Charles Darwin lived and worked in what Phillip Prodger calls “a time of profound transition in visual culture.” The relatively new technology of photography was becoming a tool of scientific inquiry, and Darwin, Prodger argues in Darwin’s Camera: Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution, used it well, changing the way photographs were seen and used. The father of evolutionary theory was exacting in his choice of images and engravings for his groundbreaking work in, among other books, The Descent of Men, and Selection in Relation to Sex and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Below, Prodger’s descriptions of selected photographs that Darwin used in these two works, or as inspiration. (Click on the photos to enlarge, click on them again to return to the post.)

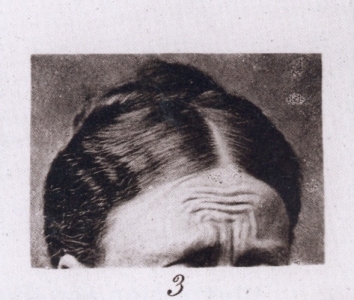

Her identity is obscured – the shape of her face, her demeanor, manner of dress, and location; no reliable judgments can be made about her class, age, or occupation. Darwin described the picture as “the forehead of a young lady who has the power in an unusual degree of voluntarily acting on the requisite muscles.” It was intended to illustrate the horseshoe-shaped furrows visible on the forehead in acute states of misery, the result of certain muscle groups contracting in opposition to one another. He withheld the rest of the picture, he explained, because the unaltered image was not convincing…. Darwin wanted his pictures to have semantic force: to embody a general truth about human or animal physiology. The disembodied forehead in Expression takes on the meaning of all foreheads, showing everything Darwin wanted us to learn from a single example…. Pictures may also have emotional associations. This is one reason Darwin cropped the forehead picture as severely as he did. He was concerned that if readers saw the rest of it, they might feel pity or humor, which were unwanted associations that detracted from his message.

The most popular treatise on expression [prior to the publication of Darwin’s] was published by the Swiss theologian Johann Caspar Lavater in 1772…. The range of illustrations in Fragments was impressive. Included were pictures comparing humans and animals, silhouettes, catalogues of lips, noses, and other features, portraits of eminent personages, analytical diagrams, and even genre scenes. Most took the form of people dressed in contemporary costume. Ethnicity was strongly emphasized in the work, and manner of dress…. At the end of the book, Lavater demonstrated that through the judicious addition of lines, an artist could transform a simple drawing of an animal into a human portrait. He did not intend to suggest that a frog could transform itself into a man exactly, but… his illustrations evoked proto-evolutionary themes.

Just as Darwin’s rivals were seeking to enlist photography in their campaign against the theory of evolution by natural selection, his allies were preparing their own pro-Darwinian photographic campaign. In England, Thomas Henry Huxley, Darwin’s staunch ally, had become interested in photographic anthropometry, that is, the application of photography to the mathematical analysis of anthropological specimens…. In 1868, Huxley probably first saw photographs being presented by his ethnologist colleagues, a packet of photographs by the Ellis Studio of a Burmese family with apelike hair all over their bodies…. It is now known that these accounts are consistent with the symptoms of a rare genetic abnormality known as congenital generalized hypertrichosis. However, there is little evidence that Huxley took such accounts seriously. Darwin, too, seems to have been uncertain what to make of them. In Descent of Man he claimed that the thin layer of short hairs that cover the bodies of humans to varying degrees is undoubtedly “the rudiments of the uniform hairy coat of the lower animals.”

In “Horror and Agony”, the last illustration in Expression, the subject looks directly at the reader. In Expression, Darwin praised Duchenne’s photographs. However, he did not embrace them fully. Some of the pictures, such as those of horror and agony, could not be mistaken for anything else. Others were more ambiguous. Mindful that these might be misinterpreted, Darwin showed them to friends and colleagues and asked them to judge the expression portrayed…. Duchenne’s electrical experiments gave the human face the status of an appliance; expressions were just so many bundles of muscles to be tweaked and stimulated at the will of an experimenter. He was principally an anatomist, concerned with the physiology of facial mechanisms, and did not attempt to explain the origins of expression as Darwin did.

In Descent of Man, Darwin argued that the human body exhibits residual features of animal progenitors. Among these was a slight inward indentation of the outer ear, “a little blunt point, projecting from the inwardly folded margin, or helix,” which is visible in certain individuals. This, Darwin believed, was a vestigial form of the pointed ears of apes and other simians. Since he proposed that humans have evolved from apes, he reasoned that human ears must have evolved from ape ears. The slight inward protrusion of some human ears is all that remains of the pronounced point evident in apes.

…Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton invoked Darwinian theory to try to explain differences between the races, and also like Darwin, he was interested in what photography could reveal about human nature. However, his slant represented a retrenchment of sorts, because he played off ideas popularized by physiognomists some hundred years earlier. Galton believed character is written in personal appearance and that people with similar inclinations share common facial features. This, he maintained, could be demonstrated through photography….

In his book, Inquiries into the Human Faculty (1883), Galton examined members of the same family, officers and privates in the Royal Engineers, criminals, and diseased people with and without tuberculosis. He gathered portraits of individuals in each category and then combined them in composite prints in an attempt to discover ideal types. Galton photographed prints to get negatives, which he then sandwiched one on top of the other and printed on a single sheet of photographic paper in perfect registration. The cumulative effect of superimposing so many exposures was the deemphasis of outlier characteristics and the enhancement of commonalities.

*All photographs courtesy the Collection of Phillip Prodger.

*Photo on homepage of the Darwin Arch in the Galapagos courtesy PTorrodellas.

Send A Letter To the Editors