Jennifer Sinclair, sister of Army Captain Peter Sinclair, remembered her brother before the war as fit, funny, gregarious, and “the life of the party,” she told the audience at the Hammer Museum. Peter had served in the Gulf War and as a Los Angeles police officer before being deployed to Iraq.

But Jennifer received a troubling email in early 2005 from Peter, who was suffering from a severe spine injury but nonetheless insisted on staying in Iraq to lead his men. “I’m a mess, Jen,” it read. “I’m not thinking clearly. I can’t sleep and I’m very worried.”

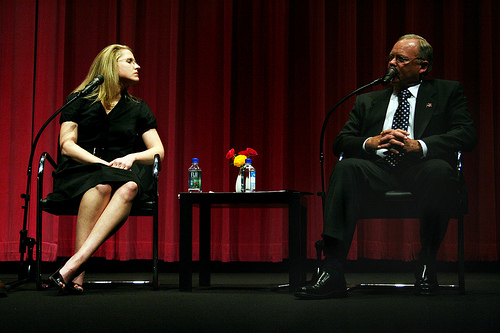

Jennifer joined Army Major Gen. (Retired) Paul E. Mock, David Webb, chief of environmental and military medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center Long Beach, and moderator and Los Angeles Times veterans affairs reporter Jia-Rui Chong to discuss the aftermath of Peter’s devastating injury. His was a tragic case of what can happen when veterans come home needing serious care.

Diagnosis

Sinclair described the difficulties Peter faced, first in Puerto Rico, where he couldn’t receive the serious care he needed, and then in the continental U.S. Only through the dedicated effort of his family did Peter manage to see a doctor at UCLA – before which he was assigned to a private physician who, Sinclair said, “mislabeled the vertebrae on the X-ray.” Peter worked simultaneously with private and Veterans Administration’ therapists for his mental health – he had witnessed a particularly brutal suicide bombing in which many children had died. But he had difficulty coordinating treatments and receiving full care. “There is no one system for care,” Sinclair said. “It is almost impossible to navigate.”

Sinclair described the difficulties Peter faced, first in Puerto Rico, where he couldn’t receive the serious care he needed, and then in the continental U.S. Only through the dedicated effort of his family did Peter manage to see a doctor at UCLA – before which he was assigned to a private physician who, Sinclair said, “mislabeled the vertebrae on the X-ray.” Peter worked simultaneously with private and Veterans Administration’ therapists for his mental health – he had witnessed a particularly brutal suicide bombing in which many children had died. But he had difficulty coordinating treatments and receiving full care. “There is no one system for care,” Sinclair said. “It is almost impossible to navigate.”

Mock, who met Peter and worked on his case, and Webb, who also helped care for Peter, both agreed that divisions in the veterans’ healthcare system can complicate care. Mock said that active duty soldiers and reservists have separate records systems, but while a reservist is at war, he or she becomes part of the active duty system. Peter remained in the active duty system instead of returning to the reserve system at home. “They literally lost track of him,” Chong said. Furthermore, Webb noted, while the Veterans Administration has a strong computerized medical records system, the army has a separate computer and paper system, which sometimes isn’t easy to access. Sinclair said she had to track down Peter’s army medical records herself, since the army didn’t provide them to the Veterans Administration.

Complications

Another divide, Webb noted, is in care rather than record-keeping: many soldiers have several diagnoses that need treatment, and too often, such treatment isn’t provided holistically. As Sinclair said starkly, noting that injuries come with mental health problems, “You get blown up. You’ve experienced trauma. It stays with you mentally.” Peter, she said, was turned away for mental health care because he had physical ailments, and had difficulty treating his physical ailments because of his pill regimen for mental health.

Another divide, Webb noted, is in care rather than record-keeping: many soldiers have several diagnoses that need treatment, and too often, such treatment isn’t provided holistically. As Sinclair said starkly, noting that injuries come with mental health problems, “You get blown up. You’ve experienced trauma. It stays with you mentally.” Peter, she said, was turned away for mental health care because he had physical ailments, and had difficulty treating his physical ailments because of his pill regimen for mental health.

Soldiers often come in with what Webb called the three P’s: pain, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and post-concussive disorder, also called traumatic brain injury (TBI). For PTSD, Mock noted, more soldiers are open about asking for help, though many still do not, and families are trained to look for symptoms. (Though Sinclair pointed out that some in the Army denied that Peter had PTSD, even though he was later diagnosed with it.) As for brain injuries, Webb said, “TBI is the signature injury of the war in Iraq” because of blows from improvised explosive devices. And mild TBI, as Webb noted during Q&A, is sometimes overlooked or mistaken for mere bad behavior. The combination of ailments is very hard to treat because each aggravates the others, Webb said.

Still, Webb and Mock noted that the system is better today than it was for Vietnam veterans, who were not treated specifically after their deployment and were, as Webb said, “thrown in the general mix of World War II and World War I veterans with high blood pressure and diabetes.” Today, soldiers are thoroughly screened after their deployments, Webb said, and computerized records help clinicians keep track of treatments. Particular hospitals, like the Tampa VA, are also instituting joint clinics to treat ailments that hit together.

Still, Webb and Mock noted that the system is better today than it was for Vietnam veterans, who were not treated specifically after their deployment and were, as Webb said, “thrown in the general mix of World War II and World War I veterans with high blood pressure and diabetes.” Today, soldiers are thoroughly screened after their deployments, Webb said, and computerized records help clinicians keep track of treatments. Particular hospitals, like the Tampa VA, are also instituting joint clinics to treat ailments that hit together.

Despite the efforts, treating such complex cases is still “very difficult,” Webb said. “How [various medications] work with people with multiple problems is unknown. One has to try things and watch the patient very carefully to see what works.”

Prescriptions

One of the most common problems for returning veterans is overmedication. Sinclair said that at one point, her brother was taking 15 medications while suffering short-term memory loss from PTSD, leaving him unable to track his schedule of medicine. “When you send [a soldier] home or put him in his room on base you provide him with very limited access to mental care,” she said. “It’s not going to go well.”

Despite his family’s efforts, Peter died of an accidental overdose of morphine. His family did not know he had been put on morphine, prescribed to him by a resident, along with valium and codeine. When he received the morphine, Peter had liver damage from medication and had been off opioids for months. Opioids, as Webb noted, have gone from being rarely used to overused, as doctors began to believe pain is under-treated.

Despite his family’s efforts, Peter died of an accidental overdose of morphine. His family did not know he had been put on morphine, prescribed to him by a resident, along with valium and codeine. When he received the morphine, Peter had liver damage from medication and had been off opioids for months. Opioids, as Webb noted, have gone from being rarely used to overused, as doctors began to believe pain is under-treated.

Sinclair suggested a number of things that might have prevented her brother’s death, and that could still save other veterans: closer monitoring of patients with chronic pain and PTSD; stronger guidelines for prescribing pain medication; proper testing and screening before prescribing; and strong monitoring throughout. “We need significant system change within the Army and the VA,” she said. “Please don’t ignore these gentlemen and women who stand up and say ‘I have a problem.’”

Mock and Webb echoed her sentiments, noting efforts already underway at the VA under President Barack Obama and Veterans Affairs Secretary Eric Shinseki. However, as Mock said, “It’s a complex problem. There’s no bumper sticker for it.”

Watch the video here.

See more photos here.

*Photos by Aaron Salcido.

Send A Letter To the Editors