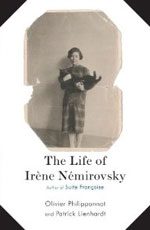

The Life of Irene Nemirovsky: 1903-1942

by Olivier Philipponat and Patrick Lienhardt

–Reviewed by Shahnaz Habib

The novelist Irene Nemirovsky did not merely live through the early 20th century. Her life was a consequence of its cataclysms. Growing up in Ukraine in a privileged family, she came of age as an exile in France because of the Russian Revolution. Driven out of France after the German invasion, she died at Auschwitz in 1942. Nemirovsky’s incomplete novel series Suite Française, in which she aimed to show life in France under Nazi occupation, bears witness to this storied, varied life. And in a new biography, The Life of Irene Nemirovsky, French writers Olivier Philipponat and Parick Lienhardt spotlight the drama, at once public and private.

The novelist Irene Nemirovsky did not merely live through the early 20th century. Her life was a consequence of its cataclysms. Growing up in Ukraine in a privileged family, she came of age as an exile in France because of the Russian Revolution. Driven out of France after the German invasion, she died at Auschwitz in 1942. Nemirovsky’s incomplete novel series Suite Française, in which she aimed to show life in France under Nazi occupation, bears witness to this storied, varied life. And in a new biography, The Life of Irene Nemirovsky, French writers Olivier Philipponat and Parick Lienhardt spotlight the drama, at once public and private.

Beginning in Kiev, Ukraine, the biographers follow Nemirovsky’s highs and lows, first from the perspective of a wealthy, cosmopolitan Russian banking family (shopping in Paris, carnival in Nice), and then from that of an émigré fleeing persecution – a fortified house in Moscow, a sparse Finnish border town, the shocking splendor of Stockholm, and finally Paris again. The city is colorful, jubilant after the war, a refuge for exiles, where “you might hear the popular cry ‘Izvoshchik’ normally used to hail one of the three thousand Russian taxi drivers in the capital.”

It is in Paris that Nemirovsky becomes a literary sensation, conveying, as the critic Robert Brassilach put it, “the vast Russian melancholy in a form that is French.” In Paris, where her father dies after frittering away his fortune, Nemirovsky marries, raises her children, and becomes the primary breadwinner of her household. And finally, it is Paris that Nemirovsky flees after the Nazis take the city – only to be arrested, separated from her family, and eventually sent to Auschwitz.

Through meticulous research into Nermirovsky’s journals, letters and drafts, which surfaced in 2005, Philipponat and Lienhardt have succeeded in fleshing out this enigmatic artist’s life and persona. Nemirovsky was a disciplined writer who took her vocation seriously, paying the bills with short stories and using her novels to explore broad social themes and in-depth characterization. Her most celebrated work is Suite Française, which she planned as a series of five historical novels about the very history unfolding around her. She was killed before she could complete this feat of social observation, leaving only two novels and a bare outline for a third.

One of the great delights of this biography is the scrupulousness with which the biographers trace the links between Nemirovsky’s life and her fiction. While the autobiographical elements in David Golder – in which a self-made Russian-Jewish banker ends his life in ruin and exile – are explicit, it takes a literary detective to connect the dots between the Basque countryside where Nemirovsky spent her summers and the beach in Le Maltendu where a society woman falls in love with a penniless worker.

Throughout the book, Philipponat and Lienhardt also confront the allegation that Nemirovsky’s writings contained anti-Semitic elements – her characters are often interpreted as caricatures of the Jewish bourgeoisie. The biographers provide valuable context by tracing different themes in Nemirovsky’s writings on a timeline. For instance, Nemirovsky’s complicated relationship with her mother, in her own terms, her “exquisite hatred” for her mother, transferred itself into much of her early autobiographical fiction. But draft notes for a late-period short story, “Fraternite” show that Nemirovsky struggled to depict “that race that had not dropped their guard knowing that the roof belonged to them, that their house belonged to them, like a French peasant, but that everything could be taken back.”

A biographer’s job is a precarious balancing act – between describing the world that the subject lives in, and describing the subject against the backdrop of that world. Too often, Nemirovsky’s biographers err on the side of privileging her subjectivity. We see her mother and her marriage and France through Nemirovsky’s eyes. It is almost as if Nemirovsky’s “exquisite hatred” for her mother transferred itself to the biographers: her mother is referred to variously as a “fickle and contemptuous woman” and “‘as lustful and mendacious as she was venal’. Surely the facts of Nemirovsky’s life and the fiction she wrote are eloquent enough without such commentary. And yet, this is a fine flaw for a biography. To see Irene Nemirovsky’s life through her eyes is a gift in itself for readers who have been tantalized by too little, too late.

Further Reading: Suite Française by Irene Nemirovsky and Irene Nemirovsky: Her Life And Works

by Jonathan Weiss

Shahnaz Habib is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn.

*Photo courtesy Pedro Simoes.

Send A Letter To the Editors