it was easier to blame “illegal” immigrants, despite persistent statistics that immigrants use fewer public services than native-born residents. And so, Proposition 187 was placed on the ballot.

Arriving at a time when Latinos were beginning to reach critical mass in California, Prop 187 was almost perfectly (if unintentionally) designed to galvanize a generation of activists—which is exactly what it did.

For those too young to remember, Prop 187 would have barred all undocumented immigrants from using public health care facilities, public education, and many other publicly funded services. Yes, you read that right: It would have barred hospitals, schools, and other vital services from people who needed them. Worse, it required various public officials in public agencies to report people whom they “suspected” were not documented to authorities. Essentially, not only would it have kicked millions of Latinos out of hospitals, schools, and other public places, but it would also have created a witch-hunt atmosphere, allowing for people to be turned in for simply “seeming” illegal.

I was 27 years old in 1994, working at a nonprofit helping immigrants navigate the difficulties of life in Los Angeles, alongside some friends including Gilbert Cedillo and Kevin de Léon. We immediately saw this for what it was: an attempt to lay the blame for persistent economic uncertainty at the feet of a growing minority—the “Other.” So, we did what we were good at: We organized people; we rallied; and we tried to show that the Latino population couldn’t be taken for granted.

What surprised Pete Wilson and his Republican colleagues was that their plan to push people to the margins of society achieved the exact opposite. People were so outraged, so motivated, and so galvanized by this blatant attack on their American Dream that they moved out of the shadows and pledged to show the world that they were real people with real hopes and real aspirations.

To prove that, we organized two marches. The first, on February 28, 1994 in Los Angeles, was 20,000 strong; many of the attendees were people who, just a few short months earlier, were nervous about attending parents’ night at their child’s school for fear of running into authorities who would deport them. But at the march, they were fighting for their rights in front of television cameras.

On October 16, just a couple of weeks before the election, we staged another march, from Boyle Heights to City Hall. And this time, it wasn’t just Latinos. It was religious and civic and elected and community leaders, marching in solidarity with us. And this time, we were 100,000 people—standing up for the American Dream, and standing up to say that American opportunity isn’t just for the few able to get through an arcane, Byzantine, broken immigration system. It’s for everyone.

I’ll never forget one telling moment: When that march was over, people didn’t just go home. They took a few minutes to pick up the trash around them. Just as we were demanding not to be taken for granted, we were not taking our community and our country for granted. We were demanding respect and dignity, and were committed to showing respect and dignity. We wanted to leave our community cleaner than we found it.

We lost the battle: Prop 187 passed, though it was later deemed unconstitutional and was never implemented. In retrospect, not all of our tactics were as politically astute as they should have been, but we were passionate, and we were angry.

With the benefit of two decades of hindsight it’s obvious that Prop 187 planted the seed out of which Latino activism and political power began to grow. I was eventually elected to the Assembly and became the longest serving Speaker since Willie Brown. Gil Cedillo was elected to the Assembly, Senate, and now serves on the Los Angeles City Council, championing immigrant rights during his entire career. My good friend Kevin de Léon is the current President Pro Tem of the State Senate. Many other Latino political pioneers—from the legislator Richard Polanco, to former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, to the late labor chief Miguel Contreras—came of age during the fight over 187.

And, more broadly, because of Republican Governor Pete Wilson’s high-profile support for 187, Latinos were cemented firmly to the Democratic Party during a time when the Latino vote was still up for grabs. In 1994, Latinos were 28 percent of the population, but only eight percent of the electorate. By 2016, Latinos were 38 percent of the population and 31 percent of the electorate. For anybody wondering why Republicans can no longer win statewide offices in California, look no further than the legacy of this blatant attempt to disenfranchise Latinos.

As I’ve listened to Donald Trump’s rhetoric about immigrants in general and Latinos in particular, I hear what many California politicians were saying 23 years ago. Like them, Trump is appealing to people with very real economic concerns by scapegoating an entire class of people who are not the cause of it. Just as 187’s backers avoided the very real and very difficult challenges of adapting to a new kind of economy, Trump is evoking a past that never really existed as somehow “great again.” He is also ignoring data as he pursues demagoguery. He is exploiting fears over safety, ignoring the fact that the vast majority of terrorist acts now—and more localized crimes then—are perpetrated by native-born residents.

This approach is cheap; it is disingenuous; it is simplistic; and, worst of all, it doesn’t actually solve anything. We could build a wall on the Mexican border tomorrow AND ban all Muslims from entering the country, and none of the issues that Donald Trump is claiming to solve, or protect us from, would change or be resolved. Just like turning California into some sort of heartless police state in the ‘90s wouldn’t have helped an unemployed oil worker in the Central Valley get a job.

Trump’s rhetoric, and the 187 rhetoric before it, share one very nasty characteristic: both are deeply pessimistic. California’s progress since 1994 shows that the best way to adjust to economic change is by confronting challenges head-on. Our state has shown that a tough-minded, optimistic and inclusive spirit can create more prosperity.

So, what does the Trump era mean for immigrant L.A.? First, we have to remember that days that seem dark now can turn much brighter tomorrow. If we stay focused. If we stay organized. If we stand in solidarity. And if we stay out of the shadows.

Send A Letter To the Editors