Are You Cursed If You Steal Rocks From the Petrified Forest?

A Photographer Ponders Beauty, Truth, and the Guilt of Visitors Who Pilfer Souvenirs From the Arizona National Park

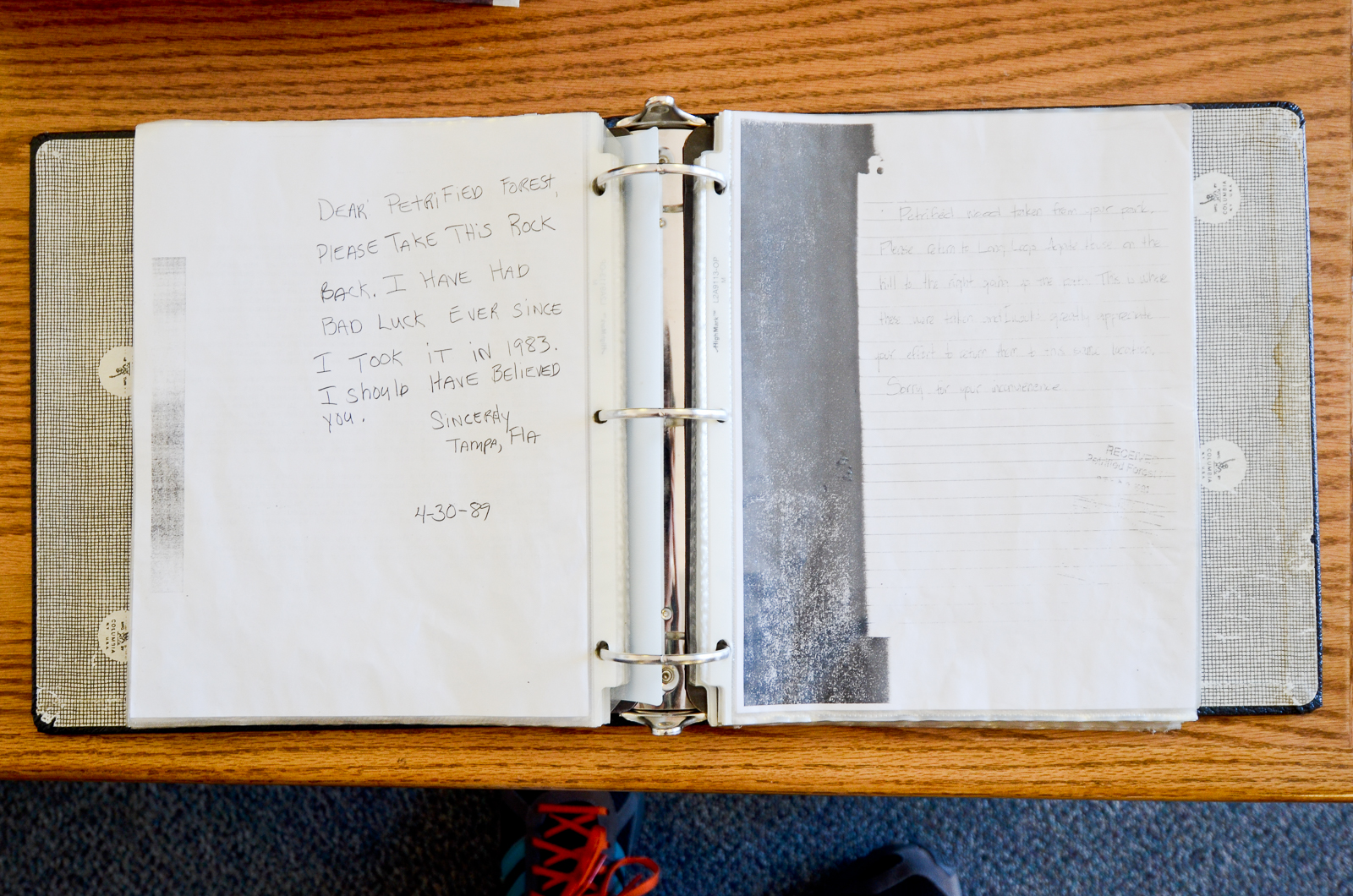

In 2011, I was traveling in Arizona photographing meteorites and the misidentified meteorites known as “meteor-wrongs.” My work with the meteor-wrongs went quicker than expected and my wife and I saw the Petrified Forest National Park wasn’t far away, so we took a day trip out that way. And that’s where I stumbled onto a display of these letters, written by people who’d taken petrified rocks from the park but then wanted to send them back.

I was blown away by the letters. They were at turns heartbreaking and hilarious. People want to do good, and you can see them wrestling with the idea that they’re trying to undo what they did. Additionally, there are stories upon stories of bad luck—from a plane crash near the park to car troubles, and even illness—all attributed to the pilfered stones.

But the ultimate irony is that the returned material can’t be put back in its original resting place. To do so would be to spoil those sites for research purposes, so they end up in the ‘conscience pile.’ The conscience pile is a kind of no man’s land—a space designed to be separate from the park, within the park. Rangers that I spoke with didn’t know when the pile was started and they have no plans for its future—so the rocks continue to pile up.

We spent a couple days handling the rocks and making photographs. We also made a temporary monument—a sculpture assembled using these stones—as a way of thinking of them not just as individual rocks but as a collection. You can find chunks of concrete, shards of sandstone, and pieces of coal slag among the petrified wood. The thing the conscience pile rocks have in common is that they’ve all been picked up and moved by people. It’s an interesting collection that has a lot of weight to it, literally and metaphorically.

Petrified wood itself is very magnetic; it’s beautiful, uncanny really, because it looks like wood, but it’s really heavy. I can see why, for a lot of people, it becomes this really enviable sort of thing to take home. After my second trip to the park, I wound up purchasing some random bits on eBay because I wanted to have some petrified wood to call my own. But it wasn’t ultimately satisfying in the same way. It didn’t fill that void of wanting to be connected with that specific place and time. So I can relate to people’s desire to want, to have, and to hold in their hands something that connects them to that landscape.

The stone that is photographed on a map came from my first visit. I was chatting with a ranger and a woman walked in. She was returning the item after having picked it up years ago, and she said something along the lines of, “Hey, I took this, and I just want the park to have it back.” It’s just this very small piece, probably two inches by one inch. I didn’t talk to her; I haven’t really had any contact with the people who have returned this wood and written these letters. I think there’s a little bit of shame wrapped around it. But I appreciated her returning the thing in person.

The funny thing about returning a rock is that it has to be done in person or through the mail. So you get these boxes that are completely tattered, because they’ve been flown around the world, or have been driven by truck across the country, and you get these handwritten, hand-typed, or printed-out letters. You can’t just fire up an email or make a social media post about it, so it has a more intimate appeal. And it becomes kind of confessional in that way.

I photographed the rocks on a white background. I really just wanted to see them set apart from their context as a way of appreciating their beauty and the intricacy. These things are really, really beautiful to behold, so the photos are kind of a way of recalling that experience of wanting to pick one of them up and own it. In many of the photographs, scale is intentionally left to the imagination. It’s hard to tell how big these rocks are—some are a couple feet across while others may be the size of a pea. I like leaving it to the viewer to fill in some of those details.

We tried to get a sort of random sampling, pulling out pieces of gorgeous petrified wood that felt that they could have come from the park and other scruffy bits that likely didn’t—a kind of overview of what the actual material looks like when you’re standing there at the pile. Who knows why they were picked? Someone was attracted to the one that looked like little pink salt crystals, someone else was attracted to the one that looked like a tree branch, someone else was attracted to the one they had to put in the trunk of their car because it weighed 60 or 80 pounds.

I love that they’re all so different. Everyone has a different idea of what would make a good souvenir.

I don’t know how many letter writers acknowledged it at the time but to me they’re sort of saying: Wait, this wasn’t mine to disturb, to have, or to own. That is a really powerful realization. Hopefully it leads to a larger dialogue on sustainability and how we can be better citizens of global ecological systems. I can’t help but think that people are engaging those questions when they think about this one little rock they picked up.

Send A Letter To the Editors